First published in 1990 and republished twice, The Tourist Gaze, by sociologist John Urry, is one of the major works on tourism. In this book, John Urry argues that the centrality of the visual in contemporary culture is mirrored in tourism, and that our desires to visit places and the ways we learn to visually appreciate those places are not merely individual and autonomous but are socially organised. Therefore, changes in tourism are necessarily related to wider transformations in society. Particularly relevant is the changing landscape of class, as not every social group has the same symbolic power to define legitimate forms of doing tourism.

First edition 1990. Second edition 2002. Third edition (with Jonas Larsen) 2012.

A defining aspect of western lifestyles during the post-war period was the growth of tourism. From 1950 to 2000 international tourist arrivals increased from less than 25 million to 697 million. This growth, in both absolute and relative terms, involved large segments of society, especially the more affluent, and holidays came to be seen as necessary for health, education and as a marker of class and status - leisure travel choices now shaped identity. Moreover, to be a tourist was to move with the times; for many it symbolised peace, prosperity and the potential to bring people together.

Although critical voices have long challenged or qualified this positive narrative, it endured most of the century largely unscathed. However, as international tourist arrivals have almost doubled since 2000 (1323 million in 2017 1), dominant forms of doing tourism are being questioned by citizens wondering whether their city, local environment and the planet itself can cope with ever more visitors, holiday miles and greenhouse emissions. As these tensions intensify, social and cultural dimensions of tourism increasingly take centre stage alongside more traditional economic concerns.

For anyone wanting to understand these dynamics, John Urry’s The Tourist Gaze is essential reading. First published in 1990, it was one of the first comprehensive sociological analyses of tourism and, having gone through three editions (the latest in 2011 with Jonas Larsen), it arguably remains the most influential.

The notion of the tourist gaze refers to the pre-eminence of vision in organising the development of Western tourism since the end of the eighteenth century. It emphasizes the social, sensual and discursive character of travel, and concerns both the actual experience of tourists and the production of places for visual consumption.

At the time of publication the originality of the book laid in having brought together seemingly disparate debates about culture, consumption, class, services, architecture, heritage, technology, leisure and the environment around the visual appropriation of places, and discussing them in relation to contemporary examples. In the first edition of the book Urry discussed these issues in seven chapters on theories of tourism, mass tourism and seaside resorts, economies, working under the gaze, cultural changes, history, and theming. The second edition included an additional chapter about ‘globalising the gaze’, examining tourism as a key activity in processes of cultural and economic globalization. The third edition (with Jonas Larsen) included new chapters on photography, performances, and risks and futures. This last chapter emphasises the tourist industry’s dependence on oil and asks whether, in the age of climate breakdown, future generations may look back to the final decades of the twentieth and the first decades of the twenty-first centuries as a heyday of long-distance leisure travel.

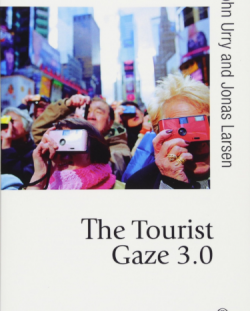

Image 1. Advert from a hotel chain operating in Asia. The discourse of travel as a means for self-development is present in many travel magazines.

Due to limits of space, this review is necessarily selective in the topics discussed and an explicit decision has been made to focus on class considering the current context of growing economic inequalities. Before doing this, in the next section I outline key features of the notion of the tourist gaze.

Tourism is a global reality but one which gains expression in different cultural and political contexts. My own understanding of the concept of the tourist gaze benefitted from field work in Britain and the Spanish and Italian Mediterranean as well as many conversations with John Urry from my arrival in Lancaster in 1998 until his death in 2016. This review considers the tourist gaze mainly in an English context.

Central to notion of the tourist gaze is the idea that our desires to visit places and the way we experience those places are not simply individual and autonomous but are socially organised, and therefore changes in tourism are related to wider transformations in society.

In explaining this idea, Urry’s point of departure is that there is an important visual dimension to our experience of places. This, however, is more than simply travelling to ‘see’ the world. Drawing on the work of cultural historians, Urry argues that there is nothing natural about this notion; it did not exist before the end of the eighteenth century and had to be invented and institutionalised - a whole range of conscious but frequently unconscious work was required before the idea that some places were worth visiting and gazing at came to be legitimised, democratised, and taken for granted 2.

We travel to and appreciate certain natural and built landscapes because we have learnt to look at them in specific ways, in specific social settings and following distinct stylistic conventions 3. Therefore, there are different ‘ways of seeing’ related to distinct styles of travelling 4. These ways of seeing and associated practices are authorised or justified by diverse narratives such as family and group solidarity, nation, education, self-development, pleasure and play, health and heritage. They are more or less attractive and can confer legitimacy and status depending on one’s position in society (class, age, gender, ethnicity and religion) and one’s proficiency in conducting specific activities which are formally or informally regulated (e.g. visiting a theme park, enjoying the beach, walking in the countryside) 5.

It is important to note that Urry does not claim that tourism simply revolves around sightseeing or that other senses are not important. Yet the centrality of vision in tourism mirrors the intensely visual world we inhabit 6. This visual dimension concerns not just the actual experience of places while travelling, but importantly the daydreaming that anticipates the holiday and shapes our expectations.

Image 2. Screenshot of a holiday company advert in the social media platform Pinterest.

Contemporary western culture is predominantly visual and, in the era of mass media, our imagination and desires are shaped by the Internet, television, cinema, and advertising. Appreciation is inevitably mediated by routine engagement with an astonishing number of images that have become ubiquitous in private and public spaces. ‘It is hard to envisage the nature of contemporary tourism’, Urry argues, ‘without seeing how much activities are literally constituted in our imagination through advertising and media 7.’

