30 September 2019

In Medellín, the informal neighbourhoods of the north were recognized in the early 1990s and have since been the subject of regeneration campaigns to integrate them into the city. One of the most emblematic projects is the Metrocable, which allows these old enclave neighborhoods to reach the city center. However, when we look more closely, we see that their inhabitants have strong local ties. The right to the city - or at least to access the city center - enabled by the cable car therefore appears to be only one component of a broader integration policy, aimed at developing local life and economy and reducing the need to move so much. So what if, faced with the injunction to mobility, the right to immobility enhanced the quality of life of those living in working-class neighbourhoods?

With a population of 3.3 million people, Medellin is the second most populous city in Colombia. Located in the Aburra Valley in the heart of the Central Andes, the city expanded from the 19th century on a north-south axis along the Medellin River. The particular topography of the location, with steep mountain slopes, influenced the city’s urbanization process, which intensified during the 20th century in the center and south of the valley, until the population explosion in the 1980s that caused an unprecedented phenomenon of urban informalization and led to the occupation of the northern slopes. The resulting urban expansion has since extended beyond the official boundaries of the city, characterized by self-construction and a lack of infrastructure and public services.

While public policies initially oscillated between interventions to eradicate these informal constructions and compensatory rehabilitation plans, the municipality finally officially declared a desire to integrate informal settlements into the economic, spatial and social dynamics of the city. The state then started regularizing and legalizing land ownership and informal settlements, supported by occasional actions by the municipality. In 1991, Colombia's new constitution was accompanied by the launch of the first Integrated Program for Improvement of Informal Neighbourhoods (PRIMED). The government's goal was to recapture these territories that were plagued by urban violence, by improving the living conditions of their inhabitants. The adopted strategy aimed to reclaim the “centers of citizen life 1” by setting up urban infrastructures and making public services available to citizens.

