Transport-related greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise in France with no prospect of short-term improvement. In addition, the proposed introduction of a carbon tax was scraped following the Yellow Vests movement. In this context, the Mobile Lives Forum wanted to understand how important travel really is in the daily lives of French people (excluding holidays). This work allows us to imagine effective, fair and practical transition policies to move towards desired and more sustainable lifestyles. This is what we strove to do when we launched the 2020 National Survey on Mobility and Lifestyles.

How much time do the French spend travelling on a daily basis? And how many kilometers do they travel? Are there French people who live entirely locally? Who can do without their car to go to work or to perform their other activities? Who are the main travel-related CO2 emitters? What is the real potential of active modes of transport? What are the urban forms that actually enable a more sustainable mobility?

The survey was conducted among 13,201 people from January 24 to March 5, 2019, including: 1000 people online in each region of metropolitan France (excluding Corsica); and 1,201 people with no more than a middle-school level education (brevet des collèges) interviewed face-to-face from February 19 to May 15, 2019. This prevented the regular under-representation of low-educated people. In order to ensure the sample was representative at the national and regional levels, the data was adjusted within each region according to the following criteria: age, gender, socio-professional category, diploma level and size of urban residential unit. The data was then adjusted at the national level to balance the demographic weight of the regions. Respondents were asked about their travel times. The corresponding distances were assessed by assigning an average speed per type of mode of transport used. For example, bicycles were assigned an average speed of 18 km/h; a half-hour bicycle ride is therefore associated with a distance of 9 kilometers. See the table of average speeds assigned to each mode.

The survey was designed and analyzed by the Mobile Lives Forum. The online questionnaires were administered by Respondi and the face-to-face interviews conducted by Update. The data was processed by Obsoco.

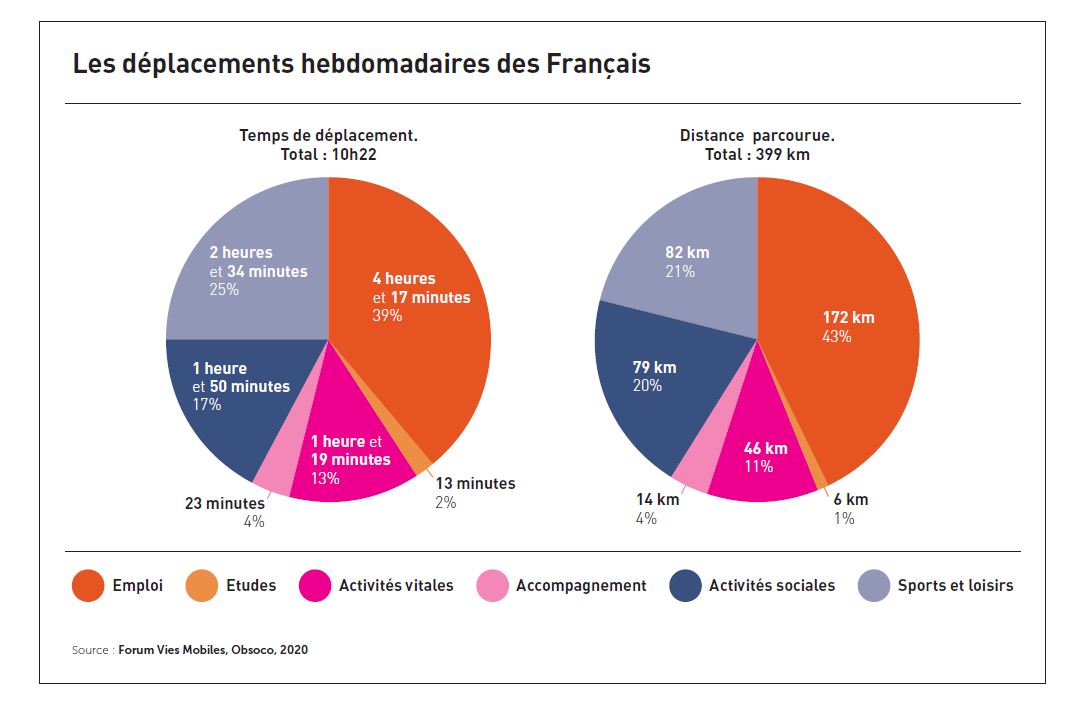

Whether you look at the time spent travelling or the kilometers travelled, the 2020 National Survey on Mobility and Lifestyles shows that usual figures underestimate by almost half the trips made by the French! On average, a French person travels 10 hours a week and covers 400 kilometers, the equivalent of a day and a half of work and a trip from Paris to Nantes each week. With such a large volume of travel, public policies cannot simply rely on changes in individual behavior and the use of active modes to limit CO2 emissions.

