29 October 2018

In recent years the availability of ICT and the diffusion of fast means of transport have radically changed mobility practices, reducing the impact of spatial distance on mobile people. This research aims to investigate spatial transformations arising from emerging mobility practices, and locates its theoretical background in the field of mobilities studies.

Thesis title : «What Spaces for Highly Mobile People? Analyzing emerging practices of mobility in Italy».

Country : Italy

University : Politecnico di Milano

Year : 2016

Research supervisor : Paola Pucci and Vincent Kaufmann

This research aims to investigate spatial transformations arising from emerging mobility practices, and locates its theoretical background in the field of mobilities studies.

In recent years the availability of ICT and the diffusion of fast means of transport have radically changed mobility practices, reducing the impact of spatial distance on mobile people. This research investigates the following hypotheses.

First of all, building on the definition given by Luca Bertolini and Martin Dijst 1, I suggest that mobility spaces are not only “places where mobility flows interconnect” such as train and bus stations, airports, but all the spaces that support a mobile life. Those spaces are being transformed due to emerging mobility practices, in order to welcome different functions and life domains: the house and the cafeterias can host a small work station for smart workers or the office can be the extension of the house. I then argue that, even traditional mobility spaces, such as train stations or the train carriage, can assume different meanings for mobile people - for example, a central station can be considered a perfect meeting place, likewise the train carriage can be an office on wheels. Finally, I contend that influential movers 2, - people who deeply experience the opportunities afforded by ICT and transport development - appropriate and configure space for their own needs, centring their activities on continuous but distant territories and configuring their own “individual functional space” 3. In so doing they transform urban rhythms and configure new territorial relations, as for example polytopical dwelling and multiterritoriality. Polytopical dwelling suggests a “lifestyle based on a large number of different places, connected by multiple movements and circulations” 4, in this case dwelling is intended as “practicing a space” 5 rather than simply inhabiting a house. Multiterritoriality, instead, occurs when we can simultaneously live in different territories 6. Lastly, Duchêne-Lacroix 7 talks of multi-residentiality and multilocalism and suggests thinking of multi-locality as a rhythm made up of complementary mobility and immobility.

Traditional ‘static data’ analysis, such as supply and demand, or population mobility estimates and projections, based on administrative territorial borders (in the Italian case the city, the province and the region), make it impossible to examine these hypotheses as they fail to highlight the dynamic created by mobility itself. Instead, a methodological approach based on the direct observation of mobile people shows that empirical research methods may help to better understand those processes and to investigate their spatial consequences 8.

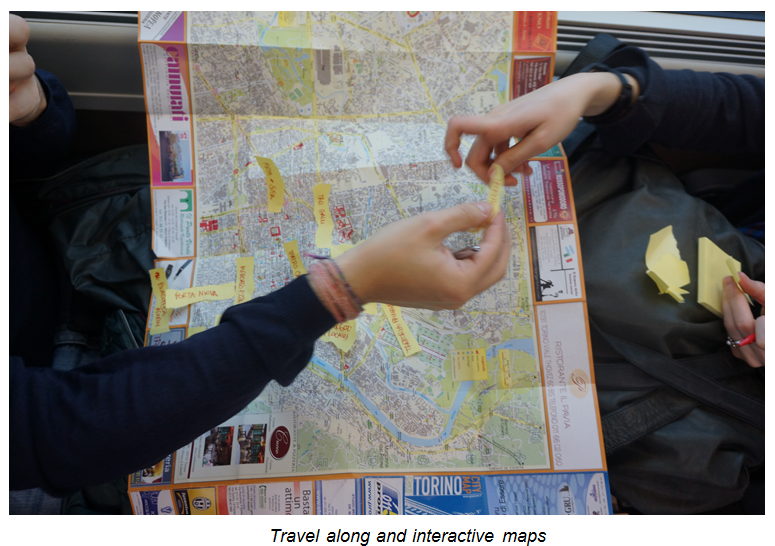

This research is based on the study of 11 people’s everyday mobilities through interviews, ‘travel along’ 9 and interactive maps 10. Interviewees were selected using the snowball technique. They differ in gender, marital status, number of children and mobility patterns (see Table 1). In particular, they are: 11 people aged between 31 and 48 years old, of whom 6 are men and 5 are women. 9 of the 11 are in a relationship, of these 3 are married and 6 are in a common law marriage 11, 4 have children (3 married and one in a common law marriage), while 5 are in couples without children. Four of the interviewees are Long Distance/Long Time commuters (LDC); 6 are ‘double residents’ 12, one of whom regularly spends nights away from home; the last one has moved to a new town and also regularly spends nights away from home and is in a long distance relationship. When travelling by train, they travel by high speed railway. The semi-structured interview was composed of six different sections. The structure of the interview was designed in order to capture the complexity of mobility management, and to investigate the reasons for mobility and the relationships that allow the development of a highly mobile life-style. It has a special focus on the mobility generated by job conditions; nevertheless, it covers different domains of life, with specific attention paid to spatial consequences generated by mobility practices. The data collected contributes to an understanding of everyday mobility stories.

List of interviewees

This research method allows a sensitive and interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of mobility spaces that contributes to describing a territory with “uncertain and evolving limits, independent of administrative boundaries” 13. It also allows all different aspects of life, such as work, familiar relationships, leisure, and relational activities, to be included when analysing mobility. It helps to reconnect the social point of view with the spatial, joining temporal and spatial dimensions and covering different territorial scales; finally, it allows the redefinition of mobility spaces, avoiding an exclusive focus on traditional spaces of mobility and thus confirming the first hypothesis of the research. In the following paragraphs I introduce the mobility stories of two of the cases studied.

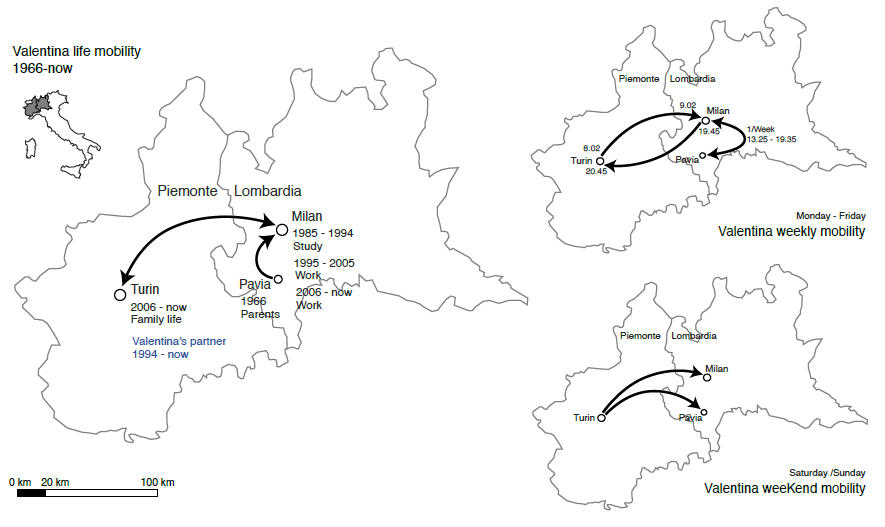

Valentina was born in Pavia, and she is a long distance commuter between Milan and Turin, although Milan is not only her place of work. She lived in Milan for 20 years but decided to move to Turin with her husband when they started a family. This choice was due to many personal and family considerations: economical resources, the real estate market, child care, personal relations and the presence and density of services. Valentina is struggling with her career and professional opportunities on the one hand, and family life on the other.

Valentina’s mobility story

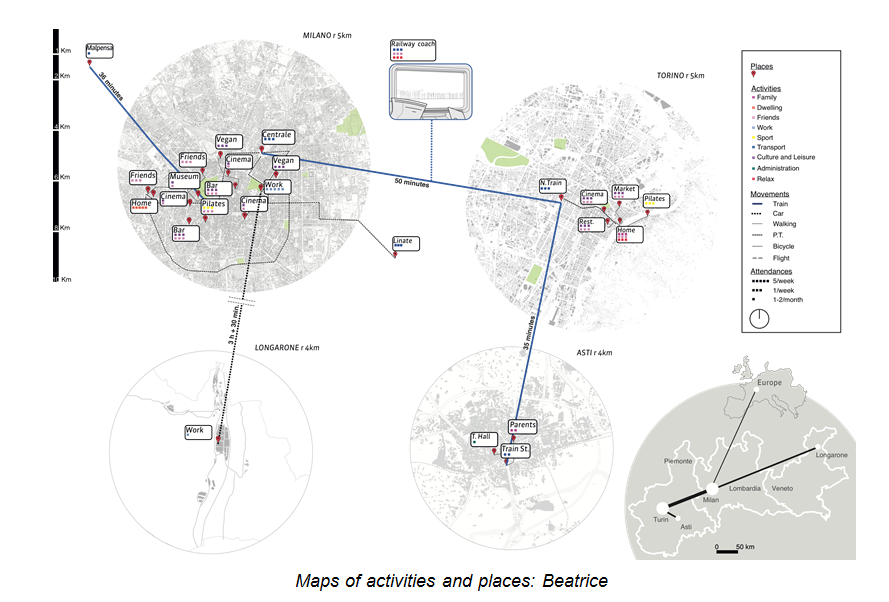

Beatrice used to commute between Turin and Milan everyday, before she decided to rent a small apartment in Milan. Beatrice works in the fashion industry; the company she works for is based in Veneto but she needs to be in Milan. However, her partner lives in Turin. When I asked her where she comes from, Beatrice said: “I could say that my city is Turin, because my beloved one is there. But the rest -cinemas, theatres, exhibitions- is in Milan”. Additionally, her main residence is in Asti, the city where her parents live and where she visits from time to time to see them and for administrative duties.

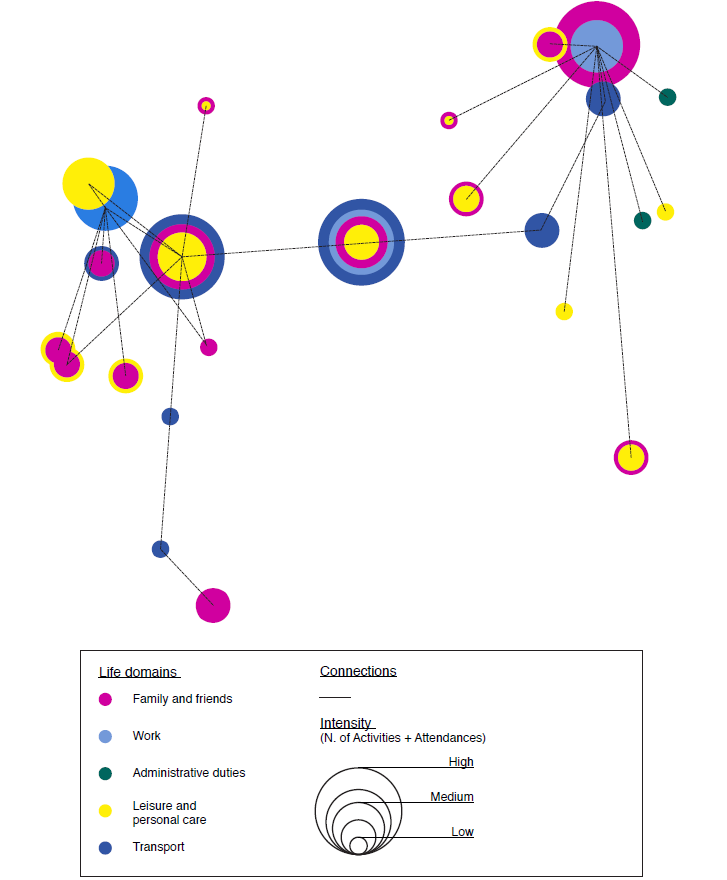

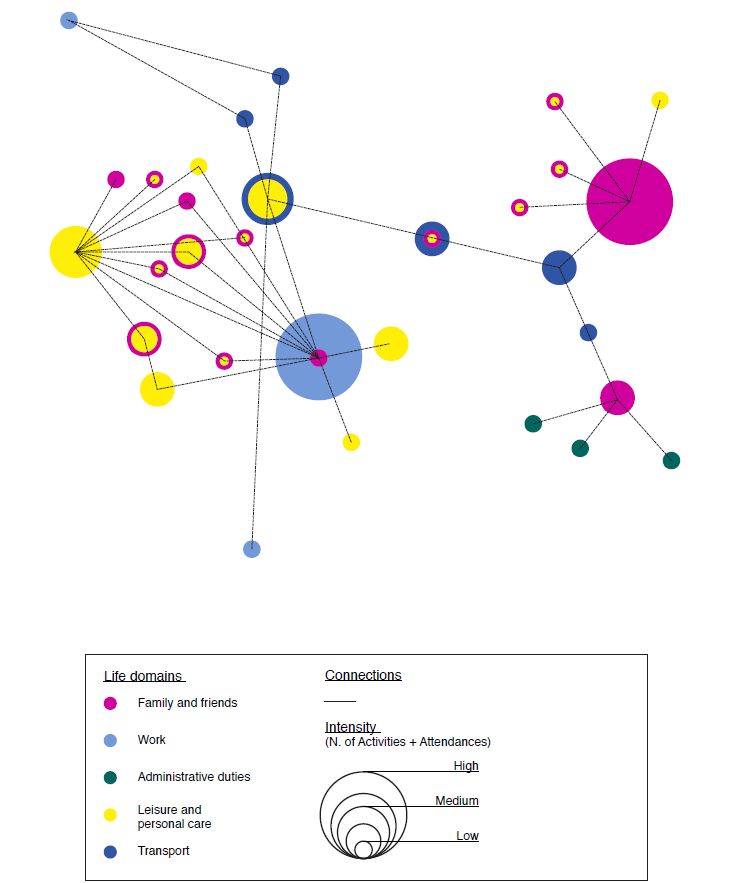

Mobility stories help to highlight how far space and rhythms of highly mobile people have changed thanks to emerging mobility practices. The stories have been turned into maps in order to better describe those changes both in space and time. The maps have been created considering the type and frequency of activities related to a place, while also recording activities undertaken on the move. They are an attempt to represent all those different spaces, geographically distant but in a temporal continuity: “moment places” 14, which are places in space, moments along time and social practices. The dots represent the moment places (spaces, time and practices), while lines are the connections between them (relations). The type of activities is represented in different colours, while the intensity of uses defines the dimension of the dots. The more colourful and bigger the dot the more important the place for the interviewee.

Valentina’s synthetic mobility map

Beatrice’s synthetic mobility map

The maps revealed some important spatial consequences of the diffusion of emerging mobility practices.

First, the growing dimension of the dots shows how long an interviewee spends in a place. Looking at the maps the dimension of the dots clearly reveals the increasing importance of untraditional spaces of mobility, such as the house and the office, for highly mobile people thanks to teleworking, smart working and the use of digital tools.

Second the maps emphasize the coexistence of different territorial scales, and help to visualize the individual “life space” that is “the space inhabited by an individual in everyday life: the house, the working place, the place of leisure” 15. The coexistence of different scales in everyday life highlights the ability to manage space-time relations and engenders “topological relationships” 16 between different places. The research identifies three different innovative ways of engaging with this extended individual territory: profile A defines people who inhabit an extended space, which includes all of the different places encountered in their everyday life; profile B includes people that can clearly separate activities and places, recognizing two main centres of life; profile C groups all the interviewees that experience one of the places as being the most important – the “home sweet home”. And this is independent from the number of other places they inhabit in their everyday mobility.

Innovative territorial relations

Furthermore, the maps show changes in urban rhythms (i.e. the rhythm of everyday routines of a city’s inhabitants) as they highlight the different intensities of those rhythms 17 over the extended individual territory.

Last, and looking at traditional spaces of mobility, the research points out that, in the case of highly mobile people, the regularity of travel transforms routes in routines and makes mobility spaces familiar places in everyday life. Consequently, those spaces assume more complex meanings: "connectivity spaces" 18 and places for "interaction and contact" while on the move. Valentina, for example, says: “I don’t care about the place. I love spending time with my friends. Also the station can be a nice place to meet people”.

Analysing, comprehending and describing the spatial processes linked to the development of innovative mobility practices are particularly relevant for planners and urban designers, though still not completely explored. A large survey conducted in six European countries between 2007 and 2011 19, highlights that “if these new kinds of spatial mobility are still marginal (13% of 25 to 54-year-olds in Switzerland, 18% in Germany and 15% in France), they seem to have increased markedly in recent years” 20. This study also showed that people have become “ready to move or commute over long durations more than ever” 21 due to the need for a job, and that, in some cases, to take “high mobility allowed people to get out of a period of unemployment” 22.

Although available statistics in Italy show that in the last decades certain patterns of mobility have intensified (increase in the number of commuters and length of the commuting journey) 23, an in-depth national study specifically about highly mobile people has not been conducted. However, some important questions arose during my research and suggest future research directions on mobility spaces.

First of all, and consequent to the development of new territorial relations, there is the question of who pays for what when an individual routinely inhabits multiple administrative territories. An interesting approach has been offered by Pier Luigi Crosta 24, proposing a polytopical system of voting based on actual belonging rather than on administrative residence. Nevertheless, it has had no operational follow-up and thus the question remains open.

Another question is related to the management of Privately Owned Public Spaces 25. According to Mitchell what makes a space public is not its “preordained publicness” 26, rather it is the use that some groups make of such spaces. As stated previously, highly mobile people use stations and trains as public spaces, nevertheless, they are privately owned and managed and thus there is a conflict of interest that needs to be solved.

Finally, the house and work spaces are also facing a general reorganization both in their meaning and spatial configuration. On the one hand, it is possible to observe the emergence of more hybrid spatial typology: third places 27. Nadler has referred to those kinds of spaces as “plug & play” 28 meaning a spatial context tailored to respond to mobile people’s needs and that offers all the conditions required for people to be at ease, however temporarily. On the other hand, the overlapping of home and working spaces is making housing and offices more flexible and is bringing about a process of “reorganization or even dismantling of the functional division of urban space into basic functions of housing, work, leisure time, and mobility between them” 29. This process, though fragmented, generates important and diffuse micro-transformations of urban environments and rhythms that still need to be analysed.

1 Bertolini, L., and Dijst, M., 2003. “Mobility Environments and Network Cities” in Journal of Urban Design, 8:1, pp. 27-43; pp. 28.

2 The concept of influential movers is rooted in the work on mobility “pioneers”. Influential movers are mobile people who “create specific arrangements of time and space (…) to realize individual goals” (Kesselring and Vogl, 2004; 5). They exploit the tools offered by ICT and transport developments, blending traditional organizations of space and social time. Due to their lifestyles, however, they inhabit various spaces simultaneously, and build spatial routines and multiple territorial relations.

Source: Kesselring, S., and Vogl, G., 2008. Networks, Scapes and Flows – Mobility Pioneers between First and Second Modernity in Canzler W., Kaufmann V. and Kesselring, S., (eds.) Tracing mobilities. Toward a cosmopolitan perspective, Ashgate, London. pp. 163-179.3 Individual functional space is the territory that results from people’s mobility behaviours. It is “a strategical construction not a model of reality but the result of an action” (Crosta, 2003; 10). It is not a given surface, instead is an animated space and acquires meaning thanks to the practices engaged upon it (Pasqui, 2008; 85).

Sources: Crosta, P.L., 2003. Reti Translocali. Le Pratiche d’Uso del Territorio Come ‘Politiche’ e come ‘Politica’ in Foedus n. 7, 2003, pp.5 -18. Lévy, J., 1994. L’espace Legitime, Presses de la fondation nationale des sciences politiques, Paris; pp. 241. Pasqui, G., 2008. Città, Popolazioni, Politiche, editoriale Jaca book SpA, Milano.4 Stock, M., 2013. “Politopie”, in Levy J. And Lussault M. (eds.) Dictionnaire de la G.ographie et de l’Espace des Soci.t.s,, Belin pp. 794-796

5 Stock, M., 2007. Mobility as ”Arts of Dwelling”: Conceptual Investigations, in The meaning of circulation: moving and Mobilizing Paper given on 22/04/2007 at AAG (American Association Geographers), San Francisco.

6 Haesbaert da Costa, 2005. Haesbaert da Costa, R., (2005) De la Déterritorialisation à la Multiterritorialité in Allemand S., Ascher F. and Lévy J. (eds) Les Sens du Mouvement: Modernit.s et Mobilit.s, Belin, Paris.

7 Duchêne-Lacroix, C., (2013) Caractérisation des Situations d’Immobilité: Réflexions Methodologiques Elements Pour une Typologie des Pratiques Plurirsidentielles et d’un Habiter Multilocal in E-Migrinter – Et l’Immobilit. dans la circulation? Laboratoire MIGRINTER, n. 11/2013 pp. 151 - 167. Available from: http://www.mshs.univ-poitiers.fr/migrinter/ index.php?text=e-migrinter/11sommaire2013&lang=fr.

8 While recognizing the importance of this research approach, there are some limitations. Firstly, the results obtained by a qualitative research method cannot be universally generalized. Qualitative approaches do allow an in-depth analysis of complex issues and, if the sample is large and varied, some generalizations can be drawn but these are limited. Further limits are linked to the involvement of the researcher in the data collection and interpretation that could affect the subjects’ responses, lead to a biased interpretation of the results, or cause important aspects to be neglected. This kind of analysis is also time-consuming and costly both for data collection and interpretation. Furthermore, the need for anonymity and confidentiality of data can necessitate the omission of some results.

9 ‘Travel along’ consists of following people during their regular trips, observing them while practising mobilities, their personal relationships, their use of transport space, the people they travel with or meet during the trip, and finally the devices and, more generally, the objects that ‘travel’ along with them. A similar approach has been applied to driving, see : Laurier, E., 2010. Participant Observation in Clifford, in N., French, S., and Valentine, G., (eds), Key Methods in Geography 2nd edn, Sage Publications, London, pp. 116-130

10 The interactive maps have been designed while travelling along mobile people. I asked the interviewees to fill in the maps of their inhabited cities with pencils and sticky labels, taking notes of the activities they carry out in a normal week and of the places where they hang out.

11 This legal status can be conferred upon cohabiting couples in Italy, however, it is not recognised in all countries.

12 This term is used to describe an individual who lives in one place from Monday to Friday and in another location at the weekend.

13 Viganò, P., 2013. The horizontal Metropolis and Gloeden’s Diagrams Two Parallel Stories, in Oase #89, 2013 OASE Foundation & NAi Publishers, pp. 94-111; pp. 97.

14 Benjamin, Pradel, 2015. «Du long terme de l’ancrage au court terme de la mobilité: système de lieux-moments et échelles temporelles de l’habiter» 4èmes Rencontres Scientifiques Internationales de la Cité des Territoires, Grenoble 25-27 mars 2015; pp. 3.

15 Ascher, F., 2005. “La Métaphore Est un Transport. Des Idées Sur le Mouvement au Mouvement des Idées”, in Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie, 2005/1 Volume 118, PUF, Paris, pp. 37-54.

16 Lyster, C., 2013. Infrastructural Cartography: Drawing the Space of Flows in Sen, A., and Johung J., (eds), Landscapes of Mobility. Culture, Politics, and Placemaking, Ashgate, pp. 239-253; pp. 248.

17 Pasqui, G., 2008. Citta, Popolazioni, Politiche, editoriale Jaca book SpA, Milano; pp. 141.

18 Kesselring, S., 2006. Pioneering Mobilities: New Patterns of Movement and Motility in a Mobile World in Environment and Planning A, Volume 38(2), pp. 269-279.

19 The research Job Mobilities and Family Lives is the first large longitudinal survey studying the interactions between family life, job career, and all forms of work-related intensive spatial mobility in six different European countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, Spain, Switzerland. For more details see: http://www.jobmob-and-famlives.eu. The first wave of the research was carried out in 2007, the second wave was conducted in 2011in Switzerland, France, Spain and Germany.

20 Ravalet, E., 2012. Reversible Mobilities in Forum vies mobiles. Available from: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/reversible-

21 Ravalet, E., Vincent Geslin, S., Dubois, Y., (2014) High Mobility…to have a job? in XIV STRC 2014, Swiss Transport Research Conference, Conference paper. Monte Verità Ascona, May 2014.

22 See note 21.

23 According to ISTAT 2011 general census, in Italy there are 29 000 000 people who commute every day for work or study, the equivalent of 48,6 % of the resident Italian population. Commuters increased by 2.1 million people since the previous census in 2001. Two thirds of these commuters travel for work-related reasons. Workers make longer journeys than students. Mobility time has also increased since 2001, as has the number of people travelling for more than 45 minutes every day. See: ISTAT (2014) Gli spostamenti quotidiani per motivi di studio o lavoro in 15 Censimento Generale della Popolazione e delle Abitazioni.

24 Crosta, P.L., 2003. Reti Translocali. Le Pratiche d’Uso del Territorio Come ‘Politiche’ e come ‘Politica’ in Foedus n. 7, 2003, pp.5 -18.

25 In North American literature on the subject, the term “Privately Owned Public Space” (POPS). was first used in the 1960s in New York City. As a legal oxymoronic invention, it comprises two parts: “Privately Owned” refers to the legal status of the land, while “Public Space” refers to its use (Kayden, 2000)” in W.L. Luk (2009), Privately owned Public Space in Hong Kong and New York: the urban and the spatial influence of the policy, Conference proceedings of the 4th International Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism (IFoU) 2009 Amsterdam/Delft “The New Urban Question – Urbanism beyond Neo-Liberalism”, pp. 697-706.

26 Mitchell, D, 2003. The Right to the City. Social Justice and the Fight for Public Spaces, New York, London, The Guilford Press.; pp. 35.

27 Third places were defined, in 1989, by the US sociologist Ray Oldenburg as referring to places that are neither home nor work. Nowadays many researchers (e.g. Lapintie, 2014; Nadler, 2014) use this word to refer to emerging spaces for working outside the classic office spaces, such as co-working or cafeterias.

Oldenburg, R., 1989. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day. New York: Paragon House.28 Nadler, R., 2014. Plug & Play Places. Lifeworlds of Multilocal Creative Knowledge Workers, De Gruyter Open. Available fr; pp. 382.

29 Di Marino, Mina and Kimmo Lapintie. 2014. “New Spaces For Work In The Public Realm.” Paper presented at Aesop Annual Conference From Control to Coevolution, Utrecht and Delft, Netherlands, July 9-12.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xThe remote performance of a salaried activity outside of the company’s premises, at home or in a third place during normal working hours and requiring access to telecommunication tools.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xReversible mobilities are forms of specific movement made possible by rapid transport network systems. They are made over long distances, with outward and return journeys that are undertaken closely together in time. They are also limited in terms of social mobility and their relationship with otherness.

En savoir plus xLifestyles

Policies

Theories

To cite this publication :

Bruna Vendemmia (29 October 2018), « What Spaces for Highly Mobile People? », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 09 January 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/new-voices/12702/what-spaces-highly-mobile-people