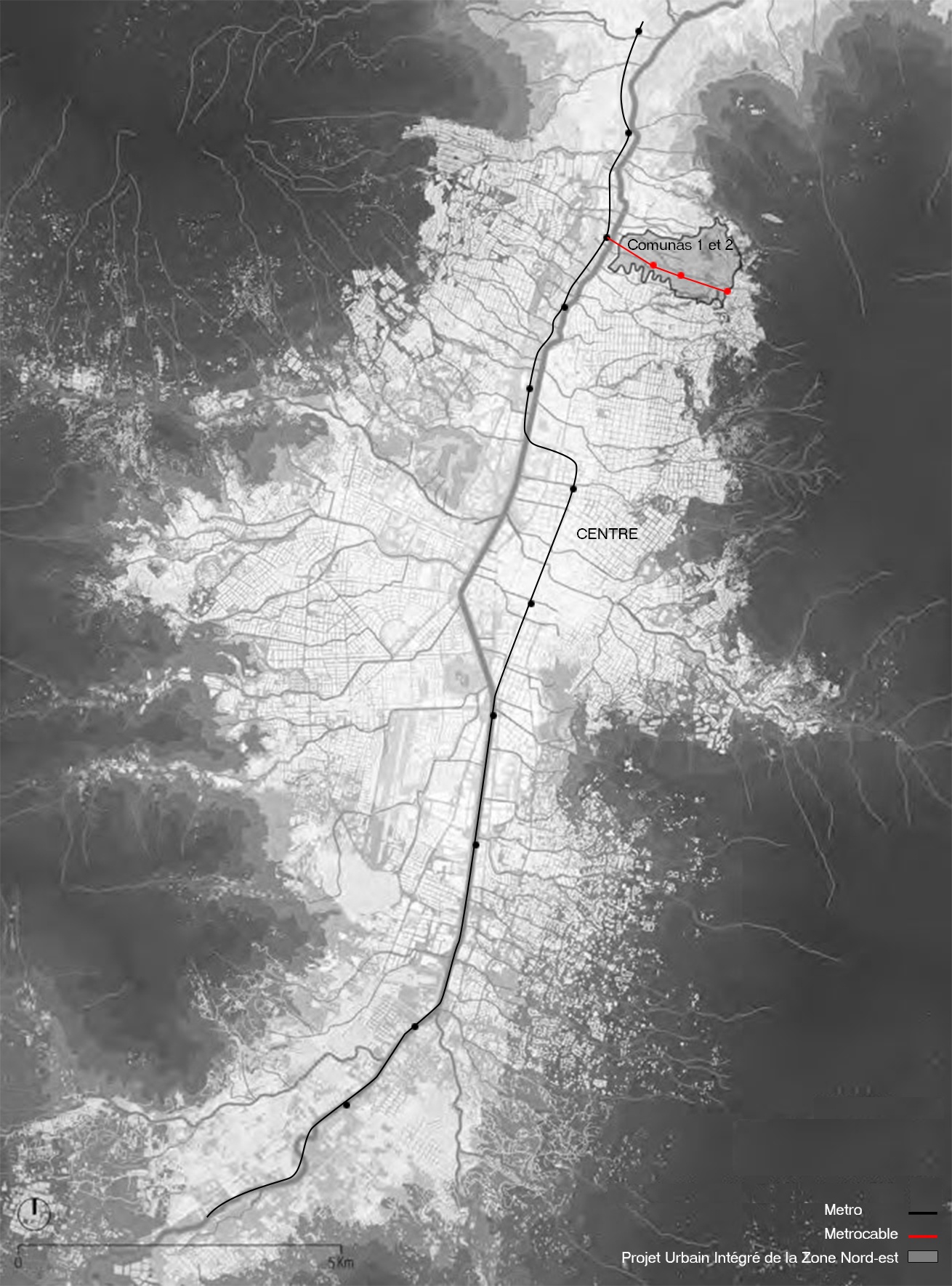

However, despite this urban policy, the city of Medellin continued to suffer from a socio-spatial segregation with a strong north-south polarization. The south and center of the valley, where most of the city’s jobs are concentrated, are where the upper classes prefer to live, while the northern districts, where the lower working classes live, are mainly territories far removed from the economic and social dynamics of the city. The significant daily commutes generated by this urban situation caused the city’s public transport systems and road network to be saturated. Urban planning strategies in the 2000s initiated an urban re-qualification process, including the implementation and development of new mobility services. Among the proposed projects were the city's first cable car, dubbed the Metrocable (2004), and the first Urban Integration Project (PUI) that aimed to implement a series of urban interventions in comunas 1 and 2 of the Northeast Zone 2 - which is where our investigation took place.

It appears in these projects that public policies recognize a relationship of interdependence between one’s mobility and right to the city, defining transport as a necessary condition for access to the opportunities offered by the city (in terms of education, health, culture and leisure). However, by installing a cable car, the authorities also forced residents to spend more and more hours in transport to get to their workplace and/or their home. Was it not therefore possible to claim that the government's actions in this sense contributed to some form of injunction to mobility? What if working and living in the same neighborhood was to be considered as a factor contributing to people’s quality of life? To answer these questions, the first part of the article will highlight the success and limitations attributed to Metrocable in improving the inhabitant’s living conditions; the second part will then analyze the effects of the Urban Integration Project on the revitalization of local urban centralities, as well as on the city’s overall economy; and finally, the third part will develop a reflection on the “right to immobility,” made possible by the economic independence of comunas 1 and 2.

Comunas 1 and 2 in the Northeast zone of Medellin, which were largely urbanized informally, benefited in the 1970s from the implementation of an orthogonal road network and formal subdivisions that are now the main feature of the lower part of comuna 2 (Andalucia, La Francia, Villa del Socorro and Villa Niza). These neighborhoods were consolidated and their density increased by the rapid demographic and urban growth experienced by the city in the second half of the 20th century, shaping them as they are today. These steep areas are therefore characterized by self-built housing and winding streets, alleys and pedestrian paths that make up their circulation network. Prior to the government's urban interventions in the 2000s, residents suffered from precarious living conditions due to the lack of urban infrastructure (water, electricity, gas, telecommunications, sewers) and public services (health, education, culture, recreation), the poor quality of their homes (materials, foundations, unstable terrain, etc.), as well as the lack of accessibility caused by the steep terrain.

To the public authorities, the Metrocable therefore appeared as an effective solution to make this territory accessible, because of its ability to cover large distances without occupying much ground space. Travelling 2,072 metres in about 15 minutes, the K line consists of three stations serving the Andalucia, Popular and Santo Domingo neighbourhoods, and an intermodal station called Acevedo. The Metrocable stations were initially intended to serve the areas of comunas 1 and 2 with the largest flow of people, in order to ensure a satisfactory attendance rate. As a result, they “strengthened the existing urban centralities 3” which were already characterized by their commercial attractiveness prior to this infrastructure.