This higher reevaluation is partly due to the recent increase in the number of trips we perform, but also to a methodology that highlights trips that were previously not seen. This methodology was designed to better take into account the diversity and variability of travel practices. We find that the 10% of French people who travel the least for all their activities, spend on average just ten minutes a day in transport (about 1 hour per week) compared to almost 5 hours per day (34 hours per week) for the 10% of French people who travel the most - which is over 30 times more! These results show that any transition policy based on averages will be ill-suited to a significant portion of the population.

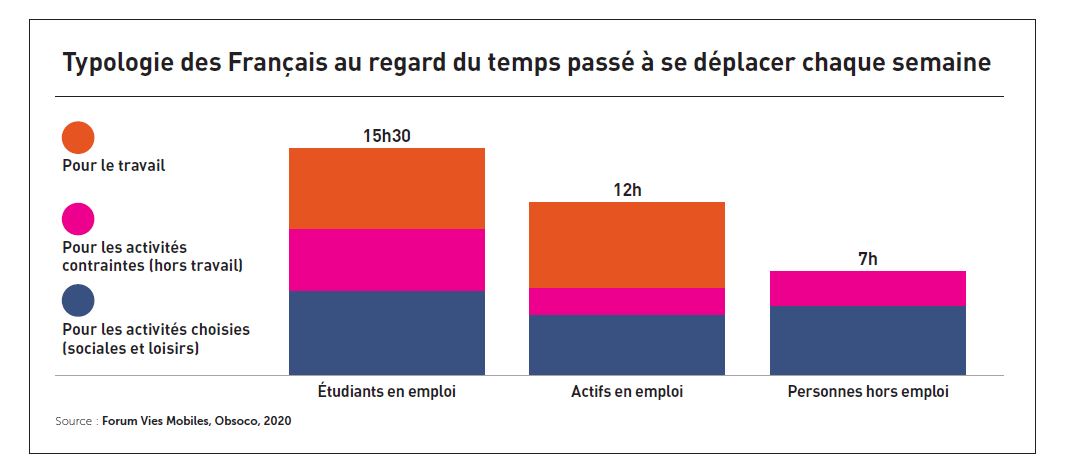

Every week, working people spend nearly 12 hours travelling, covering almost 500 kilometers, while non-working people spend only 7 hours travelling, covering just over 200 kilometers. Work is therefore extremely influential in terms of mobility practices and it isn’t possible to separate employment policy from transport policy.

The diversity and variability of practices has been reinforced by recent changes in our lifestyles: the increasing variability in workplaces and working hours/schedules, the development of digital tools, new school rhythms, varied family cycles within blended families, etc.

It is all the more important to take these developments into account as the survey reveals that the variability of work hours and workplaces greatly increases the time spent travelling: between 1 hour and 5 hours more each week compared to the average.

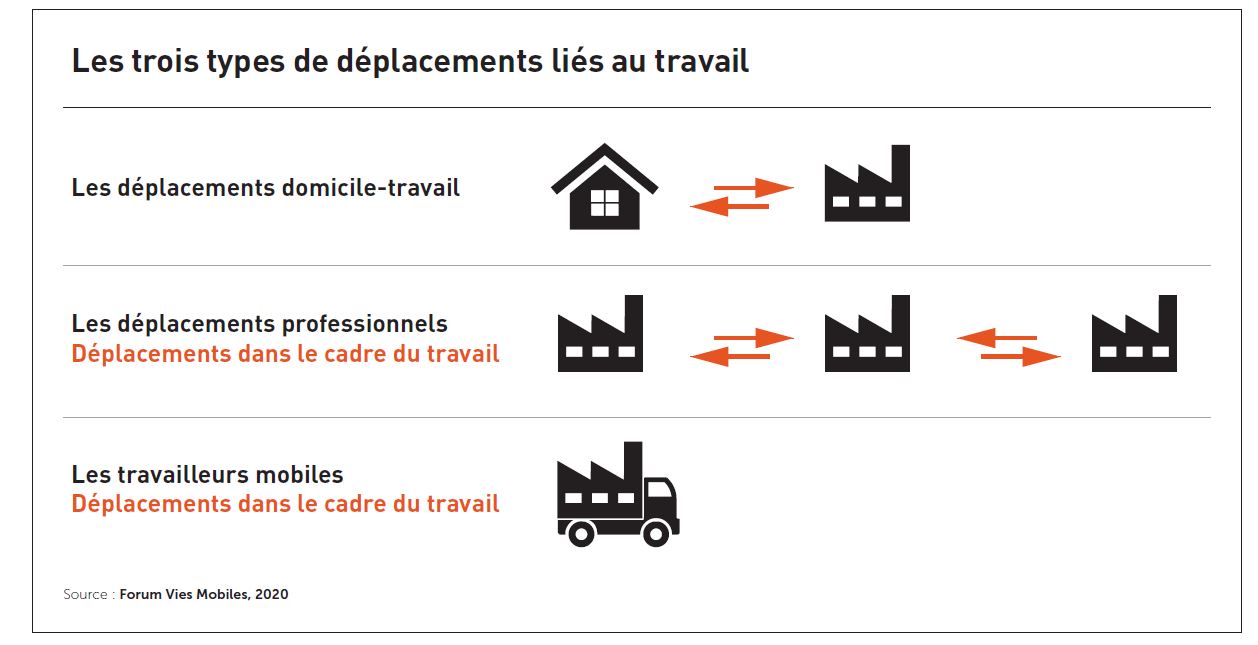

Behind the average figure of five hours of work-related travel, there is actually a wide variety of practices. With more jobs requiring significant travel, particularly in the service sector, transition policies can’t focus solely on commuter trips. This survey reveals for the first time that 40% of French people in employment are mobile for their work, whether they are mobile workers (bus drivers, delivery drivers, etc.) or people who must travel for work on a daily or almost-daily basis (repair and assistance workers, home helpers, sales reps, etc.).

Those French workers are too often forgotten by policies aimed at reducing emissions even though they travel up to 100 kilometers on average each day for their work!

This narrow view of the reality of work-related travel forces us to devise specific policies to enable the transition.

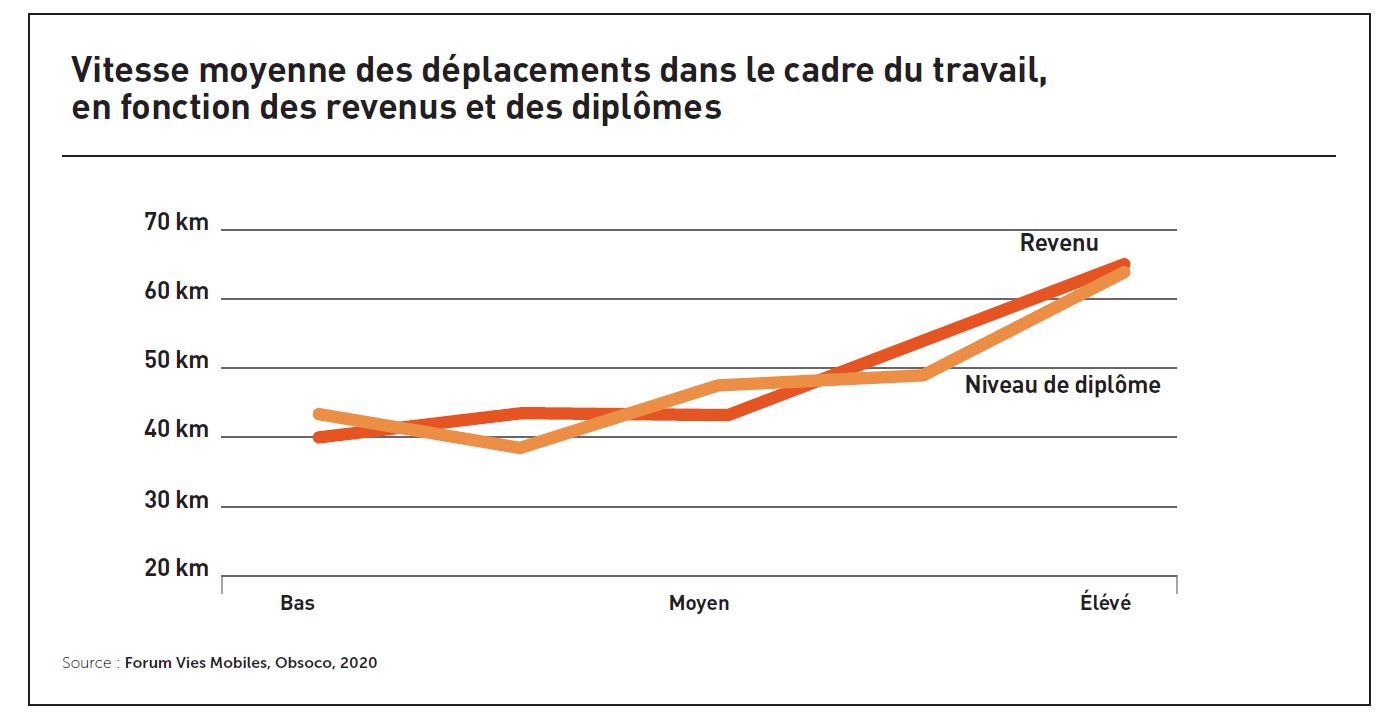

As a general principle, the richest and most educated people travel faster than the others. And while they also spend more time travelling, this is in order to travel significantly greater distances. This relationship is exacerbated when we only look at the trips made by French people who are working: the higher you are socially in terms of diploma and income, the faster you travel: you go from 40km/h to 64km/h! This speed allows the richest to travel more kilometers and the most educated to spend less time in transport.

There is also a difference in the frequency of travel. The kind of work-related mobility that occurs daily and more slowly remains something the working classes mainly deal with. And they also spend more time in transport.

The survey thus proves that there is a strong relationship between socio-economic position and travel practices. Indeed, one is more likely to spend more time travelling and to travel further if one is a man, with a university diploma, with a high-income, living in the Ile-de-France region, without children or with a spouse to care for them. Conversely, one is less mobile if one is a woman, with little education, with modest income, living in an average city and with children.

Contrary to the assumption often made in urban planning - that when you live in a denser city, you travel less - the survey shows that there is no relationship between a territory’s density (number of inhabitants per km2) and how much its inhabitants travel every week.

The amount of travel is mainly explained by the size of the city in which one resides: it is in medium-sized cities, between 10,000 and 50,000 inhabitants, that travel times and distances are the shortest (assuming equal sociodemographic structure). These results call into question the ideal that a metropolitan model, when organized around a dense city, would reduce the movement of its inhabitants.

The practice of telework is also often thought of as a solution to avoid commuting to work and thus, to reduce travel times and distances. However, when telework is performed less than two days a week, it significantly increases travel times and distances, both for work and for other day-to-day activities. And when it is performed more often, at best, it doesn’t change anything. Telework frees up time for other non-work-related travel and makes it acceptable to travel longer distances when going to the workplace as such trips are less frequent.

These results are unexpected and show that teleworking is unlikely to be a lever in the ecological transition without further analysis of how free time is used and what living environments it gives people access to.

With a view to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the results of the 2020 National Survey on Mobility and Lifestyles demonstrate the importance of taking action to reorganize the place of travel in our lives. This requires targeted policies that consider the diversity of French practices.

We propose to focus our efforts on four areas:

1) Local trips: acting immediately

30% of the population performs all of their activities within 9 kilometers of their home (excluding social activities), which equates to 30 minutes of cycling. Yet, some of them use exclusively their cars to do these trips. Here, cycling and walking are major and realistic avenues for a policy aimed at reducing travel emissions. This would allow short car trips to be reserved for people who cannot do without them (because of disability, health, age, transporting goods or accompanying someone, etc.).

2) Rationing travel as a measure of social and environmental justice

The richest and most educated lead lifestyles that require fast and frequent travel. Gradually introducing travel rationing to fight climate change would contribute to greater equality among citizens all the while being effective.

3) Employment, a structuring lever to decarbonize travel

41% of employed workers commute over 9 kilometers, requiring rapid motorized transport. In terms of the transition, these workers who live far from their workplaces represent a real challenge. The survey therefore shows that policies in favour of active modes will be insufficient and that more structuring measures need to be taken at the level of organizations.

Moreover, 40% of French people in employment are mobile in the course of their job. Very few policies are being pursued to decarbonize those trips. While it isn’t possible to change how every job is organized, some practices can still be redesigned to reduce the time and distances of the trips they generate.

4) A policy to reorganize the territory and slow down the pace of life

The survey shows that travel times are the least important in medium-sized cities, between 10,000 and 50,000 people. It also shows the extraordinary nature of the Ile-de-France region, where travel times are particularly long.

These results invite us to reinvent our land planning, to favor medium-sized cities at the expense of large urban areas, and to imagine a policy of social rhythms that gives people the time to travel at slower speeds.

Download the synthesis (in French only)

Download the full report (in French only)

1 People in employment, excluding students

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xThe remote performance of a salaried activity outside of the company’s premises, at home or in a third place during normal working hours and requiring access to telecommunication tools.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xLifestyles

Theories

To cite this publication :

Mobile Lives Forum et L'Obsoco (Research and consulting compagny) (07 January 2019), « National survey on mobility and lifestyles », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 26 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/project/12796/national-survey-mobility-and-lifestyles

Projects by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications