May 2014

The forms in which we collectively imagine social life are often reflected in, and in turn inform graphic material used for propaganda and marketing purposes. A retrospective exhibition of posters on the London Underground offered an opportunity to reflect on the shifting ways in which the changing nature of London and its transport have been conceived of.

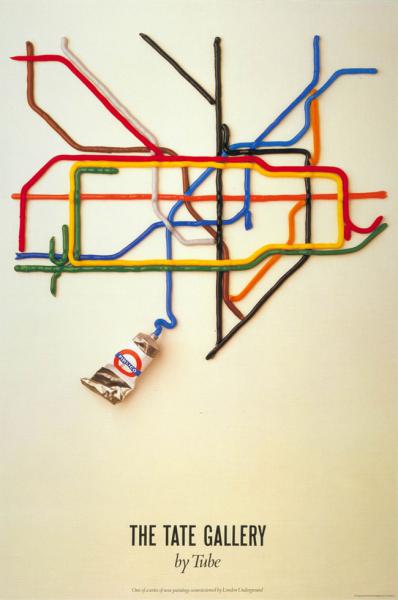

The Tate Gallery by Tube, by David Booth, 1987 (best-selling Underground poster of all time)

Few world cities can claim to have an identity that is so intertwined with its transport system as London can, and still fewer transport systems have inspired the efforts of artists as has the London Underground. It seems fitting then, that the celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Tube included a retrospective exhibition, held in the London Transport Museum, of underground-inspired artwork from over the years.

Like other museums, the London Transport Museum is a place for the creation of memories. The combination of space, objects and narratives, to be enacted as the visitor moves through the museum, helps to shape a sense of a shared past that provides a solid foundation for a shared future (or in this case what London is and where it is going).

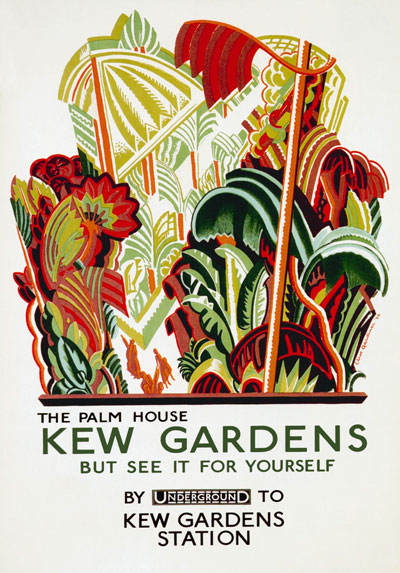

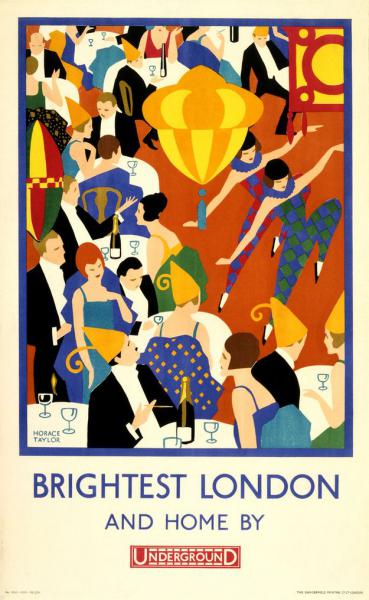

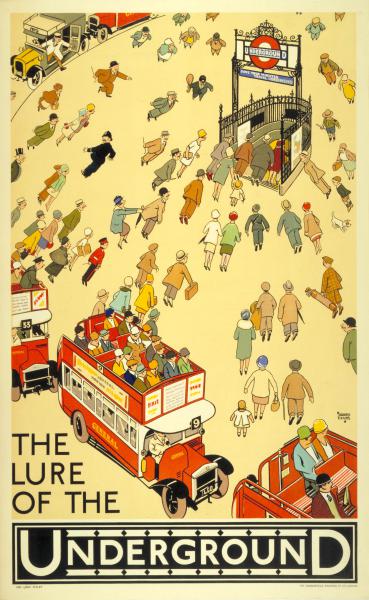

This particular setting, the historical nature of the exhibition, and the very nature of the underground posters whose graphic design always goes beyond the solely instrumental purpose of informing and educating users, to revealing taken for granted understandings of life in the city, were all inductive to reflect on the changing nature of such collective representations that have shaped, and continue to orient everyday life in London.

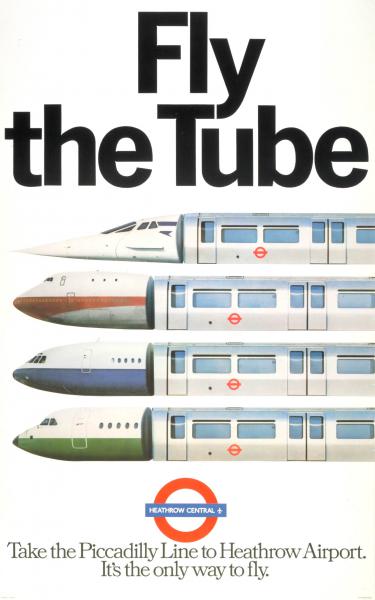

Despite the underground having its genesis in 1863, collectively the posters transpire a sense of modernity and opportunity in a city whose many commercial, cultural and sporting events literally bring the world to its citizen-consumers. Underground passengers move around the city and among strangers with ease and confidence and the very act of using the underground is a civilised and civilising act. This sense of being modern and ‘in’ is conveyed by the latest graphic styles and artistic trends of each respective moment in time. London is always portrayed as a lively city looking optimistically into the future, secure in its identity but never inwards looking, instead increasingly transcending its own geographical confines, such as in the ‘Fly the tube’ poster (below) announcing the line extension to Heathrow airport or a more recent poster showing an imagined map of the underground in 2063 where distant cities such as Dublin, Paris, Berlin, Rome, and New York become stations on newly expanded lines.

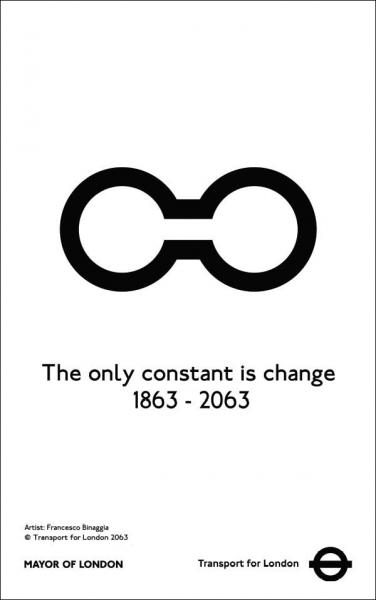

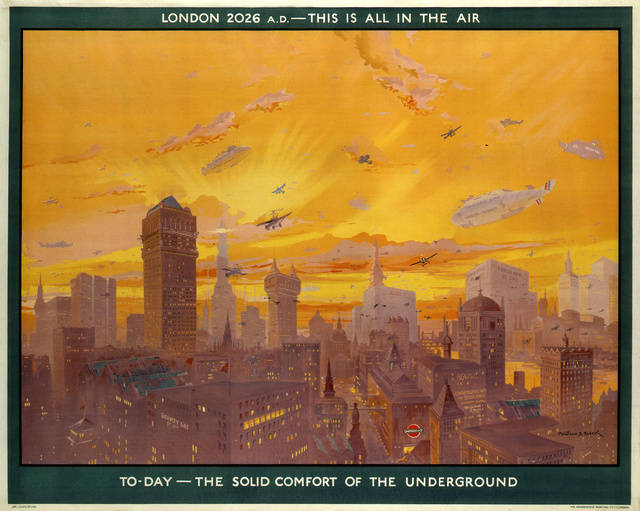

For an event seeking to commemorate a relatively long history, the stress on continuity was not unexpected, and the exhibition succeeded in conveying a sense of permanence in a city characterised by continuous change. Two posters illustrate that this paradoxical sense of permanence and change is nothing new, and yet, always enduring. The first, a modern minimalist design showing the symbol of a transfer station, quotes Heraclitus’ saying ‘The only constant is change’. While very different in design, the second poster, created in 1926, carries a similar message. Its prophetic, futuristic scene of 2026 London, now seems all-too accurate. No, the majority of London’s buildings are not so tall, and small personalised airplanes do not hover above the city. But helicopters and airplanes from the nearby Heathrow airport do cross its skies, and skyscrapers are an emerging feature of its skyline (230 new towers are currently in the planning stages). Yet, in the midst of this urban landscape the discreet red circle of the underground stands as a reassuring beacon of continuity. The heading of the poster informs the viewer that future transport may be airborne, but also that such a future may be exactly that, just hot air. In compared, the solid infrastructure of the underground appears as a reassuring reminder that some things will always be the same. One may wonder whether this ‘solid comfort’ speaks to deeper anxieties of modernity. For sociologist Zygmunt Bauman the greatest challenge for us all is how to learn to live with radical uncertainty. Perhaps the tube removes at least a small part of that uncertainity.

Kew Gardens, by Clive Gardiner, 1926

Brightest London, by Horace Taylor, 1924

The lure of the underground, by Alfred Leete, 1927

Fly the tube, Geoff Senior, 1979

The only constant is change, by Francesco Binaggia, 2013

The solid comfort of the underground, by Montague Black, 1926

Other publications