The connection to the Acevedo station with the city's only metro line (which runs along the Medellin River on a north-south axis) has improved the accessibility of these northern districts to the center and south of the city, where the majority of opportunities in terms of employment, education, culture and leisure are concentrated. The government thus came to consider and define the cable car as an “engine of social inclusion” – as demonstrated by the twelve million passengers who ride the Metrocable every year.

Figure 1: Medellin's Metrocable, comunas 1 and 2.

Source: Corporación Comuna 2, 2017.The impact of the cable car on people's lifestyles was revealed in a series of interviews with residents in September 2017. It shows that the infrastructure has improved the inhabitant’s mobility conditions by offering more comfort (quality of equipment, seating) but also by simplifying some trips that were previously made on foot or in crowded buses: "Before, I had to walk, because I couldn't afford the bus"; "It's more comfortable, because the spaces are bigger than on the bus. It's safer too, because the buses were under attack.” People also made some welcomed savings with the introduction of the Civica pass in 2012, that allowed users to ride both the metro and cable car for the price of a single ticket. The inhabitants of comunas 1 and 2, who used to need two buses to get to the “official” city, went from buying two tickets worth 3,200 pesos, to buying one ticket worth 2,150 pesos, saving a third of the price of each trip.

And if most respondents say they are satisfied with this new equipment, it is primarily because of its speed. Because using it has halved the amount of time spent in transport. Residents testify: “Before, we used to take the bus and we had to walk. It changed our walking habits. On average, we’ve gone from 1h-1h30 to 40 minutes [total trip time]"; "It is faster than the bus which took 1h30 because of congestion, compared to 30 minutes with the Metrocable"; "People love the Metrocable because it's fast." With all this freed-up time, people can now spend it with family, or dedicate it to leisure, or associative, academic, religious or other kinds of activities. 4 It has also opened up opportunities for work and study, in that it allowed people to perform several activities within the same day, like this resident of comuna 1, who works every morning from 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. in the neighborhood Colors (southern part of the city), then develops community activities in Santo Domingo in the afternoon (northern part of the city), before going to Robledo University in the evening, from 5pm to 10pm (southern part of the city).

Finally, part of Metrocable's success rests in its successful integration into the city's transit system. The quality of its infrastructure, the use of a common signage with the metro, the ease of access from the Acevedo station, and the advantageous fares it offers are all factors that have spared it from being seen as a “transport system for the poor.”

However, while the Metrocable has helped open up comunas 1 and 2 by promoting access to the main employment pools and all public services located in the center and south of the city, the saturation it suffers from today and the phenomenon of comunas 1 and 2 becoming largely residential areas seem to demonstrate the limits of the operation.

Between 2001 and 2004 (a few years after the introduction of Metrocable) there was a phenomenon of comunas 1 and 2 becoming places of residence alone, revealed by a decrease in real estate transactions related to businesses and services (estimated at minus three points by Julio Davila's study and data from the Medellin Real Estate Market Observatory 5), which leads to a decrease in the attractiveness of local centralities and thus in the neighbourhood’s life. The saturation of the Metrocable from 2012, forcing users to wait more than two hours to be able to board the cabins during peak hours (from 4:30 a.m. to 6:30 a.m., then from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. in the evening), is another remarkable fact. It’s a phenomenon that affects the entire city’s transport system, as noted here by the inhabitants: "In the end, it didn't change much, because the cable car is very slow. The line suffers from congestion and stops when it rains"; "At rush hour, the buses, the metro and the Metrocable are all full."

This leads us to believe that the implementation of this transport infrastructure, encouraging residents to move outside their neighbourhoods to perform their daily activities, has in the end contributed to condemning these newly connected neighborhoods to a solely residential function, all the while increasing people’s need for mobility. These observations allow us to question the ability of public policies to solve problems of socio-spatial integration, when they are only focused on transport-oriented measures.

Figure 2 : Saturation of the Metrocable during rush hour.

Source: Camille Reiss, 2017.Aware of the “perverse” effects caused by urban interventions that focus only on transport measures, the municipality launched in 2004 the city’s first Urban Integration Project (PUI), as part of the city's urban development plan named “Medellin: Commitment of all Citizens.” The goal was is to “promote local development, reducing the need to move to other parts of the city, in order to counter the pressure towards the center and strengthen the development of more autonomous centers.” 6 While the Metrocable project was aimed at improving access to the main employment-generating areas (the center and south of the city), this time the government aimed to improve the living conditions of the population and help to energize neighbourhood life.