Image 3. Screens in London’s Saint Pancras station showing a promotional video of a ski resort. The pervasive presence of images shapes our ability to recognise and appreciate places.

Image 4. Screen in an outdoor shop in London showing a video on how to film your holidays.

Image 5. Advertising screens in Piccadilly Circus, London.

For tourism, this means that we learn to appreciate certain places and to ignore or even despise others – the tourist gaze is selective. We find some places more appealing than others and this appeal stems not just from how they compare with other tourist destinations but also from how they compare to places of regular residence and work; there has to be a contrast between ordinary, everyday places and out-of-the-ordinary 8. Yet, just as society and space continue to evolve, so too the boundary between the ordinary and what is worthy of the tourist gaze is not fixed. Mediating this relationship between the ordinary and the extraordinary are many professionals not just in advertising and media but also planners, architects, writers and photographers, to name just some of the most obvious, working to ensure that places become or continue to be worthy of the gaze. In so doing, places are being presented in ways that speak to tourists’ tastes and expectations, and tourists’ tastes and expectations are simultaneously being shaped by these professionals. There is a recursive relationship between the aesthetic appreciation of places and the design and representation of places. Related to this is the argument that not every place and not every form of doing tourism command the same legitimacy, and some social groups / classes have greater influence in defining the legitimate objects of the gaze.

To sum up, gazing in a tourist context involves a learnt disposition that provides ‘some sense of competence, pleasure and structure to tourist experiences 9.’ Different gazes are authorised by different discourses and have consequences for the organisation of places – a whole industry has developed to expand and profit from people’s desires to travel and visually consume places. Professionals working in the design and representation of places strive to make them stand out within a complex system of difference in which what is ordinary and extraordinary is not fixed but changing.

Image 6. Santiago Calatrava’s City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain. Some cities commission celebrity architects to create visually stunning places, raising the level of what is ordinary.

Urry’s account of the rise and fall of the British seaside resort serves to illustrate some of these dynamics and more specifically questions of class, which are addressed in the following sections.

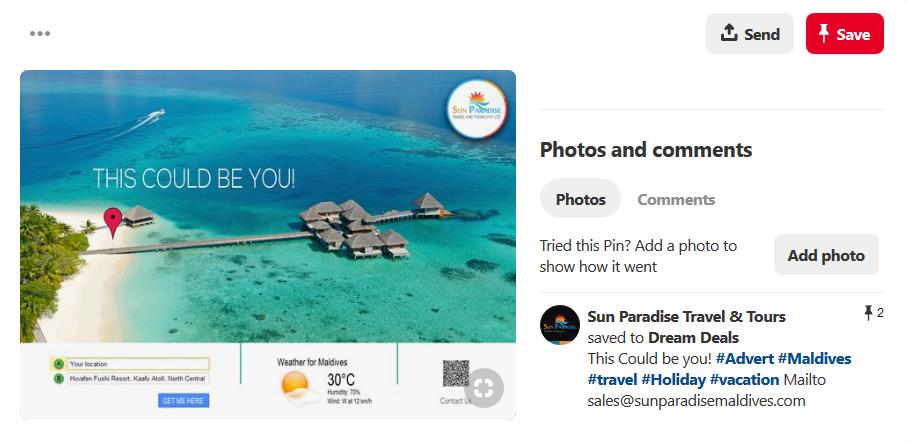

Urry’s observation that ‘The mass tourist gaze was initiated in the backstreets of the industrial towns and cities in the north of England’ reflects his view that a tourist place is ‘constructed in relationship to its opposite, to non-tourist forms of social experience and consciousness 10.’ Therefore, to grasp the appeal of the seaside to the working classes in the nineteenth century, an understanding of urban, industrial life is crucial. Rapid urbanisation, pollution and overcrowding had made life in cities unpleasant and unhealthy. Travel for leisure became a possibility for many as disposable income gradually increased as the century progressed (although extreme poverty still existed), working hours were gradually reduced and routinised for many, voluntary associations helped to promote and grow the holiday movement, and railways enabled easy access to the coast. In addition to these practical changes, there were alterations in social attitudes. Since the seventeenth century, medics had praised the health-giving properties of nature and the sea 11 but in the nineteenth century a growing emphasis was placed on rational recreation to ‘civilise’ the urban working classes, stemming from the romantic belief in the power of nature. In addition, a slow but steady relaxation of morals made the cultivation of some sensual pleasures acceptable.

While this is a simplified account, it shows that the unique system of mass, working-class tourism that emerged in the north of England, in particular in the textile towns of Lancashire in the second half of the nineteenth century, was by no means inevitable. It was the product of seemingly unrelated spatial, demographic, economic, technological, cultural and social processes. Yet these changes created the right conditions for the pioneering of week-long holidays in the north of England, enjoyed en masse by the whole community. For one week, the community lived in a place that was significantly different from their overcrowded, polluted and unhealthy towns. By the sea they found beaches with clean air, promenades and entertainment. This system of mass tourism relied on a novel and distinct spatial and temporal division between the monotony of work and the pleasure of holiday.

Image 7. Blackpool beach, circa 1950s. With easy railway connections to Liverpool and Manchester, Blackpool was the most popular seaside resort in the north west of England during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The presence of others gave the place a sense of liveliness and conviviality.

Image 8. Hand-painted aerial photo of Morecambe in the 1950s showing the pier, beach and promenade, the Lido (open swimming pool) and the art-deco Midlands Hotel. To appreciate the unique character of seaside resorts during the first half of the twentieth century one needs to remember that few people had television at home, most people left their place of residence only during holidays, and leisure facilities like the ones in the photo were to be found only in seaside resorts. For workers in industrial towns and cities these were truly out-of-the-ordinary places both visually and for the number of unique leisure activities they offered.

Seaside resorts developed to appeal to different classes but on the whole they all remained the favourite destination for the vast majority of British holiday-makers and were still the predominant form of holiday on the eve of the Second World War. From the early 1960s, however, many underwent a long decline. As with their growth in the nineteenth century, Urry relates this to wider transformations in British society which now made seaside resorts less distinct and less desirable. The medical profession that had been instrumental in the making of the sea as a place for health now lauded the beneficial effects of sunbathing at the beginning of the twentieth century, shortly thereafter becoming fashionable, first in the Côte d’Azur in the 1920s and soon impacting the holiday season in the northwest Mediterranean. Later, particularly from the 1960s and 1970s, aviation offered holidays in warmer climates to growing numbers of tourists who had previously stayed at the English seaside.

The structuring of identity along class lines had been crucial to the success of mass, working-class seaside resorts. Yet post-war Britain, experiencing further growth in income and consumer choice, no longer wished to be treated as an undifferentiated mass 12. In terms of holidays this meant a shift from old tourism (family, packaged, standardised) to new tourism (segmented, flexible, customised) and seaside resorts struggled to adapt to the changing demands of a new generation of tourists. This struggle was made worse as many towns and cities, and not just tourist places, developed leisure facilities and became ‘beautified’ in a rat race to attract tourists, investment and skilled workers, shifting upwards the level of what is ordinary. Now it was the seaside that had little to distinguish itself from anywhere else. What is more, many of the spectacles that previously had been available only in seaside resorts could now be watched on television and once special events experienced a few times a year became routinely available in one’s home 13.

Image 9. Shopping mall with leisure facilities in Manchester. Such places are designed to be visually attractive.

Another important transformation underpinning the decline of the seaside resort is shifts in class composition. This deserves a more detailed discussion.

The post-war restructuring of the economy produced a shift in the power of different social groups to define legitimate taste and what is worthy of the gaze. Processes of deindustrialisation, gaining momentum in the 1960s, weakened the working classes as a political and cultural force while an expanding service sector underpinned the rise of a ‘service class’ of managers, educators and professionals, including many in media, advertising and design who act as cultural critics and tastemakers.

Unlike the upper classes with relatively large economic assets, the service classes possess more ‘cultural capital’ and their power is symbolic rather than economic or political. Cultural capital refers to the recognition, approbation, sense of confidence, and social advantage derived from participating in ‘legitimate’ cultural activities. Culture is legitimated when practiced and therefore validated by influential individuals and institutions. Some cultural tastes command respect and admiration while others are dismissed. Therefore, our cultural preferences – for music, art, literature, holidays, TV programmes, etc. – are not only a marker of our personal taste, but are also deeply social. Lifestyles allow us to identify ourselves with some while distancing ourselves from others.

For the English seaside resort, in the decades following the war, these changes spelled decline as the growing middle classes began to see this quintessentially working-class destination as coarse and vulgar, lacking in respectability, too close to nature and too far removed from the civilisation of newly-legitimate forms of culture 14.

Image 10. Blackpool beach on a winter day. The pier is one of three in the resort with leisure amenities and dates from the nineteenth century. Still a popular destination, Blackpool is however associated with economic decline and severe deprivation 15.

Image 11. Blackpool tower and leisure amenities in the town centre. The newly regenerated promenade (above) contrasts with the buildings along the seafront and the inner residential areas.

Image 12. Amenities on Blackpool’s seafront. The resort has traditionally focused on a ‘high volume, low income’ travel market and this type of leisure facilities and architecture are often seen as lacking taste by educated middle classes.

Image 13. Guest house on top of a fish and chips shop offering rooms for ten pounds per night.

Image 14. The decline of visitors to Blackpool led to an oversupply of guest houses many of which were turned into ‘Houses of Permanent Occupation’ for incoming workers in temporal low-skilled jobs and relocated homeless people. This resulted in further deterioration of the resort’s ‘social tone’, which continues to be a stumbling block to attract higher-income visitors, in spite of the regeneration efforts.

Image 15. Signs of decline are evident in derelict and abandoned buildings and premises.

Image 16. Heritage plate reminding tourists of the historical link between railways and the development of Morecambe, near Lancaster, as a seaside resort. Along with the regeneration of the promenade, the reopening of the art-deco Midland Hotel in 2008 is part of the strategy to revive the local economy.

Image 17. Abandoned premises metres away from Morecambe’s promenade. The regenerated promenade and hotel contrast sharply with such scenes of decline. The graffiti reads ‘Bring me sunshine’ in reference to a song popularised by British comedians, Morecambe and Wise, the former who hailed from Morecambe.

The service classes did not lack an interest in nature, quite the opposite. But as time went on, and intensifying from the 1970s, theirs became instead an ‘idea of nature’ revolving around the notion of a healthy body, and an understanding of nature as something to be embodied through, for example, organic food, drinking mineral water, yoga and walking in the countryside, camping, mountain holidays. This particular culture of the body became central to the ‘ascetic lifestyle’ pursued by a segment of the service classes working in education, the public sector and welfare professionals 16.

Image 18. Travel magazine for an educated market segment. The discourse of culture, style and cosmopolitanism is a distinctive feature of this type of publication.

Characteristic of the service class is a high degree of conviction in the legitimacy of their cultural activities, a belief in the redemptive qualities of their cultural taste, and a concern with spreading this more widely. From their privileged position in the cultural industries, including traditional and new media, the service classes were able to do so, imposing upon others their own ideas of nature, their own leisure pursuits, and their own understanding of being a proper tourist. Other social groups, especially the upper middle classes, selectively incorporated elements of the ascetic lifestyle not so much substituting other activities but rather adding them to their now more diversified lifestyles.

Amongst this group, high in cultural capital, Urry identifies a preference for what he calls a romantic gaze:

« The romantic gaze involves a solitudinous and lengthy gaze upon aspects of nature such as mountains, lakes, valleys, deserts and sunsets, which are treated as objects of awe and reverence. Other people are viewed as intrusive, as a solitary and contemplative gaze is sought 17. »

The romantic gaze encourages solitude and effort premised on the notion that higher levels of appreciating culture are possible through appropriate aesthetic labour. One should ‘work at’ appreciating places, especially if tourism is seen as a means for self-improvement.

Image 19. Bench with a view in the Lake District. Undisturbed natural beauty is the object of the romantic gaze.

The romantic gaze is in stark contrast with the ‘collective gaze’:

« The collective gaze involves conviviality. Other people also viewing the site are necessary to give liveliness or a sense of carnival or movement. Large numbers of people indicate that this is the place to be. These moving, viewing others are obligatory for the collective consumption of place, as with Barcelona, Ibiza, Las Vegas, the Beijing Olympics, Hong Kong, Dubai and so on 18. »

An atmosphere of conviviality was favoured by the working classes in the seaside resorts. The joy was being part of a group and the absence of other people just like oneself made the site look deserted and lacking appropriate atmosphere (see Image 6 above).

Discussing the class character of the gaze, Urry summarises the service class’ attitude towards the collective gaze: ‘Working-class enjoyment of conviviality, sociability and being part of a crowd is often looked down upon by those concerned to preserve the environment. This is unfortunate as it exalts an activity which is available only to the privileged 19.’

This class character of the gaze is crucial to understanding the dynamics of tourism development. In promoting moral effort and solitude in appreciating undisturbed natural beauty and ‘authentic’ cultures, the service class pioneers travelling to places not yet ‘touched’ by tourism. Yet growing numbers of tourists seeking to gaze in solitude eventually undermine the very conditions of the romantic gaze and ever more new and ‘unspoilt’ areas to be consumed through this gaze have to be found.

Urry’s analysis of the tourist gaze in terms of class formations drew on research conducted in Britain in the late 1980s. At this time, understandings of class focused primarily on the relationship between middle and working classes – this was the social divide that caused most anxiety and concern. Three decades later, as a result of spiralling levels of inequality, the landscape of class is fundamentally being remade. There is now an elite with a vast accumulation of wealth at one extreme of the social ladder, and a growing ‘precariat’ with few resources at the other extreme, while the middle layers look fuzzier and more complex than thirty years ago. Interestingly, this polarization of wealth and privilege is happening at a time when a sense of democratic equality is most pervasive across cultural institutions and both high and low cultures are being celebrated 20. As a result of this, it is now less clear what legitimate culture is and what it is not, and distinctions of taste are being made not so much on the basis of what cultural activities people engage with but by the way they engage and talk about them – the skills showed in exercising judgement in a knowing and sophisticated way 21.

Image 20. Despite much talk about the democratisation of tourism, large segments of the population in western Europe do not go on holidays and flying to exotic places is restricted to a minority.

In this changing context, broad patterns of cultural consumption can be identified 22. On the one hand there are those with fewer resources whose cultural engagement is likely to be more informal and based around the neighbourhood and immediate family (i.e. involving less physical mobility), and less likely to involve activities such as going to museums. On the other hand, the highly educated and better off are more likely to attend more formal activities and can gain a sense of being active and engaged, adding to their cultural confidence and assertiveness 23.

The key questions here are how are these deepening social fractures and new markers of class in the twenty-first century shaping the tourist gaze in Britain? What is the role of the tourist gaze in the transmission of privilege? How is the growing wealth and power of elites shaping built and natural tourist landscapes? Most importantly, in the age of climate breakdown, what is the role of tourism, culture and education in the way elites justify their massive travel-related carbon footprints? Going beyond Britain, how are different class formations in other countries, and especially middle income countries with ‘new middle classes’, shaping different tourist gazes?

Image 21. Advertising poster in the centre of London. In the age of climate breakdown new discourses are emerging to justify tourism and entice people to travel guilt free.

Public authorities, planners, transport providers, and the hospitality industry often think of tourism largely as an economic reality resulting from myriad individual choices that can be influenced by appropriate tools such as changing prices and more information. The concept of the tourist gaze goes beyond such a neat and simplified understanding of tourism and foregrounds its irreducibly cultural, social and technological dimensions. Previous sections have shown how the tourist gaze developed in relation to aesthetic innovations, economic restructuring, new class formations, spatial and temporal reorganisation of life in cities, changing discourses about health, pleasure, nature, identity and education, new transport and visual technologies, shifting moral codes, etc. Changes in tourism are necessarily related to wider transformations in society. Yet, being aware of these does not mean being able to describe and fully understand their dynamics. The concept of the tourist gaze is indeed an invitation to be circumspect about what we can say about tourism, and sceptical about the kind of confident predictions routinely being made about the future of travel. For example, optimistic projections about the growth of international tourist arrivals seldom consider the emerging social, cultural and political tensions regarding growing levels of inequality and concerns about climate change. Surely, the price of flying and the growth of travellers from Asia are important issues when thinking about the projected growth of tourism globally. But an analysis informed by the concept of the tourist gaze would attend to the relationship between a wider set of interrelated issues. First and foremost, it would regard tourism as a phenomenon deeply embedded in mobility and communication systems some of which are going through profound transformations. These systems enable physical travel and the development of aesthetic dispositions to appreciate and compare places (i.e. some of the cultural capital necessary to make appropriate judgements of taste) 24. Related issues would include:

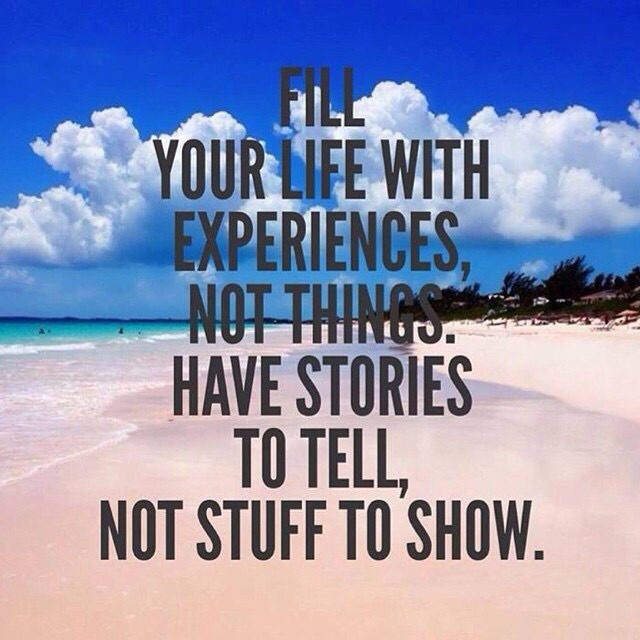

Image 22. Photo of a tropical beach circulated in social media amongst western audiences. Travel experience and the collection of sights rather than material possessions are presented as a sign of distinction. The hidden lie in this image is the idea that long-distance travel leaves no trace on the planet. One way flight London-Sydney generates the equivalent of 120 x 20kg suitcases of carbon per person.

Image 23. Image from a travel blog. The phenomenon of ‘staycation’ – holiday in one's home country rather than abroad, or one spent at home and involving day trips to local attractions – attracted positive media attention during the economic recession and some saw it as heralding a new era of leisure revolving around the enjoyment of simpler pleasures. With the return of economic growth, however, the number of Britons spending their holidays abroad has grown again.

Image 24. A quotidian scene in Spanish seaside resorts. Holidays revolve around a form of collective gaze focusing on the re-encounter of familiar landscapes pregnant with memories and yet experienced as something extraordinary. Tourists often come from nearby areas and holidays in these resorts can be remarkably low-carbon.

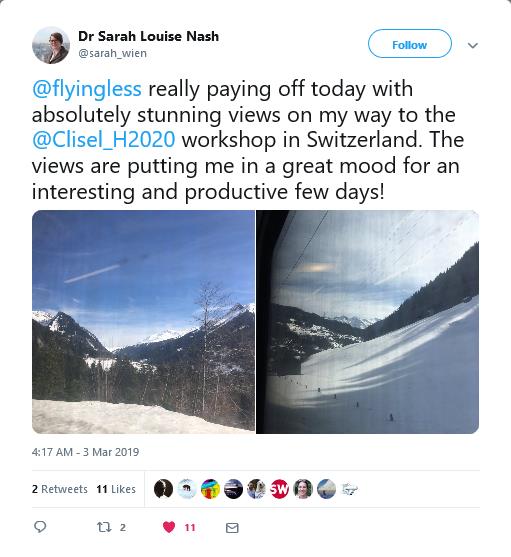

Images 25 and 26. Tweets by researchers travelling by train rather than plane to attend academic events. Supporters of the ‘flying less’ movement often post photos about their train journeys in social media noting the advantages of the train in terms of sociability (quality time with family and friends), comfort, time to rest and work, and the aesthetic pleasures of the passing panorama.

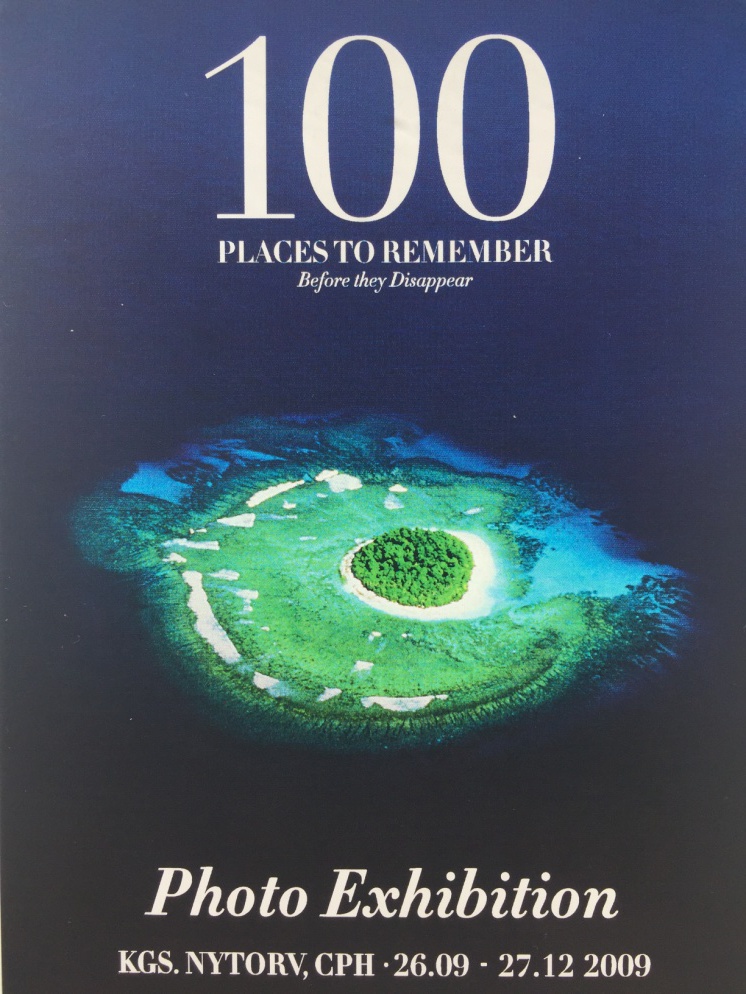

Image 27. Flyer for an open air photo exhibition in Copenhagen during the 2009 United Nations Climate Change conference: ‘100 places to remember before they disappear’. According to the International Panel on Climate Change, "Coral reefs are projected to decline by a further 70–90% at 1.5°C (high confidence) with larger losses (>99%) at 2ºC (very high confidence)." While for some the almost certain disappearance of coral reefs is a reason not to delay a trip to experience them first hand, for others it signals the need to radically reconsider high-carbon holiday habits.

Image 28. The slow travel movement is growing rapidly, especially in Scandinavia where flying less has become part of everyday conversations and is supported by some celebrities. In Sweden the growth of international flying in 2018 has slowed down (from 9% to 4%) and there were fewer domestic and international charter flights than in the previous year. On some train routes bookings have doubled and Interrail tickets sales increased by 50%. In a recent survey in Finland 25% of interviewees said they are flying less in order to prevent climate breakdown, and newspapers in Denmark and Sweden are ‘refocusing their travel sections to cover domestic (and European) destinations easily reachable by public transportation’. Sweden’s third most popular morning newspaper is halving the number of reports about destinations further than a five hour flight, and doubling the number of articles about destinations in the Nordic countries.

Whatever the future of tourism may be, it will be embedded in the profound cultural, social, economic and technological transformations that are being heralded in the first decades of the twenty-first century. The concept of the tourist gaze can help make sense of these transformations, not by allowing us to predict the future but by equipping us with analytical tools to realise what a complex process this may be.

The Tourist Gaze is Urry’s bestselling book and, since its publication in 1990, has been translated into several languages and discussed in academic fields ranging from tourism, sociology and anthropology, to architecture, urban planning, marketing and media. The full range of discussions and controversies generated by this book cannot be fully elaborated on in a short review. In this final section I simply list some of the main criticisms and discuss two of them in more detail. Then I refer to two further issues that I find particularly relevant either because, while being present in the book they seem to have nonetheless been overlooked by researchers, or because they seem largely and surprisingly absent from arguments considering questions of class and global environmental change.

Since its first edition in 1990 The Tourist Gaze has been criticised for neglecting: (i) non-western ways of seeing and forms of leisure travel, (ii) the embodied and multisensual experience of places, (iii) gender, (iv) styles of doing tourism in which sightseeing and the experience of novelty is less prominent (for example, holidays in seaside resorts revolving around the experience of the familiar), (v) individual agency to resist or subvert dominant forms of gazing, (vi) the experiences, aspirations and worldviews of large segments of the population in western countries who seldom travel but experience the world largely through screens 26.

Some of these criticisms were misplaced or based on too superficial or too narrow a reading of the book. Other criticisms constructively pointed at relevant questions for an expanded research agenda. I discuss here only the two first criticisms mentioned above. Regarding the question of non-western ways of seeing, it is important to note that The Tourist Gaze was originally inspired by research on the economic restructuring of northwest England in the 1980s. Readers familiar with this region – its towns, countryside and coastal resorts, its role during the industrial era and its long process of deindustrialisation – will notice its prominence. Although the subtitle of the first edition is ‘leisure and travel in contemporary societies’, during the 1990s Urry became increasingly aware of how much the book reflected an English context. ‘I’m struck’, he noted in an interview, ‘by how incredibly northwest England The Tourist Gaze is 27.’ Had he written it in southern Europe or elsewhere, he observed during a different conversation, the book would certainly have looked different. While the second and third editions reference more cases beyond Britain, it is nonetheless important to remember that Urry’s analysis (and particularly the class dimension of the gaze) is very much rooted in an English context. Having said this, though, it needs to be acknowledged that a reason why this text is regarded as a classic by a large and growing international audience is because the concept of the tourist gaze still speaks in meaningful ways to different cultural, economic and political contexts.

Regarding the question of embodiment, it is necessary to emphasise that this criticism has often been based on a misrepresentation of Urry’s argument. He does not claim that sight is the only sense involved in tourist experiences, that tourism is all about sightseeing, or that tourists simply look at places and do nothing else. Urry’s point is, firstly, that the gaze is socially organised and one needs to attend to various social processes to understand key aspects of tourism; secondly, that the sense of sight organises the other senses; and thirdly, that in a predominantly visual culture we are constantly, if tacitly, making aesthetic judgements about the visual quality of places whether we are actively doing tourism or simply strolling around our places of residence. The second and especially the third edition of The Tourist Gaze respond to this criticism in detail 28.

Finally there are two other issues to mention. These are not criticisms but aspects that are actually present in the book but which have been largely neglected by researchers. The first is the role of places of work and everyday life in shaping ways of seeing and ideas of being a tourist 29. Urry´s insight on the need to understand the connection between tourism and the everyday deserves much more attention even, as he acknowledged, in a context of ever blurred lines between everyday and tourist practices. There are studies about the airport, the car, the beach, the hotel, the heritage site, the hiking trail and the ski resort, to name but a few, but there is a dearth of research on the usually less glamorous everyday places of work and domestic life: the living room, the office, the restaurant kitchen, the hospital ward, the factory, the illegal workshop, and the trading firm. What is the role of these places and their rhythms of life and work in shaping ideas about the role that travel and communication play in our lives?

The second is the role of capital in the planning, design and evolution of tourist places. In the chapter about the fall and rise of the seaside resort, Urry discusses the role of different fractions of capital in influencing patterns of land ownership, types of built landscape and ‘social tone’ that predominated in each resort. Paying attention to elite formations and dynamics of wealth creation and transmission is particularly relevant at a time when real estate is thoroughly implicated in the accumulation of economic capital and the reproduction of privilege.

The intellectual influences in The Tourist Gaze are many and varied, as would be expected from a book that has gone through substantial updates in two new editions over more than two decades. This book and the 1988 paper that preceded it were Urry’s first full foray into cultural studies having previously been largely focused on economic restructuring and in this respect a key influence is Michel Foucault. Other major influences are MacCannell’s book The Tourist, historians of the English seaside resort (particularly Harold Perkin and John Walton), and debates about heritage in England (Lowenthal, Hewison). Debates about globalization and mobilities, embodiment and performance figure prominently in the new chapters in the second and third editions. Towards the late 1990s Urry elaborated more explicitly the relationship between vision and the other senses, drawing on cultural geographers and historians (including Paul Rodaway, Alan Urbain and Lucien Febvre). Finally, an important source of inspiration over the years were his many MA and PhD students at Lancaster University, and especially Jonas Larsen with whom Urry developed a lasting and fruitful working relationship.

A full understanding of Urry’s work on tourism is best achieved by reading not just The Tourist Gaze but also his other books written, co-authored or co-edited on capitalism and globalization (The End of Organised Capitalism, Economies of Signs and Space), leisure, mobilities and place (Consuming Places, Tourism Mobilities, Touring Cultures, Performing Tourist Places), environment (Contested Natures, Bodies in Nature), complexity (Global Complexities), mobilities (Sociology Beyond Society, Mobilities, Mobile Lives), energy and climate (Societies Beyond Oil, Climate Change and Society), and futures (What is the future?). Jonas Larsen’s publications on tourism are highly recommended as well as Rodanthi Tzanelli’s work on tourism and cinema. Tim Edensor’s Tourists at the Taj is a superb analysis of the tourist gaze in a non-western heritage site.

1 51% in Europe, 25% Asia-Pacific region, 16% Americas, 4% MENA, 5% Africa. Source: WTO 2018. Data for domestic tourism is less reliable on a global scale, but in the Mediterranean region it could be four times that of international tourist arrivals. Source: Plan Bleu.

2 Judith Adler elaborates this point in her classic paper on the origins of sightseeing. She argues that ‘the way in which the human body is exercised as an instrument of travel is deeply revealing of the historically shifting manner in which people conceive themselves and the world to which they seek an appropriate relation through travel ritual’ (p. 8). Writing more specifically about the role of vision in tourism she adds: ‘The practices of the contemporary sightseer, so often caricatured with his camera in tow, must ultimately be understood in relation to the (…) problem of attaining, and authoritatively representing, knowledge. They must be seen in relation to forms of subjectivity anchored in wilfully independent vision (…). Above all, they need to be understood in relation to that European cultural transformation which Lucien Febvre first termed ‘the visualisation of perception.’’ (p.8). See: Adler, J. (1989a) The origins of sightseeing. Annals of Tourism Research 16: 7-29.

3 For example, paintings and prints of paintings by Italian landscape artists were highly demanded by the aristocracy and the gentry in eighteenth-century England, and ‘looking over prints’ became a recognised way of getting through the afternoon. Developing a good taste in landscape was a valuable social accomplishment and equipped individuals with the language and the sensibility to appreciate certain places in certain ways during their journeys around the Mediterranean. See: Pemble, J. (1987) The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

4 Adler defines a style of travelling: ‘A body of travel performances may be comparable to a school of painting or to an artistic movement. After the late 18th century, many travellers overtly gave themselves and their journeys such labels as ‘romantic’, ‘picturesque’, ‘philosophical’, ‘curious’, and ‘sentimental’. But in all cases some of the elements constituting a recognisable travel style are reproduced unconsciously, out of common dependence on similar technologies and institutions as well as shared preoccupations rooted in the whole patterns of a group’s life.’ (p. 1372). See: Adler, J. (1989b) Travel as a performed art. American Journal of Sociology 94: 1366-1391.

5 Walking in the English countryside is a legitimate form of ‘quiet leisure’ favoured by authorities, landowners, nature and heritage conservation organisations, and many outdoor leisure associations. There are written regulations as well as unwritten codes of conduct restricting the range of activities which are appropriate. For example, loud music, loud expressions of enthusiasm, walking too fast, or not showing appreciation for the scenery in specific ways and from specific viewpoints are seen as being odd or even out of place. There are also tacit expectations about dress codes and what ages, genders, races and types of bodies one may encounter, and appropriate interactions with fellow walkers. Walking in the countryside is authorised by discourses of health (walking in nature is good for your physical and mental health) and nature (walking is a respectful way of enjoying nature, and contact with nature leads to higher levels of environmental concern). Nature is often conceived of as best experienced in solitude (or at least away from crowds) as landscape, as scenery, and treated as a source of awe and respect. This romantic idea of nature informs a distinct way of seeing (see section below on ‘collective’ and ‘romantic’ gazes). This set of practices, codes of conduct, objects enabling walking, technologies such as cameras and GPS, discourses legitimating forms of being in and enjoying a place, and ideas of what is ‘nature’ and natural, among others, constitute a specific style of performing the countryside.

6 The figures about the scale of change unfolding at this very moment are mind-blowing. Writing in 2015, Nicholas Mirzoeff notes that ‘one hundred hours of YouTube video are uploaded every minute. Six billion hours of video are watched every month on the site, one hour for every person on earth. The 18-34 age group watches more YouTube than cable television. (And remember that YouTube was only created in 2005.) Every two minutes, Americans alone take more photographs than were made in the entire nineteenth century. As early as 1930, an estimated one billion photographs were being taken worldwide. Fifty years later, it was about 25 billion a year, still taken on film. By 2012, we were taking 380 billion photographs a year, nearly all digital. One trillion photographs were taken in 2014. There were some 3.5 trillion photographs in existence in 2011, so the global photography archive increased by some 25 percent or so in 2014. In that same year, 2011, there were one trillion visits to YouTube.’ See: Mirzoeff, N. (2015) How to see the world. London, Penguin.

7 Second edition p. 51.

8 ‘The gaze therefore presupposes a system of social activities and signs which locate the particular tourist practice not in terms of some intrinsic characteristics but through the contrasts implied with non-tourist social practices, particularly those based within the home and paid work.’ (Third edition, p. 3).

9 Second edition, p. 195.

10 Second edition, p. 31.

11 See: Corbin, A. (1994) The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World. Berkeley, University of California Press.

12 Signs of this, even if anecdotal, were already evident in the late 1940s. In 1949 The Times noted: ‘Working class families – having largely driven the middle-class families out of popular large resorts, and having pursued them into smaller more select seaside towns – are beginning to join in the general search for small, quiet ‘unspoiled’ holiday centres, both on the coast and inland.’ See: Walvin, J. (1978) Beside the Seaside. Penguin, London.

13 Discussing these developments Urry argues that ‘people are tourists most of the time whether they are literally mobile or experience only simulated mobility through the incredible fluidity of multiple signs and electronic images’ (Second edition p. 113). The proliferation of images of tourist sites and the de-differentiation of places of residence and holiday led Urry to talk about the ‘end of tourism’, indicating that the boundary between the ordinary and the extraordinary is far more subtle and mobile and, in certain instances, is being eroded.

14 At play here was a ‘moralization of place’ as seaside resorts came to evoke the allegedly vulgar, rough and uncivilised character of the people vacationing there.

15 In Wokingham, Berkshire (SE England), one of the wealthiest communities in Britain, the average person can

expect to live 71 years without disability; in Blackpool, one of the most deprived, the average is 55 years. Blackpool also has some of the highest levels of child poverty in Britain. See: Armstrong, S. (2018) The New Poverty. London, Verso; Hirsch, D. and Valadez, L.J. (2014) Child Poverty Map of the UK 2014. London: End Child Poverty / Child Poverty Action Group.16 See: Savage et al. (1992) Property, Bureaucracy and Culture: Middle-class Formation in Contemporary Britain. London, Routledge.

17 Urry, J. (1999) Tourist Gaze. In Encyclopedia of Tourism, J. Jaffari (ed). London, Elsevier.

18 Third edition, p. 19.

19 Second edition, p. 45.

20 See Lahire, B. (2004) La Culture de l’individu. Dissonances culturelles et distinction de soi. Paris, La Découverte.

21 See: Bennett, T. and Savage, M. (2009) Culture, Class, Distinction. Oxford, Routledge.

22 See: Savage, M. et al. (2013) A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment. Sociology, 47 (2) 217-250.

23 Another important development is the distinction between traditional and emergent cultural capital along generational lines. Traditional cultural activities such as opera, theatre and classical music are favoured by older generations while younger generations show an ethos of eclecticism and are highly engaged in contemporary music, computer games, sport, and so on. This form of cultural capital is characteristic of youth lifestyles with intense use of new media and a strong taste for novelty.

24 This point is extensively developed in Urry’s book Economies of Signs and Space in relation to debates about reflexive modernisation. See Lash, S., Urry, J. (1994) Economies of Signs and Space. London, Sage.

25 For example, in the second half of the nineteenth century, following the rise of railway travel, styles of travel revolving around walking as a better, more ‘authentic’, slow way of experiencing cultures gained popularity. A more recent example is the denigration of the packaged tour bus for keeping tourists in a ‘bubble’, isolated from ‘real’ life. This is opposed to the more multisensual contact with ‘real’ life experienced through walking or using local buses or trains.

26 On average half of the EU´s population does not go on holiday in any given year but this figure varies substantially between countries. According to the statistical office of the European Union, the countries with the highest proportion of the population not participating in tourism in 2016 were Romania (76.0 %), Portugal (74.4 %), Bulgaria (71.2 %), Greece (64.4 %), and Italy (59.1 %). Eurostat’s data on ‘Participation in tourism’ considers ‘tourism trips taken for personal purposes (i.e. excluding trips for professional purposes) of at least one overnight stay’. See: https://bit.ly/2Uieg7O

27 See Franklin, A (2001) The Tourist Gaze and beyond: An interview with John Urry. Tourist Studies 1(2): 115-131.

28 See also chapter 4 on ‘Sensing nature’ in his book Contested Natures (with Phil Macnaghten), and chapter 4 on ‘Senses’ in Sociology Beyond Societies.

29 It is worth repeating here the quotes above: ‘The mass tourist gaze was initiated in the backstreets of the industrial towns and cities in the north of England.’ This reflects Urry’s view that a tourist place is ‘constructed in relationship to its opposite, to non-tourist forms of social experience and consciousness’ (Second edition p. 31).

Movement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xFor the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xLong-distance travel is variously defined, with reference to either distance, travel time, overnighting or being outside of a person’s usual environment. When defined by distance (for example, over 100km), it typically accounts for the top 1-2% of trips.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Javier Caletrío (25 March 2019), « The Tourist Gaze, by John Urry », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 04 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/essential-readings/12906/tourist-gaze-john-urry

Other publications