22 January 2018

Teens living in suburban areas on the outskirts of Île-de-France often seem to be victims of these areas, structured largely by mobility. It therefore seemed pertinent to ask whether being a teenager in a peri-urban area is harder than being one elsewhere – in other words, when they become independent, acquire the skills that allow them to get around by themselves and explore new places not under parental supervision in the company of their peers.

Thesis title : The place to be? Living and moving in intermediate spaces: Young people and mobility in peri-urban spaces.

Country : France

University : Université Paris Ouest Nanterre (MCSP, Mosaïques, Lavue, ESO)

Year : 2015

Research superviso : Lionel Rougé et Monique Poulot

Teens living in suburban areas on the outskirts of Île-de-France often seem to be victims of these areas, structured largely by mobility. Families choose peri-urban areas in order to satiate their "desire for green spaces 1" and to give their children a healthier environment. Given the ratio of young people to elderly people 2 (three to two), creating "a space for young people" is essential in the context of an aging population. Peri-urban areas have already been studied from the angle of children 3 and students 4. My thesis differs from these works by its focus on a group that is still little investigated 5 — 15-20 year olds — and raises the question of their attachment 6 to a living environment chosen for them by their parents. These teens must find their bearings at, what is for them, a pivotal age.

It therefore seemed pertinent to ask whether being a teenager in a peri-urban area is harder than being one elsewhere – in other words, when they become independent, acquire the skills that allow them to get around by themselves and explore new places not under parental supervision in the company of their peers.

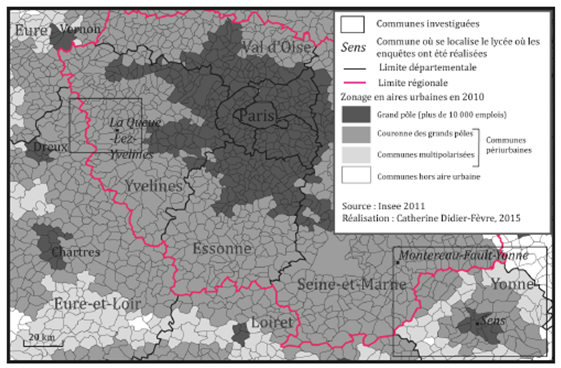

Zoning in urban areas and territories studied

Located a few hundred kilometers west and east of Paris, the areas covered by my thesis more or less correspond to the catchment area for three high schools – Sens (Yonne), Montereau-Faut-Yonne (Seine-et-Marne) and La-Queue-Lez-Yvelines (Yvelines) – all of which are relatively close to the city while enjoying certain rural characteristics, depending on the era of the peri-urbanization movement 7 ; the cantons in the west were concerned earlier by this phenomenon - and in the long term - than those in the east (some of those cantons have only recently become part of this demographic dynamic).

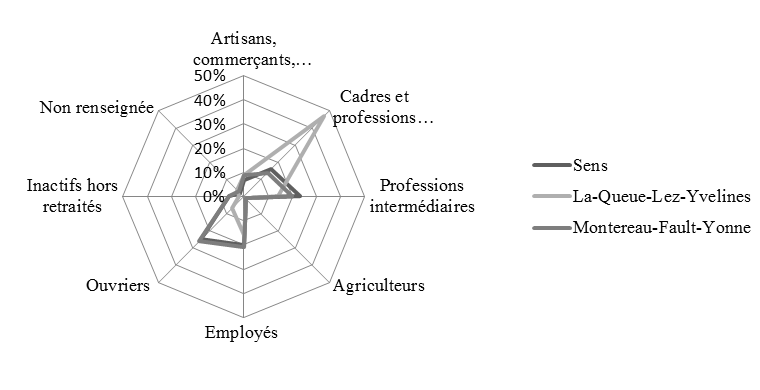

While the sociological profiles of the students’ parents for the three high schools differ between eastern and western 8 Ile-de-France suburbs, surveys have shown a number of convergences when it comes to how young people make use of their living environment and search for attachments.

Sociological profiles of the parents of students for the three high schools

Source: student base at the three high schools

Most young people described their areas of residence as "rural" or "in between" places, but recognized their resources:

"It’s a village. It's not the countryside like in movies. French movies, where there's one road, four houses, fields, old people and no network. Here, there are roads, sidewalks. It’s a village in Seine-et-Marne, not the Creuse, with racist old-timers and an old dog."

To understand this relationship to space, we conducted numerous investigations for the thesis and as part of the broader research program on peri-urban areas of which it was a part

10

These investigations allowed me to consider individual results and avoid sweeping generalizations.

Given the very specific nature of the audience, we used a variety of methods. Approaching young people and getting them to talk is difficult, which is probably why the topic has yet to be explored in greater detail; they are neither highly present nor very visible in the public space 12. Reaching out to them via educational institutions allowed them to talk about what they do "with space". Short online surveys that are easily distributed on social networks is another way to reach young audiences, who are fans of new technology.

Samples surveys of the population, in many cases built via a "snowball effect", do not necessarily lead to generalisations. The use of peri-urban tales helped to "bring life", in narrative form, the various teen figure-types that emerged from the ethnological analisis. Four key figures of the young people living in peri-urban areas emerged from the 85 interviews. The categories, however, were not so black and white, as the last category in particular demonstrates:

• The rooted want to settle in peri-urban areas and, more specifically, the suburban communities they grew up in, where they feel good, have their bearings, friends and families. In the regions east and west of Paris, young people tend to orient themselves towards technological higher studies 13, which they plan to pursue at their current high school (alternating with technical studies, for example), to avoid university cities like Dijon, Orleans and Paris 14. They often evoke financial reasons for not leaving – the weight of the mortgage on the family budget, the lack of scholarship eligibility because of having two working parents, etc. – all of which are characteristic of "modest means 15." Later on, they hope to find work in their suburb and "build" or buy a house 16, counting on family support for the care of their future children.

• Mobile-nomads are very present in the west of Paris but can also be found in the east. They are willing to go abroad for higher education studies or for their future job. However, girls differed from boys in that, while they viewed international mobility as a resource in terms of networks and opportunities, they nonetheless mentioned returning to peri-urban areas to start a family.

• Pragmatics are those young people who "make do" with their peri-urban environments but do not hesitate to leave them – without rejecting them – in order to evolve professionally and/or personally. This category can be subdivided into two sub-groups: 1) young people who arrive in peri-urban areas at adolescence and need a relatively long time to adapt and find their place but who, over time, learn to exploit their resources and 2) young people who could be described as “rooted” but who, being pragmatic, are aware that they will have to leave to secure good futures but plan to come back later. The former, who have developed no particular attachment to their environment, believe that being close to Paris will allow them to commute each day as they continue their studies, which are costly in both in terms of time and fatigue. They plan to work somewhere in the greater metropolitan area and commute, as their parents often do. Their adaptation to their environment is the result of the facilities it provides 17 and the parental mobility model, which plays a key role. The second group shows both attachment to their environment and awareness of its limitations in terms of education and career. Being close to Paris, local ties and resources fuel their desire to live in peri-urban areas in the medium or long term..

• Defectors 18 are those young people who are deeply rooted at the local level and highly involved in associations and community life in general, but who, for reasons of education, leave peri-urban areas. This forced departure from the peri-urban areas that have always been their home reveals untapped resources and opens new horizons. Higher education studies in a university town bring new opportunities and forges new social networks. Others, eager to leave the “shackles” of peri-urban areas as soon as possible, discover an unexpected attachment to them. Because of their layout, their lower population densities, social networks and more relaxed pace (compared to that of metropolises), the return to peri-urban homes allows them to catch their breath between university terms. The home thus appears central in such cases of multi-sited belonging.

Imagining the futures of these territories and the young people who grew up or spent their teenage years in them felt like one of the best ways to bring these narratives and often fragmented comments about the future (with a horizon of 2025) to life. This "Periurban fiction " exercise 19, inspired by literary and prospective works 20, combines both real elements taken from interviews and fictitious ones imagined on the basis of the geographical and social context of peri-urban areas.

This investigation allows us to test the modalities of the unique process of adolescent independence in suburban areas. Far from being captive, young people are highly creative when it comes to mobility and getting to wherever it is they feel like something is happening. They use all the resources these spaces offer and lead lives comparable to those of their urban counterparts by ingeniously combining the opportunities and the means available to them. This includes going out to parties and nightclubs, meeting their friends when they want to and doing sports/cultural activities without having to ask their parents for a ride.

In order to do so they pool the various means at their disposal: parental carpools, rides with friends, walking and hitchhiking, whereas they use of bikes and scooters is limited 21. They often combine modes of transport: walking or hichiking, then taking the train or a car journey. When there are parties, they sleep over so that their parents don’t have to pick them up late. The living space in peri-urban homes tends to be large compared to that of urban ones, allowing young people to have recreation rooms or garages to hang out in with friends, not to mention bedrooms, which are often larger and better equipped (with a private bath or living room) than those of urban apartments. As high school students, peri-urban teens also use their free time to "go into the city" and frequent businesses. Young people quickly understand how to turn a constraint into an asset. For instance, because of the time it takes, a long, tiring tiring commute to school is also a chance to discover the school’s surroundings during free time, unlike some urban students who must return home once class is over 22.

Through their testimonies, a geography of happiness from living in the Parisian countryside - a sense of well-being founded on small daily pleasures and life plans that include peri-urban areas and individual homes - gradually emerges. These young people do not experience being young in peri-urban areas as a punishment, but rather as an opportunity 23 : a chance to live in a healthy environment - undoubtedly less connected but, unlike rural areas, connected all the same – and use the opportunities available to create a livable space and enjoy a rich social life. Ultimately, they are quite happy with their parents’ residential choices because they learn to navigate and appropriate the territory, a skill that strengthens with age.

One of the main lessons from this research is that, even if young people do not initially adhere to their parent’s decision to move to peri-urban areas, they adapt nonetheless and learn take advantage of the situation by appropriating the environments’ emblematic places. The other surprise that came out of this research was concerned with mobility: not only are young people not prisoners of their peri-urban environments, they are in some case even more mobile than their rural and urban counterparts. In this age of exploration and experimentation, they acquire skills relative to mobility, relationships to otherness and the ability to deal with the unexpected, playing on both the local and urban scales. They are more skilled in terms of motility than urban youth and have a more developed sense of space. These skills are assets for their futures.

Because of their malleability and their unfinished/uncertain nature, peri-urban spaces are resources and leave ample room for spatial action, including during adolescence. The public policies implemented for suburban youth by certain innovative local authorities are geared towards making young people actors in their communities. Once active, they choose to stay in these areas rather than go elsewhere, mobilizing the resources they used to make these peri-urban areas places that are good to live in. For example, communities of municipalities can organize initiatives for young people (e.g. youth centers) or support projects run directly by young people (organizing parties and outings) in order to involve them in local life and ultimately strengthen their attachment. But such initiatives are still rare.

These spaces must be the focus of public policies and, more particularly, those targeting young people, a large number of whom live in the suburbs. Taking into account the specific needs of this age group and of peri-urban areas seems essential for strengthening these spaces both now and in the future.

BERGER Martine, 2004.* Les périurbains de Paris. De la ville dense à la métropole éclatée ?* Paris, CNRS Edition, 317 p.

CAILLY L. et DODIER R. (2007), « La diversité des modes d’habiter des espaces périurbains dans les villes intermédiaires : différenciations sociales, démographiques et de genre », Norois, 205.

CAILLY Laurent, 2013. « L’âge du périurbain pluriel », MINNAERT J.-B, Périurbains, Territoires, réseaux et temporalités, Actes du colloque d'Amiens, Lyon, Lieux Dits, pp. 20-28

CARTIER Marie, COUTANT Isabelle, MASCLET Olivier & SIBLOT Yasmine, 2008. La France des « petits moyens ». Enquête sur la banlieue pavillonnaire. Paris, La Découverte, 324 p.

CHOPLIN A., DELAGE M., 2011, Mobilités étudiantes et espaces de vie dans l’Est francilien : les jeux de l’intermédiarité spatiale , CERAMAC, N°29, pp. 49-71.

DANIC Isabelle, DAVID Olivier & DEPEAU Sandrine, 2010. Enfants et jeunes dans les espaces du quotidien . Rennes, PUR, 273 p.

DEVAUX J. (2014), « Les trois âges de la socialisation d’adolescents ruraux : une analyse à partir des mobilités quotidiennes », Agora Débats/Jeunesses. N°68.

DIDIER-FÈVRE Catherine, 2013. « Être jeune et habiter les espaces périurbains : la double peine ? », Géoregards, N°6, Neufchâtel, pp. 35-52.

ESCAFFRE F., GAMBINO M. et ROUGE L. (2007), « Les jeunes dans les espaces de faible densité : d’une expérience de l’autonomie au risque de la « captivité » », Sociétés et jeunesses en difficulté, n° 4 |, http://sejed.revues.org/index1383.html

LOUARGANT Sophie & ROUX Emmanuel, 2010. « Futurs périurbains : de la controverse à la prospective », Prospective périurbaine et autres fabriques de territoires. Territoires 2040. Paris, DATAR, pp. 33-49.

MACHER Guillaume, 2010. L’adolescence, une chance pour la ville . Paris, Carnets de l’info. 264 p.

OPPENCHAIM Nicolas, 2011. Mobilité quotidienne, socialisation et ségrégation : une analyse à partir des manières d’habiter des adolescents de Zones Urbaines Sensibles . Thèse en sociologie soutenue à Université Paris Est. http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/71/59/83/PDF/TH2011PEST1150_complete.pdf

ORANGE Sophie, 2013. L’autre enseignement supérieur. Les BTS et la gestion des aspirations scolaires , Paris, PUF, 228 p.

ORTAR Nathalie, 2005. « Le paradoxe de l’ancrage et de la mobilité en zone rurale et périurbaine », BONNET Lucie & BERTRAND Louis (textes réunis par), Mobilités, habitat et identités, Paris, INED, 92 p.

REMY, Jean, 1996. « Mobilités et ancrages : vers une autre définition de la ville », HIRSCHHORN Monique & BERTHELOT Jean-Michel. (dir). Mobilités et ancrages. Vers un nouveau mode de spatialisation ? Paris, L’harmattan, pp. 135-153.

URBAIN Jean-Didier, 2002. Paradis verts. Désirs de campagne et passions résidentielles . Paris, Payot, 392 p.

1 Urbain, 2002.

2 Sophie Louargant et Emmanuel Roux, 2010.

3 Isabelle Danic, Olivier Davidand Sandrine Depeau, 2010.

4 Armelle Choplin and Matthieu Delage, 2011.

5 With the exception of: Escaffre et al.,2007; Dodier and Cailly, 2007; Devaux, 2013.

6 Jean Rémy, 1996 ; Nathalie Ortar, 2005.

7 Berger, 2004.

8 La-Queue-Lez-Yvelines High School differs from the other institutions in the east of Île-de-France by its socio-demographical composition, with a high proportion of parents with senior executive or intellectual jobs.

9 Didier-Fèvre, 2013.

10 “Les territoires périurbains: de l’hybridation à l’intensité?” PUCA report, 2014. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01145733

11 “Avoir 17 ans dans l’Yonne” (Being 17 in the Yonne) http://www.telerama.fr/monde/avoir-17-ans-dans-l-yonne,119036.php.

12 See the title of the Télérama article.

13 Without this characteristic being exclusive, as general studies students belong to this category.

14 Orange, 2013.

15 Cartier et al, 2008.

16 A way to show one’s social success, in most cases, in the context of a reproduction of family models.

17 Referring to the notion of “plural age of the peri-urban”. Cailly, 2013.

18 The defectors category revealed surprising changes, which were observed thanks to longitudinal follow-up interviews with a dozen young people.

19 In the appendix of the doctoral thesis.

20 2040 territories.

21 Less than 10% of the young people surveyed said they used a bike or scooter to get around in their free time.

22 Macher, 2010; Oppenchaim, 2011.

23 Didier-Fèvre, 2013

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xClassic hitchhiking, an informal mode of transportation, has been supplanted by widespread car ownership and the development of carpooling. “Local” hitchhiking, which has been developing since the mid-2000s, is a safe variation of classic hitchhiking for short daily trips.

En savoir plus xPolicies

Theories

To cite this publication :

Catherine Didier-Fèvre (22 January 2018), « The place to be? Living and moving in intermediate spaces: Young people and mobility in peri-urban spaces », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 10 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/new-voices/12314/place-be-living-and-moving-intermediate-spaces-young-people-and-mobility-peri-urban-spaces