The government therefore set up an urban project defending the values of “social urbanism,” based on a transparent, participatory and communicative planning policy, which promoted education, inclusion, culture, conviviality and entrepreneurship. It defined civil society participation as a key tool for monitoring the development plans at all levels and was, according to the government, an opportunity to rebuild and redefine the concept of the “collective.” Its establishment in the Northeast Zone was decided and influenced by the presence of the Metrocable, considered by the municipality as a “potential engine of intervention.” 7

Map 1: Tracking the Metrocable K line and the Urban Integration Project of Medellin’s Northeast Zone.

Source: REISS Camille, 2019 ; URBAM EAFIT, 2013, p. 26.This method of urban intervention was innovative in its political and management aspects, such as:

Together with the Community Action Councils (which existed before the urban renewal projects), local communities were invited to participate in all phases of development, from diagnosis to construction.

Prior to the government intervention, the sectors of Andalucia, Popular and Santo Domingo were characterized by a lack of infrastructure and public services, the virtual absence of public spaces and sidewalks (making it hard for pedestrians to get about) and the lack of connections to surrounding neighbourhoods due to the river basins seperating them. The Metrocable stations that serve them were therefore defined in the PUI as “points of reference and conviviality” 8 that must contribute to the development of neighbourhood life. Particular attention was given to the urban organization of the nearby spaces, in order to strengthen their relationship with the surrounding urban fabric, in particular with the main roads surrounding them.

The rehabilitation of Street 107 in the Andalucia sector was one of the PUI’s most important projects. It consisted of rehabilitating existing public areas, reducing the space dedicated to cars and increasing the width of sidewalks, but also creating footbridges allowing connections with the adjascent neighbourhoods, including the Andalucia - La Francia bridge at the Herrera and Juan Bobo river basins. These interventions were also accompanied by the construction of public parks, in places previously identified by the community as opportunities to create new public spaces. Then, a relocation project was built in the Juan Bobo river basin, dedicated to families whose homes built on unstable soil were considered precarious.

Finally, at the Popular and Santo Domingo cable car stations, new stairs and walkways helped promote inter-neighbourhood links, access to the España library park and the revitalization of existing shopping streets. A series of programs was also implemented, including a health center, a sports field, a courthouse, as well as a set of public spaces and gardens. The urban and architectural quality of public infrastructure, buildings, spaces and gardens built under the PUI was justified by the government's “historical debt” towards underprivileged neighbourhoods. The slogans carried by the mayors who initiated the Metrocable and PUI projects thus claimed their desire to offer “the most beautiful to the most humble” in order to “activate the power of aesthetics as an engine of social change.” 9

Figure 3: A public garden built as part of the Northeast Zone’s PUI in Medellin.

Source: Corporación Comuna 2, 2017.All these measures demonstrate how government-initiated urban interventions have benefited the population. The centralities of comunas 1 and 2 (Andalucia, Popular and Santo Domingo) have been boosted by the implementation of a series of facilities related to culture, education, health and leisure. The stations and library have been identified as urban markers, due to their spatial and architectural quality, even though they were located in one of the most disadvantaged areas of the city. Inter-neighbourhood accessibility has been developed with new stairs, walkways and pedestrian pathways, and the quality of life has been improved with the creation of public spaces and gardens, as well as a significant decrease in violence. This success was also attributed to the state’s financial support of the project, investing the equivalent of seven times the price of transport infrastructure over the four years following the Metrocable’s inauguration.

One of the key points of the Northeast Zone PUI is the strengthening of local economic activity in Comunas 1 and 2, with the aim of boosting the “global economy of the city, that only had low growth at the time,” 10 and thus combatting social inequality. This led the state to provide financial aid to local micro-companies. A set of institutional tools was offered to inhabitants, pursuant to a political will to democratize and decentralize the economic management bodies of the city. The “Culture E” programme, dedicated to entrepreneurial culture, was thus intended to encourage “the creation and development of new enterprises that meet the needs of the market and the dynamics of regional productive chains” 11 in order to increase their economic potential by building on entrepreneurs' capacity for innovation.

An entrepreneurial development center called Cedezo was later set up in Santo Domingo (comuna 1), to facilitate access to the various services offered in terms of training, access to credit, specialized consultations, etc. The “opportunity bank,” 12 promoted by Mayor Luis Pérez (2000-2003), allowed the population to access small loans repayable over a flexible period, offering microloans of up to US$2,500, with monthly interest rates of 0.91%. This support ensured the long-term survival of small street businesses. In fact, between 2004 and 2009 there was an increase in the number of small businesses (estimated at 113% in comuna 1 and 164% in comuna 2), as well as an increase in wages linked to the formal and informal local economy (exceeding the legal minimum from 2009). 13

In 2009, there were 4,521 companies in Medellin's comunas 1 and 2. 14 Most of them were located in the most attractive areas of the community, which were consolidated with the arrival of the Metrocable. Organized in an associative way, they benefit from the effects of “agglomeration economy,” which combines spatial proximity with economic benefits derived from the density and diversity of economic agents at the local level. They benefit from an effective local network of suppliers, customers and consulting services. The majority of these businesses are family-owned, created with minimal starting capital and located in premises that are often also their place of residence. The commercial sector is the largest, accounting for almost 60% of local businesses, compared to 30% for the service sector and 10% for the industrial sector. The success of small businesses lies mainly in their proximity, trust and personalized attention to customers.

Figure 4: Local businesses in Medellin’s Comunas 1 and 2.

Source: Camille Reiss, 2017.

Figure 5: Business at the bottom of stairs, Medellin’s comunas 1 and 2.

Source: Camille Reiss, 2017.

The proliferation of these small businesses in the city's underprivileged neighbourhoods is due to the fact that they are as profitable or even more profitable than those located in more valued areas in the center and south of the city. 15 Saskia Sassen demonstrates the economic interactions and interdependencies that exist between the city’s global and informal economies. There are indeed connections between these two sectors, when the industries of the global economy need the wide range of industrial services produced by the informal economy, which remains easily accessible because it is located close to the more valued areas (for example, products made in small metal workshops from the processing industry). In this regard, informal settlements, which have grown on unoccupied sites located near the job-generating areas (here, the central and southern zones of the city), are now in a “central” position, compared to the residential peripheries that emerged during the population and urban growth of the late 20th century.

As a result, businesses located in the informal settlements of Medellin benefit from their proximity to the center and south of the city (facilitated by the arrival of the Metrocable), competing with those located in the José Maria Córdova 16 airport's free zone that were forced to relocate from the center due to too much land pressure. This may explain why the industrial sector, although the least represented, has seen the largest increase in the number of companies in comunas 1 and 2 between 2004 and 2009.

Finally, it can be estimated that the local economic development policy of the PUI has had a positive impact on Medellin’s overall economy, if we look at the evolution of the indicators between 2001 and 2011. Indeed, the city's economic growth rate increased from 0.6% to 4.7%; the average per-person income increased from US$298 to US$458; and the proportion of people living below the poverty line dropped significantly from 52% to 22%. 17

By recognizing that it was no longer possible to fight the informalization of the city's economy (50% of Medellin's labour force worked in the informal sector in 2010 18), the municipality was able to transform this phenomenon into a vector of economic development, beneficial to all inhabitants in the city. This has strengthened the economic independence of comunas 1 and 2 and minimized the need for people to travel to the center and south of the city where all the opportunities were previously concentrated.

The inhabitants now want the policies that were started under the PUI to be continued, claiming it is necessary to establish more infrastructure, social housing, vocational training, cultural activities and schools. Indeed, they point out that there is still uneven access to running water and electricity and that living conditions remain precarious for some in terms of housing, employment, education, etc. A more “spontaneous” sense of autonomy seems to have emerged, emanating from a specific representation of the right to “their” city. After all, to which city does the state’s infrastructure actually give access to? Is the fact that public policies have recognized an interdependence between mobility and the right to the city really guaranteeing more egalitarian living conditions, considering that working and residing within the same neighbourhood is a contributing factor to people’s quality of life?

Against the injunction to mobility, the right to immobility

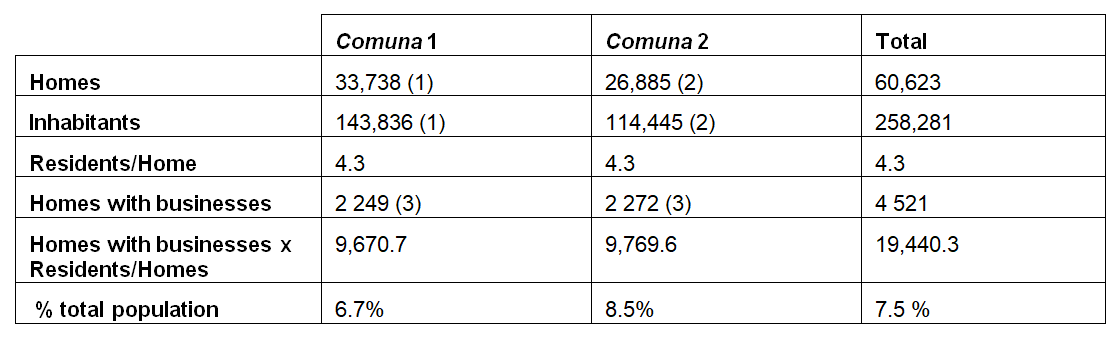

In order to assess the relevance of this approach, it was necessary to estimate the percentage of the population that depended on the local economy of comunas 1 and 2. Based on the premise that home-based businesses allow all family members to be financially self-sufficient, our calculations show that nearly 19,440 inhabitants (or 7.5% of the total population) are financially dependent on these local businesses (Table 1). This means that nearly 20,000 people live and work within their neighbourhood and do not depend on any means of transportation, other than walking, to get to their workplace. This figure would be even greater if we consider the inhabitants who work in non-family businesses within the community, such as supermarkets or commercial spaces dedicated to major brands in telecommunications and appliances, for example.

Table 1: Number of households with a business and number of beneficiary inhabitants, comunas 1 and 2.

Source: (1) SISBEN, 2011a 19 and (2) SISBEN, 2011b 20; (3) DAVILA D. Julio, 2013, p. 96. 21By living and working in their neighbourhoods, we observe that a significant part of the inhabitants of comunas 1 and 2 limit their movements to internal mobility in their community, despite the development of a dedicated transport network 22. What could be seen as a form of “imposed” immobility is considered here as an added value that improves the inhabitants’ quality of life. As one of them points out: “What good would the Metrocable be for me, since I work next to where I live?” Locals are clearly calling for the revitalization of territories newly served by transport: “We need more jobs, social housing, activities and training for young people." Because “staying and living in the neighbourhood is a bet on the future. Even if there are problems, I’m staying because there is a lot of potential.”

The urban intervention of the state has thus stimulated socio-political consciences, especially among young people, who engage and create associations to influence the future of their community 23. The investment and commitment of inhabitants within their neighbourhood reveals their attachment to them. And if they defend the interests and values of their territory, it is because most of them have always lived there, for several generations. But they also like it for a host of other reasons: for its proximity to the center, which facilitates access to the city's opportunities (in terms of employment, education, health, culture and leisure); for the community spirit and support that exists there and gives rise to self-organizing systems that govern sectors as important as transportation or the economy; for its topographical complexity that renders its streets and alleys pedestrian, and the charm of its sloping landscapes that offer panoramic views of the rest of the city. The residents speak fondly about it: “I love my neighbourhood because it is central” 24; “I've lived here for 44 years, everyone knows me.”

Figure 6: Sloping landscape of Comunas 1 and 2 in Medellin.

Source: Camille Reiss, 2017.This is a set of factors that respond to aspirations and practices that are specific to how they live, move and coexist together. Living in an informal neighbourhood would therefore not only result from a series of constraints, but from a choice linked to a specific urban lifestyle, common to other countries in the South. This observation is based on the results of a survey conducted by the Municipality of Medellin, revealing that the inhabitants of stratum 1 (northern neighborhoods) and stratum 6 25 (southern neighborhoods) assess their living conditions similarly: indeed, 54% and 58% of these populations respectively estimate their living conditions to be "good" - even though they have a 20-point gap in their quality of life index. 26

Conclusion

Medellin seems to have found the right balance in its quest to integrate informal settlements, between necessary state intervention for the implementation of infrastructure projects and public services related to employment, education, transport, culture and leisure, and respect for the internal and inherent dynamics of these specific territories. With the establishment of urban infrastructure and services of similar quality to those in the “official” city, as well as greater accessibility between the northern districts and the valued areas of the center and south of the city, all inhabitants feel like they belong to the same city: indeed, inhabitants of northern areas will now say they live in a neighbourhood of Medellin, without specifying that it is or used to be an informal neighborhood.

The government also supported the local economic initiatives of these territories, seen as a potential vector of dynamism in the city's overall economy, believing that the increase in productivity of micro-businesses had the effect of producing more wealth and thus reducing poverty. Driven by a desire to decentralize the city’s economic management, this strategy also appeared to be beneficial from a mobility and environmental standpoint, insofar as by promoting opportunities to work and live within the same neighborhood (comunas 1 and 2), the demand for mobility, as well as greenhouse gas emissions from transport, have been stabilized.

Rather than fighting the informalization of the economy, the government gave inhabitants more options, whether in terms of mobility or jobs. Residents can now enjoy a right to “their” city, whether it’s by choosing to stay in their neighbourhood while taking advantage of the “official” city’s opportunities as they have been made more accessible by the cable car, or by continuing a professional activity that they had already developed for many years (or by creating a new one).

For some, the “informal city” would not exist without the official city. But informal settlements show a degree of autonomy in their functioning, especially in economic terms. The lack of public infrastructure and equipment has in fact always been counterbalanced by the establishment of self-organizing systems, which continue to stucture and manage these territories today. The gains generated by the informal economy represent an important source of income for the inhabitants, and the associative fabric is still very strong in these territories.

So, is it not possible to imagine that it’s the right to immobility, and not the right to mobility, that guarantees the right to “their” city? What if the integration of informal settlements didn’t imply more and more mobility, but rather the recognition of their existence as a specific urban entity, that is an essential component of the fragmented landscape of contemporary cities? It would then be a question of valuing and strengthening their complementary character with the other entities that make up the city, reflecting the many choices and lifestyles of those who live there.

A parallel can be made with suburbs of French cities that were established according to the model of a forced commuting mobility. Now, they seem to be evolving towards greater autonomy. The idea is that, in order to change the city and enhance these terrotories’ potential, it is necessary to put the inhabitants back at the center of public policy. It is therefore a question of initiating strategies aimed at strengthening individual autonomy and the capacity for collective action, by supporting and valuing local initiatives. For while public policies are still necessary at the metropolitan level, alternatives can also be developed the neighborhood level by local populations themselves, to combat discrimination, promote employment and improve the conditions of daily life.

DAVILA D. Julio (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, Columbia, Development Planning Unit, UCL & Faculty of Architecture, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, 2013.

ECHEVERRI R. Alejandro, “A Mobilidade Urbana como indutora dos Projetos Urbanos Integrados (PUIs): O caso de Medellín”, in Sustentabilidade urbana: impactos do desenvolvimento econômico e suas consequências sobre o processo de urbanização em países emergentes. Textos para as discussões da Rio+20 2012I, Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Ministério das Cidades, Mobilidade urbana vol. 1, Brasília, 2015, pp. 78-108.

NAME Leo and FREIRE-MEDEIROS Bianca, “Teleféricos na paisagem da “favela” latino-americana: mobilidades e colonialidades”, GOT, Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, n.º 11, Bianca, June 2017, pp. 263-282.

RESENDE FERNANDES Jose Leandro, “O advento de um estado desenvolvimentista local em Medellín-Colômbia e inferências em seu desenvolvimento econômico”, Anals of the International Seminary Séminiare on Regional Development, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, September 2017.

SASSEN Saskia, “Topographies urbaines fragmentées et interconnexions sous-jacentes”, in NAVEZ-BOUCHANINE Françoise (dir.), La fragmentation en question. Des villes entre fragmentation spatiale et fragmentation sociale ?, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2002.

URBAM EAFIT, Modelo de transformación urbana. Proyecto Urbano Integral – PUI – en la zona nororiental. Consolidación Habitacional en la Quebrada Juna Bobo, Alcalde Medellín, 2013.

Official documents

ALCADIA DE MEDELLÍN, “Medellín en cifras. Número 1”, Observatorio de Políticas Públicas, avril 2011.

DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE PLANEACIÓN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 1. Encuesta de calidad de Vida”, Medellín, 2011a.

DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE PLANEACIÓN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 2. Encuesta de calidad de Vida”, Medellín, 2010.

DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE PLANEACIÓN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 3. Encuesta de calidad de Vida”, Medellín, 2011b.

DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO DE PLANEACIÓN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 6. Encuesta de calidad de Vida”, Medellín, 2011c.

POMA, Urbanway, brochure available for download online, June 2015.

SISBEN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Comuna 1 Popular”, Medellin Prefecture, June 2011a.

SISBEN, “Perfil Socioeconómico Comuna 2 Santa Cruz”, Medellin Prefecture, June 2011b.

1 Modelo de transformación urbana. Proyecto Urbano Integral – PUI – en la zona nororiental. Consolidación Habitacional en la Quebrada Juna Bobo, Alcalde Medellín, EDU, AFD, Universidad EAFIT, 2013, p. 32.

2 The city of Medellin is organized into six zones, each containing several comunas which are further subdivided into neighborhoods. The city has 16 comunas and 175 neighborhoods in total.

3 Alejandro R. Echeverri, ”A Mobilidade Urbana como indutora dos Projetos Urbanos Integrados (PUIs): O caso de Medellín,” in Sustentabilidade urbana: impactos do desenvolvimento econômico e suas consequências sobre o processo de urbanização em países emergentes. Textos para as discussões da Rio+20 2012I, Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Ministério das Cidades, Mobilidade urbana vol. 1, Brasília, 2015, p. 84.

4 Extracts from a series of interviews conducted by the author with the inhabitants of Comunas 1 and 2, from September 18 to 22, 2017, translated by the author.

5 Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, Development Planning Unit, UCL & Faculty of Architecture, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, 2013, p. 100 ; Municipio de Medellín, Subdirección de Metro información, Observatorio del Suelo y del Mercado Inmobiliario (OSMI).

6 Alejandro R. Echeverri, ”A Mobilidade Urbana como indutora dos Projetos Urbanos Integrados (PUIs): O caso de Medellín,” in Sustentabilidade urbana: impactos do desenvolvimento econômico e suas consequências sobre o processo de urbanização em países emergentes. Textos para as discussões da Rio+20 2012I, Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Ministério das Cidades, Mobilidade urbana vol. 1, Brasília, 2015, p. 99.

7 Ibid., p. 93.

8 Ibid, p. 84.

9 Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, op. cit., p. 49-50.

10 Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, op. cit., p. 90.

11 Jose Leandro Resende Fernandes, ”O advento de um estado desenvolvimentista local em Medellín-Colômbia e inferências em seu desenvolvimento econômico”, Annales du Séminaire international sur le développement régional, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, September 2017, p. 15.

12 Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, op. cit., p. 89.

13 Ibid.,p. 80 et 96.

14 Figures calculated from the data published in Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, op.cit., p. 96.

15 Saskia Sassen, ”Topographies urbaines fragmentées et interconnexions sous-jacentes,” in Françoise Navez-Bouchanine (dir.), La fragmentation en question. Des villes entre fragmentation spatiale et fragmentation sociale ?, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2002.

16 Located 800 meters above the Aburrá valley in the East of the city.

17 Jose Leandro Resende Fernandes, « O advento de um estado desenvolvimentista local em Medellín-Colômbia e inferências em seu desenvolvimento econômico », Annales du Séminiare International sur le Développement Régional, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brésil, Septembre 2017, p. 16-17.

18 Alcadia de Medellín, “Medellín en cifras. Número 1”, Observatorio de Políticas Públicas, Apris 2011, p. 54.

19 SISBEN, « Perfil Socioeconómico Comuna 1 Popular », Medellín Prefecture, juin 2011a, p. 5.

20 SISBEN, « Perfil Socioeconómico Comuna 2 Santa Cruz », Medellín Prefecture, juin 2011b, p. 3.

21 Julio D. Davila (dir.), Urban Mobility and Poverty: Lessons from Medellín and Soacha, op. cit., p. 96.

22 Observation made by the author from a series of interviews conducted in September 2017 with inhabitants of Medellin’s Comunas 1 and 2.

23 Political, cultural or social actions. See Piedra en el Camino (2017), Mi Comuna 2 (2009), Las Cometas (1996), Con vivamos (1993), among others.

24 Geographical proximity with the center, reinforced by the Metrocable.

25 The population of Medellin is divided into 6 stratas, which are defined according to socio-economic criteria. Stratum 1 represents the poorest segment of the population, and stratum 6 represents the wealthiest segment of the population.

26 Departamento administrativo de planeación, “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 1. Encuesta de calidad de Vida,“ Medellín, 2011a ; “Perfil Socioeconómico Estrato 6. Encuesta de calidad de Vida,“ Medellín, 2011c.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus x

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications