30 September 2021

The residents of Lima in Peru, and Bogotá in Colombia, saw their daily mobilities greatly disrupted during the lockdown that lasted from March to July 2020. As part of the ANR Modural project on sustainable mobility practices, a study was conducted, through family accounts and remote interviews, to examine how individuals and their families were impacted by the lockdown in their professional activities and private lives, as well as the strategies they adopted to cope with it.

Based on the collective experience of the ANR Modural program (2020-2023) on sustainable mobility practices in the working-class outskirts of Lima, Peru and Bogotá, Colombia ( modural.hypotheses.org), 1 the goal of this article is to present how Covid-19 affected daily travel in these two Latin American cities, each of which is home to about 10 million inhabitants. These two cities are also highly spread out and strongly segregated, making transport conditions difficult. Polls show that, due to congestion, pollution and insecurity, daily mobility is the second biggest cause of dissatisfaction, after insecurity. 2 Over the past two decades, however, these cities have promoted a series of measures aiming towards a more sustainable mobility. They have made innovations in public transport, with the implementation of BRTs 3 (the Transmilenio in Bogotá, from 2001, and the Metropolitano in Lima, from 2010; map 1), a metro line in Lima in 2012, an urban cable car in Bogotá in 2018, and buses integrated into the BRT network (the SITP in Bogotá from 2011 and the SIT in Lima from 2012).

Map 1: Lima and Bogotá, the two cities of the Modural program

Both cities have also introduced road space rationing which is governed according to days of the week and the vehicle’s number plate (the pico y placa). This has been in place since the 1990s in Bogotá and since 2019 in Lima. Despite these advances, individual motorised transport (cars, taxis, motorbikes), which causes heavy pollution, keeps growing and the shift to more sustainable modes, such as public transport, walking or cycling, remains limited, especially in peripheral sectors. Yet, cycling has been promoted since the 1970s in Bogotá and to a lesser extent since the 1980s in Lima (Montero, 2017). According to the latest mobility surveys, 4 the modal share of cycling was barely 1% of daily trips in Lima in 2012 and only 6% in Bogotá in 2019.

As of March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted people’s living conditions, lifestyles and daily mobility, both in Lima and Bogotá. It has also impacted how we conduct our research, by limiting our researchers’ ability to travel internationally and conduct field work on location. 5 These disruptions led us to reevaluate the original objectives of the Modural project, even if the original goal remains: to understand the mobility practices of those living in the working-class outskirts, from a sustainability standpoint.

In this article, we focus on the tactics and strategies deployed by residents to deal with the crisis, focusing on the most intense period of the first lockdown from March to July 2020. We continue this analysis by integrating subsequent observations, in particular questioning the sustainability of the observed changes: the sudden drop in travel, the dissatisfaction with public transport, the shift towards individual transport modes (whether motorised or not). Our approach focuses on an aspect that has so far been largely ignored by the media, 6 namely the disruptions that individuals and households have experienced in their professional activities and private lives due to the health crisis, but also the strategies adopted to deal with its effects.

The Covid epidemic caused an unprecedented upheaval in lifestyles and daily mobility practices: people were forced into lockdown in uncomfortable and overcrowded living spaces in working-class neighbourhoods, schools were closed, public transport ran on quotas, use of individual vehicles was restricted, and businesses had to reduce their activity, leading to a general slowdown of the urban economy. At the start of the pandemic, strict lockdown measures and travel restrictions were imposed, resulting in forced immobility and necessary modal shifts. In March 2020, the use of private vehicles was banned for almost four months in both cities. Meanwhile, public transport capacity was halved for two months, before a gradual recovery. The number of passengers decreased by more than 80% during the first lockdown. Numbers have still not returned to pre-pandemic levels, with only half the number of travellers as at the end of 2020 in both cities. Six months later, in August 2021, the number of passengers was still 23% lower in Bogotá and 43% lower in Lima, according to IDB data. 7

With the health crisis, “tactical urban planning” initiatives - notably “corona cycleways” 8 - focused attention and opened the debate on how the crisis could be an opportunity to change the existing mobility model. In this respect, the city of Bogotá has distinguished itself internationally, with an ambitious program of temporary bicycle lanes, initiated four days before the March 2020 lockdown, to fight again the spread of the virus and to limit transportation congestion: 117 km of lanes were installed on March 17, to which 45 km were added a month later 9. These 162 km were a maximum that was then gradually reduced. A first adjustment resulted in a network reduced to 82 km in April 2020 (map 2 and photos 1). From the end of August 2020, other temporary lanes were either removed or transformed into permanent lanes, leaving a 36-kilometer-long network of temporary tracks in June 2021.

In Lima, the implementation of measures was slower and more limited in scope (in September 2021, only 46 km had been set up or were being installed 10), however the authorities did indeed integrate cycling into their projects, with the launch of a plan that will ultimately be comprised of 300 km of cycleways. However, progress remains limited as of today (September 2021).

Map 2: Temporary bike lanes in Bogotá (by M. Lucas, 2021). Spring: Secretaría de Movilidad de Bogotá. The map shows the existing network in April 2020 (82 kilometers).

Cyclists on the Septima in Bogota, 01/10/2020, Carlos Felipe Pardo

Waste pickers, Deliverys and cyclists in Bogota, 27/06/2020, Carlos Felipe Pardo

Bike repairers in Bogota, 27/06/2020, Carlos Felipe Pardo

Temporary bicycle lanes in downtown Bogota, next to the SITP, 04/08/2020, Carlos Felipe Pardo

Pistes cyclables temporaires à Lima, 06/2021, Metropolitan Municipality of Lima

Conflicts of use on Lima's bicycle lanes, 06/2021, Public Group Facebook “Lima en bici”

In both cities, disruptions were particularly severe in working-class neighbourhoods on the outskirts, where the contagion rate was highest, 11 and where government-imposed travel restrictions were more difficult to cope with than elsewhere (Vega Centeno et al., 2021). 12

The health crisis exacerbated job insecurity. Informal work, which is widespread in these cities and omnipresent in the peripheries, was strongly impacted by the crisis. It became harder to make a living and many people had to work less or lost their jobs. Domestic workers, street vendors, construction workers and delivery men were among the many jobs where teleworking was not really an option. As a result, many people were faced with the dilemma of “going out to work or starving to death." This was one fundamental difference with the situations we observed in Europe. 13

The use of public transport - which was often taken out of necessity - increased the risk of contagion 14 due to overcrowding in buses (despite health protocols and reduced capacity) and also at interchanges. - People coming from the poorer outskirts pass through these up to 6 times per trip in both cities. In Huaycán – the district of Lima we studied – nearly 44,000 people commute outwards every day for work (compared to 17,000 people who commute into Huayác for work, which equates to a negative balance of 26,000 people, as shown on Map 3). South of Bogotá, in the poorest part of the city, this figure rises to 17,000 commuters from Altos de Cazucá, and 30,000 from El Lucero (two of the research areas of the Modural program), which were among the most affected by the pandemic. 15 In these neighbourhoods, the reduced income forced households to live day-to-day, buying groceries daily in local markets which then became major Covid hotspots. 16 Travel conditions also deteriorated. Travel costs increased overall, either because of the increased price of informal transport such as collective taxis, motorcycle taxis or “combis,” 17 especially in Lima; or because of the use of more expensive alternatives, in particular taxis and chauffeured vehicles (Uber and others).

Map 3: Balance of inflows and outflows in Lima (in the morning, for work reasons) (by F. Demoraes)

Sources: EOD 2012 and INEI.

Made by: F. Demoraes, Modural 2020.

Map 3 shows the balance of trips to work before 10 am. In blue are the mainly residential areas (including Huaycán, delimited in green on the map), which have a negative balance, that is to say that there are more people leaving than arriving. Conversely, the areas in red represent the main employment centres.

To understand these realities, at a time when field trips were almost impossible, the Modural team experimented with several data collecting methods. Here, we provide the preliminary results of two of them: 36 “family accounts” carried out in Bogotá by students at the University of Santo Tomás in September 2020, and 10 individual interviews, conducted remotely between October and November 2020 in Huaycán, a working-class neighbourhood on the outskirts of Lima (shown on maps 1 and 3). Both methods were implemented when the two cities were emerging from a long period of general lockdown, which ran from March to July 2020, and was further extended in Bogotá with a district-based rotating lockdown until August 2020, and in Lima with a curfew. These two collection methods allowed us to document the impacts and strategies implemented by the inhabitants during this time, and to differentiate the periods before, during, and after the lockdown.

The goal of the “family accounts” was to understand how Covid-19 impacted the family unit, not just the individual. Indeed, we know that the crisis led to readjustments that took place interdependently within households, impacting everyone's activities and forcing families to adjust their usual care habits. 18 To conduct this study, we took advantage of the continuing links between the research professors of the Modural program and their students, by asking the latter (as part of their training) to ask family members living with them a set of questions. This method has limitations in that it didn’t allow us to specifically target the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods, as these students on the whole belonged to the middle classes. 19 The living standards of the different neighbourhoods are shown on Map 4, together with the approximate locations of the students who took part in the study. However, this method did allow us to capture a variety of situations, and to collect data that would otherwise have been difficult to obtain (Table 1).

Description of family accounts in Bogotá

36 accounts, 149 individuals.

Members per household: 4 on average; 1 minimum; 8 maximum.

Accounts in the most disadvantaged sectors: 4 of 36 .

Map 4: Places of residence of the students who took part in the family accounts and percentage of poorest households by sector (Social Condition Index 1 and 2), 20 Bogotá 2020. Reading aid: the areas in dark red are the most disadvantaged. NB: for confidentiality, the pins show the approximate location of where the students live.

Regarding the individual interviews conducted in Huaycán, we used contacts made through a previous study (sociology thesis by Jimena Ñiquén, 21 recruited as part of the Modural program to carry out interviews), and we proceeded by snowball sampling. The ten people who were interviewed came from lower social classes than the students involved in the family accounts carried out in Bogotá. 22 However, they were not representative of the most difficult situations within Huaycán, because remote data collection made it difficult to reach people living in the poorest outskirts. For the 10 interviews conducted, internet access was an obstacle: none included video, with the vast majority done by phone, and in some cases via WhatsApp.

Description of the interviews conducted in Lima

5 women / 5 men

Area of residence in Huaycán: consolidated or in the process of consolidation (not in the extreme periphery)

4 youth (18 to 29 years old)

6 adults (30 to 59 years old)

1 student; 2 students/workers; 5 formal workers; 2 informal workers

This interview method limited the interactions with the respondent, making it impossible to capture elements of non-verbal communication. But despite these difficulties, the information collected represents an original body of data on the inhabitants’ experience of the health crisis.

While the Covid-19 crisis undoubtedly affected the daily activities of all household members (spouses, parents, children and others), it did so in different ways. Through the 36 accounts we obtained, we tried to understand what arrangements the families implemented to adapt to the situation. The idea was therefore to observe each member’s strategies with regards to their mobility, work or studies, and also to understand the possible residential relocations and reorganisations of daily life, all through the prism of the family.

She begins like this: "The Covid 19 pandemic transformed our lives, our social relationships, our jobs, our forms of mobility, or to put it another way, right down to the last grain of sand in the sea."

Alexia lives with her father in a house in a residential area. Her mother lives elsewhere, in an apartment, with her 6-year-old brother. The father, 53, works in a civil construction company north of Bogotá. Her mother, 43, runs a shoe shop in a shopping mall. Before the pandemic, both parents used public transport to go to work, as did Alexia to go to university. The little brother walked to school.

At the start of the pandemic, the mother, little brother and a female cousin moved into the father's house, in order to be closer to the mother's workplace. They stayed there until the end of August 2020 (6 months). Her parents were put on mandatory leave. Soon after, her mother's company offered her voluntary redundancy with a severance package, or for her to go on unpaid leave with the promise of a return to work once the lockdown was over. She took the second option and in May, she resumed work at the request of her company, breaking the lockdown rules in the process. She started doing online sales, while making a few trips to her store, always by public transport. After a month, the father started working again, remotely for two weeks at first, then in a hybrid way with occasional trips to sites requiring a special permit. He continued to use public transport. A localised lockdown twice forced him to go back to teleworking.

Alexia looked for work to help her family, but to no avail. She then decided to launch a website to sell used books. She was the one who took care of her brother's school activities, with guides sent by the school and sometimes with the help of her cousin. Her father managed to find one more computer. Alexia, her brother and her cousin stopped going out, except when the cousin went out to do the shopping. She took care of the household chores. She used to do so at her mother's house and continued to do so during the lockdown, but it took her more time. While before the pandemic “everyone got on with their own lives, minding their own business,” the lockdown changed everything, increasing the forms of interdependencies between household members: "All aspects of everyday life, for me and for my family, have changed."

Our survey revealed two main impacts on daily life: the forced reduction of travel due to lockdown measures, and the economic problems (explicitly mentioned in 14 cases) related to the decreased incomes of household members.

In 14 accounts, we also saw changes of residence at the beginning of the lockdown. Some students (2) left Bogotá, where they had come to study, to return to their families. For others (5) it was more complicated: some remained stranded in other cities throughout the country, where they were passing through when the lockdown started, while another moved near his internship to avoid exposing his family, who remained in Bogotá, to the virus. We also saw changes of residence within Bogotá: four students moved to a different area to be closer to work, or to stay with their parents. And in the last three cases, other family members joined them in their homes, as in Alexia's family (in the box above), for economic reasons (saving rent) or to help take care of more vulnerable people.

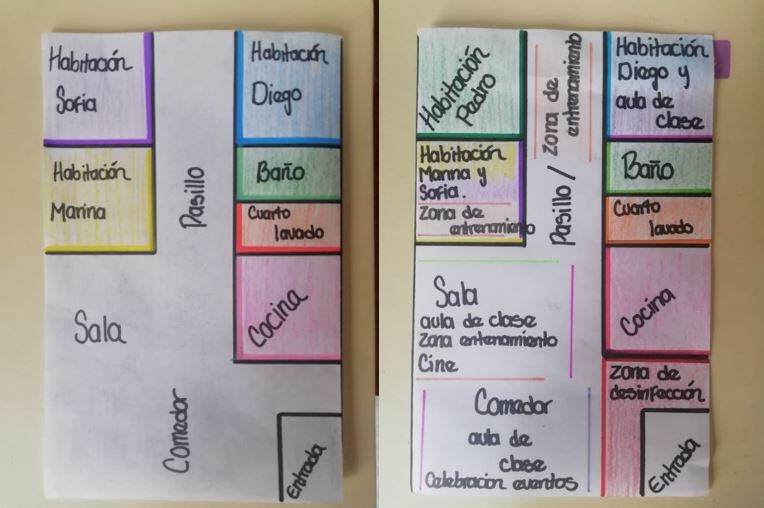

Inside the home, 24 the space was also reorganised: the bedroom became a virtual classroom, as did, sometimes, the terrace. Others set up their desks under the window, to get some natural light and thus limit the electricity bill. This is the case of Leslie (Figure 1):

"I turned my brother's bedroom into a classroom and occasionally had breakfast or meals there, and sometimes it was the living room or my mother’s bedroom that became my university workplace.”

Figure 1: The organisation of Leslie's home before the pandemic and how it was reorganised during lockdown (C13).

Left image: Habitación: bedroom; Sala comedor: living room – dining room; Cocina: kitchen; Pasillo: corridor; Baño: bathroom (with toilet); Cuarto lavado: laundry room; Entrada: entrance. Right image: Zona de entrenamiento: exercise area; Aula de clase: classroom; Cine: cinema; Celebración evento: celebration of events; Zona de desinfección: disinfection area.

All students undertook their courses remotely. For their families, work was reorganised in different ways. 30 people opted for telework (mainly executives, managers and people working in education), 20 were allowed to go to work because their work was considered essential (3 did so without authorisation), 3 others alternated between working on-site and teleworking. 7 people lost their job; 7 others wre made temporarily redundant; 5 were forced to take time off. 13 people changed jobs because of job loss or switching fields, while 2 others looked for work, unsuccessfully. In the end, 30 out of 36 households had at least one family member that was impacted professionally, by a more or less temporary change or loss of activity.

The case of Luciana's brother (C9) also illustrates the uncertainty of this period:

“He changed departments within the company. [...] He switched to teleworking, with a 20% pay cut for four months. Those who volunteered were then able to return to on-site work, with their initial salary restored. [But] he was fired after six months and is now looking for work.”

Daily commuting decreased drastically in March. Of the 149 individuals surveyed, 50 remained at home, sometimes for the duration of the lockdown. For those who chose or were forced to move, walking was the preferred mode (16 individuals), often for short trips or to go shopping. People were afraid of the bus and of the Transmilenio, even though they still saw it as necessary (9 cases). Six people opted for taxis, especially via platforms like Uber or Beat. Twenty two continued driving their personal vehicles. Eleven rode a bicycle. Some had already done so before, others started using it now or made it their main mode of transport. This was the case of Leslie's father (C13):

“He changed how he travelled, switching from his car and public transport to riding a bike.”

it was the same for Josefina's mother (C21):

“She constantly had to move, by changing her mode of transport, from the SITP to a bicycle. The goal was to reduce the risk of contagion, but it also reduced her spending on public transport. That's why it became her permanent mode of transport.”

Changes in travel habits were often determined by how individual professional or educational activities were reorganised. Beyond the rise of cycling and walking for short trips, there was an overall decrease in the number of trips, mainly to protect other members of the household, especially the elderly. 25

Internal dynamics and routines within the household were also disrupted. Household tasks were distributed in new ways and the time spent on them increased. Most care and housekeeping activities were carried out by women (especially mothers, but also grandmothers and daughters). Conversely, it was men, especially young men, who went out to do the shopping.

The lockdown thus created a new state of affairs: children staying inside and studying at home due to schools being closed; parents teleworking, prevented from working, or instead forced to spend more time away from home to make up for lost income; consumption habits were also disrupted, as was the support that was previously given to the elderly or vulnerable parents, living in the home or elsewhere. This was the case, for example, of Mrs González, who runs a small business in the tourism sector. Her daughter explains (C14):

“The health crisis radically changed her daily work. [...] Household chores increased. [...] Because we live in the same housing estate as my grandparents, my mother went to see them every day, to take care of them, to keep them company, to prepare lunch and dinner, among other things.”

This increased burden on women is worth highlighting, as it runs counter to a trend towards greater emancipation observed in previous years: further studies will undoubtedly be needed after the health crisis to see if this was simply a by-product of events or or a more fundamental trend.

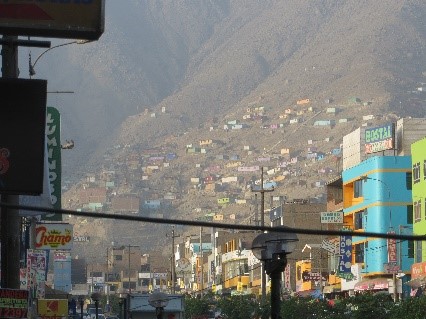

Ten interviews were conducted in Huaycán, one of the Modural project’s survey areas, selected because the socio-economic and mobility conditions are particularly difficult there. 26 The Huaycán neighbourhood is located on the eastern outskirts of the Peruvian capital (Map 2). It has a population of nearly 150,000, more than 50% of whom have a low socio-economic level. Urbanisation extends over steep hills. Informal transport is omnipresent; no mass public transport service is available nearby.

[[{"type":"media","fid":"4765","attributes":{"typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"428","height":"321","alt":"lima perou huyacan"},"view_mode":"default"}]]

Photos 2: the Huaycán district: spontaneous urbanisations on the slopes, motorcycle taxis and combis, the main avenue at the foot of the district. Source: “Te Amo Huaycán” Albums on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/136075830@N02/albums

For everyone, mobility was reduced, as transport was synonymous with the risk of contagion. But for many, it remained a necessity, to move around and to get to work, in order to “move forward” (salir adelante). People had to change their routines. Some opted for taxis or motorcycle taxis. Others began to get up earlier in the morning, to catch a bus with fewer passengers, or, if it was full, to wait for the next one. They also changed their habits inside the buses: sitting at the front, not eating on the way, or not sleeping during the trip to stay alert.

As Jimena, a 20-year-old student (E6), says:

"Sometimes before I would leave early, try to save time by leaving without eating, and I would eat on the way and finish sleeping [on the bus], but now you can't sleep, you have to be very careful not to bump into other people, keep distances and all that. [...] You can't eat on the way either, otherwise people look at you as if they want to tell you that it's forbidden, that we're in the middle of a pandemic, that we can't eat here, so you start to think it's out of place, you see? Yet before it was common.”

In general, mobility has diminished with the crisis. The closest geographical contacts were maintained within the family, while those with more distant relatives lapsed. Shopping for food and essentials was carried out mainly in the neighbourhood. Such trips were spaced out as much as possible, and no longer made on the way back from work, like before.

Then quite quickly, buses began to fill up again, with crowds gathering at bus stops. Among the changes observed, bus fares increased, while offers for half-price short trips declined. Motorcycle taxis also increased their rates. Thereafter, people continued to wear masks.

Diego, a 24-year-old student working in construction (E1), says:

“At the beginning, at the very beginning, we started going out in this area and there weren't many people, but now there are a lot of people, in fact it's as if the situation was normal. The only thing missing for this to be normal is for people to stop wearing masks. [...] Yes, there are many people at the stops and in the combis, 27 they’re packed and they keep taking passengers, and on top of that they started to charge more, but in the end, we stopped arguing about it.”

Here as in Bogotá, the economic impact of the pandemic was critical. The jobs people had before the crisis played a key role in their ability to cope with the uncertainty and overall reduction in income. Based on the 10 interviews we conducted, we identified three main profiles, depending on the person’s degree of vulnerability.

The first profile relates to individuals who were moderately impacted: they continued working (especially when their work was considered essential by the authorities), or they were able to switch to teleworking, or they had some savings, or they were supported by another member of the household. During the crisis, they limited their trips, only going out to buy essentials and possibly visit relatives. The second profile corresponds to people who were strongly impacted: their work lost its profitability, but was still maintained. This includes, for example, taxi drivers or small business owners. They had savings. In some cases, the retirement pension of an elderly person sharing their household became the only stable source of income. Often, they had to adapt their economic activity to limit the risk of contagion. They travelled less often and especially less far, for their work and to go shopping.

The third profile corresponds to the people who were hit the hardest: their work became very complicated - sometimes prohibited for street vendors - and when it could be maintained, it involved high risks of contagion. Many were no longer able to work or lost their jobs. They had no significant savings and no alternative support. Many started a new activity: selling various products, providing home delivery services, or driving taxis or motorcycle taxis. Their movements changed accordingly. Some developed a local activity, while others had to travel further to survive.

José, taxi driver, 47 years old (E4):

“The main problem with the pandemic is the economic situation. [...] As I told you, there are many people who have gone bankrupt, others who’ve gone out to work, in order to put food on the table. They were forced to do what they feared all their lives. They were forced to do things they never imagined. [...] I have friends, for example, who started selling marcianos, 28 selling facemasks, selling chicha 29; they managed as best they could.”

Mobility, which has always been a safe sector offering informal jobs in times of crisis, then became their main source of income. This was the case of Renato, a 39-year-old handyman in construction who also drove a motorcycle taxi service, and who wants to buy a car (E9):

“Well, my goal for the future, I want to settle all my debts. My dream is to be able to buy a car, yes a car, for work.” 30

This is also the case for Daniel, a 38-year-old physical education teacher, who decided to buy a motorcycle taxi. He learned to drive, gained his license and now manages to generate about half of his pre-pandemic income.

We saw the emergence in Huaycán of home delivery services, on foot, and sometimes by bike, motorcycle or motorcycle taxi. These small local businesses are replacing the “Rappi” or “Glovo” services, found mainly in the central districts and which weren’t really present in Huaycán before the pandemic. While the working-class peripheries are highly dependent on the city centre for employment, a new neighbourhood economy seems to have developed.

Our study offers an original insight into the impact of the health crisis on mobility and daily life in Bogotá and Lima, but also on how to think about the transition to a more sustainable mobility.

In terms of policies first of all, the lockdown and mobility restriction measures, in particular those implemented during the first months of the crisis (from March to July 2020) and later renewed during the second peak in infections (early 2021), have forced a complete transformation of mobility practices. In both cities, the use of individual vehicles and taxis was severely limited, while public transport ran with reduced capacity. Bogotá distinguished itself with its policy of encouraging the use of bicycles, with the quick implementation of corona cycleways. The authorities in Lima followed suit, albeit belatedly and tentatively. In this context of drastic travel reduction, two scenarios gradually emerged: the first, a virtuous one, was a shift towards more sustainable practices such as cycling or walking; the second, a more problematic one, was a boom in individual motorised transport (cars, motorbikes, taxis, app-based vehicles), which are more polluting options and likely to aggravate the problems of urban congestion.

With the volume of travel returning to its pre-pandemic levels by the first half of 2021, we can question whether the measures applied during the crisis can permanently transform mobility practices. On the one hand, cycling seems to be the big winner, with a growing number of cyclists and infrastructure projects, continuing a pre-existing trend. 31 However, the overall outcome remains mixed. In Bogotá, beyond the hype and heavy marketing around cycling, the integration of cyclists remains difficult, 32 and the length of temporary bike lanes has turned out to be quite limited - most had even disappeared by June 2021. In Lima, current projects will certainly compensate for many shortcomings, but there is still a long way to go before cycling becomes widespread, while the incentive policies put in place by the authorities are already being met with various restrictions. As early as June 2021, the Ministry of Transport announced a list of binding rules and new fines for cyclists. 33

Regarding public transport, the drastic drop in passenger numbers weakened the financial stability of service providers, forcing public authorities to intervene with subsidies or loans. Despite limited resources, the service needs to be improved if usage is to pick up again, by integrating health protocols. But the challenges are all the greater given that public transport was already a major source of dissatisfaction before the crisis, with passenger numbers declining on the Transmilenio in Bogotá, mainly due to crowded lines and deteriorating traffic conditions. Furthermore, the use of individual vehicles has only occasionally been questioned. While access to cars remains limited for the poorest members of society, we can expect an increase in motorbike use. Taxis, both formal and informal, as well as Uber-type platforms, also maintain a strong presence.

The underwhelming policies in favour of active mobility in the face of the Covid crisis, as well as the exacerbated vulnerability of public transport, therefore highlight increasing mobility inequalities, rather than a transition towards a more sustainable model. As such, the crisis doesn’t seem to have led to the emergence of an ecological conscience, as we have seen in Europe. 34 This is especially true in the working-class outskirts, where the subsistence of the household remains the top priority, to the detriment of environmental considerations. Employment, which is a necessity and a question of survival, was actually the main reason for protesting the lockdown measures. The working-class outskirts remain dependent on public transport, especially for economic reasons, and have little interest in incentives for active modes, which are more adapted to short journeys and therefore speak more to central districts.

But the issue of transitioning to more sustainable mobilities can also be questioned in light of the inhabitants’ new habits. The lessons drawn from the family accounts and interviews conducted in the two cities clearly show that the impact of the Covid-19 crisis was not limited to health, quantified in the daily number of deaths or new cases announced by the authorities and reported in the press. The pandemic completely changed everyone's daily life and mobility practices, resulting in a reorganisation (at least temporarily) of their living spaces and ways of dwelling. As V. Kaufmann 35 points out, in the European context, we see a return of spatial proximity in everyday life, and this has less to do with the rise of teleworking or new leisure activities than with travel constraints, with measures to mitigate the risk of contagion and the development of new local activities. In a way, this could contribute to the implementation of a more sustainable mobility, by limiting distant trips. But these choices are often constrained, by a fear of the virus, or by the loss of a job, or by the deterioration in learning conditions for young people (when their school or university is closed), or because the individual has stopped taking advantage of the resources of the entire metropolitan area. This dilemma, which is apparent both in the Lima interviews and the Bogotá accounts, is a common challenge for these great cities.

Ultimately, what matters is remembering the reasons and constraints that underpin the mobility restrictions, and questioning their implications for people’s quality of life. We have seen that the impact of the crisis has been further complicated by the fact that it has led to more vulnerable livelihoods and precarious working and learning conditions. The lockdown thereby created a new state of affairs: children staying inside and studying at home; parents teleworking, or prevented from working, or instead forced to spend more time away from home to make up for lost income; consumption habits were disrupted, as was the support that was previously given to the elderly or vulnerable parents, living at home or elsewhere. The restrictions on mobility clashed with the vital need to travel for those who are unable to telework and have to brave the risk of contagion. Surveys conducted in Bogotá and Lima show that these difficulties affected the entire population but reveal that some were more vulnerable than others. Especially the inhabitants of the working-class peripheries without stable employment or whose jobs were compromised by the health crisis (results observed in Lima); as well as households with vulnerable members who require special care (results observed in Bogotá). Faced with these challenges, we identified several strategies: staying at home, reorganising domestic chores, reassigning roles within the household, redefining forms of mutual aid and solidarity, developing entrepreneurship, or providing local services to leverage a new demand.

1 Launched on January 1, 2020, for a period of three years, the Modural program is funded by the National Research Agency (ANR, Agence Nationale de la Recherche) and involves about twenty researchers, in a partnership between Rennes 2 University, the French Institute of Andean Studies, the Catholic University of Peru, and in Colombia, the National Universities, Piloto, Santo Tomás and Tadeo Lozano. The Modural project focuses on the study of individual travel practices, unlike most other research on daily mobility in Latin American cities that primarily focuses on public policies and the modernisation of public transport. By focusing its research on people’s daily commutes to work or school - which represent the majority of trips - its goal is to identify the obstacles and levers that restrict or promote the adoption of more sustainable mobility practices. It seeks to understand the routines, strategies, and contextual elements that influence living practices, from socio-economic constraints and obstacles related to residential localisation, to representations and life stories. It focuses on working class outskirts, which are socio-economically vulnerable, lack transport services and offer poor accessibility to urban centralities (employment, education, and services). What does sustainable mobility mean in these peripheral neighbourhoods, which are often side-lined in debates on the matter? How can we enable their inhabitants to access more sustainable forms of mobility and how would this improve their quality of life?

2 Surveys: Lima Cómo Vamos ( http://www.limacomovamos.org/informesurbanos/) and Bogotá Cómo Vamos ( https://bogotacomovamos.org/encuestas-de-percepcion-ciudadana/).

3 Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT (Bus with high level of service), running on designated lanes.

4 The latest data comes from the Lima JICA Survey in 2012 and the Bogotá Mobility Survey in 2019.

5 Gouëset et al. 2021. “Étudier les mobilités durables dans des villes durablement immobilisées par la covid-19… À propos du programme ANR Modural” [Studying sustainable mobility in cities permanently immobilized by Covid-19... About the ANR Modural program], Palimpseste, N° 5, p. 6-11. ⟨hal-03005287⟩

6 See the Covid-19 report on Modural's Research Notebook: https://modural.hypotheses.org/covid-19

7 https://www.iadb.org/es/topics-effectiveness-improving-lives/coronavirus-impact-dashboard . For a complete study of the chronology of the health crisis and its consequences on daily mobility in Lima and Bogotá, see Robert J., Lucas M., Gouëset V. (forthcoming) “Du confinement à la perspective d’une mobilité plus durable : impacts de la Covid-19 à Lima et Bogotá” [From the lockdown to the prospect of more sustainable mobility: impacts of Covid-19 in Lima and Bogotá], in Boidin-Caravias C., Damasceno Fonseca C., Le Tourneau F-M., Magnan M., Théry H. (Eds.), La Covid 19 et les Amériques : éclairages à chaud [Covid 19 et the Americas: immediate perspectives], Colectivo collection, IHEAL Editions, Chapter 4. The remarks given during the symposium called "A year of Covid-19 in the Americas" (Un an de Covid-19 dans les Amériques), organized by the Institute of the Americas, iGLOBES, Mondes Américains-CRBC, IHEAL-CREDA, in April 2021 ⟨hal-03216322⟩ are available in video online: https://modural.hypotheses.org/1310

8 Cycling lanes which are usually protected, and intitially set up temporarily. The term "corona cycleway" (coronapiste in French) does not exist in Latin America, where people speak rather of “temporary or emerging bike lanes.”

10 https://www.descubrelima.pe/ciclovias/#ciclovias-emergentes

11 For the case of Lima, see Clausen J., Barrantes N. (2020), "¿Cómo se asocian el riesgo multidimensional y los efectos de la COVID-19? Evidencia a nivel distrital para las provincias de Lima y el Callao en Perú.", in Iguíñiz, J., Clausen, J. (Dir.), Covid-19 & crisis de desarrollo humano en América Latina, Instituto deDesarrollo Humano, PUCP, Lima, p. 111-132. For the case of Bogotá, see Laajaj R. et al. (2021), "SARS-CoV-2 Spread, Detection, and Dynamics in a Megacity in Latin America." Documentos CEDE, No. 18, 41 pp. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3822625 .

12 Vega Centeno P., Robert J., Demoraes F., Moreno C., Gouëset V. (2021) (submitted February 2021). "¡Dime dónde vives y te diré cómo te pegó la cuarentena! Formas de habitar e impacto del Covid-19 en Lima y Bogotá", Revista INVI.

13 Vincent Kaufmann (2021), "Lockdown", Mobile Lives Forum. URL: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/lockdown-13664

14 On Lima, see Vega Centeno P., 2021, "Las centralidades de Lima y la movilidad: la organización de la ciudad como factor de vulnerabilidad al COVID-19", in Iguiñiz J., Clausen J., (Eds.), COVID-19 & Crisis de Desarrollo Humano en América Latina, Instituto de Desarrollo Humano, PUCP, Lima, p. 417-432, http://isbn.bnp.gob.pe/catalogo.php?mode=detalle&nt=119388

15 Duque Franco, I. (2020). "Ahondando la brecha. pandemia y desigualdad socio-espacial en Bogotá." Crítica Urbana 3 (15): 23-26.

17 Shared taxis are taxis that run on specific routes and take several passengers. Motorcycle taxis, which are widespread in Lima, are three-wheeled motorcycles with a roof. In Bogotá, they are just classic motorbikes, although they are banned there, so there are fewer. “Combis,” which are common in Lima, are small vans which can seat about fifteen passengers.

18 Care includes a set of activities of mutual aid, support, companionship (intergenerational solidarity, intra-family help, accompanying children and people with disabilities, care for the elderly, etc.) and housekeeping (shopping, etc.).

19 In Bogotá, the middle classes are considered to correspond to households with an income of 2 to 5 times the minimum wage (the monthly minimum wage is equivalent to about 200 euros). They have between 11 and 60 euros per day per person. They represent 55.1% of the population of Bogotá in 2017 (against 35.6% for the working classes, and 9.4% for the upper classes). Source: Fundesarrollo & DANE, 2020.

20 The Social Condition Index is an indicator of households’ position in the social hierarchy. It is calculated by dividing the household’s academic level (average number of years spent studying by people aged 15 and over) by the dwelling’s occupancy (number of people per room). The ICS1 class corresponds to the poorest 10% of households, the ICS2 class to the next 15%.

21 Ñiquén J., 2018, Entre la necesidad y la acumulación. Una aproximación al rol del suelo y la vivienda en los procesos de reproducción y movilidad social de los sectores populares. El caso de las familias fundadoras de Huaycán, Lima; Tesis Sociología PUCP, http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12404/12400

22 In Lima, the working classes correspond to households earning less than 1.2 times the minimum wage (the monthly minimum wage is equivalent to about 200 euros). These two groups represent respectively 6% and 25% of households in Lima according to INEI data in 2020. The middle classes represent 43% of households, the upper middle classes 22% and the upper classes 4%. In Mondural’s 4 survey areas, more than 80% of the census districts are predominantly comprised of working-class households, compared to 60% for the entire city. Source: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2021-01/nse_2020_v2.pdf.

23 For confidentiality reasons, all first and last names have been changed.

24 The vast majority were apartments, hosting an average of 4 people, and up to a maximum of 8. See an illustration of a dwelling in the portrait "The Gomez family’s account of the health crisis.”

25 In Colombia, several generations of a same family often cohabit in the same home, with the elderly in regular contact with the young.

26 See the Modural Project Survey Area Selection Report: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03053354/document

27 Vans used as informal minibuses in Lima.

28 Homemade water ices, with fruit pulp.

29 Traditional homemade corn-based drink.

30 As a taxi, or for deliveries for example.

31 It is estimated that with the health crisis, the modal share of cycling has tripled in both cities: in Bogotá, it went from 6.6% in 2019 (according to the Origne Destination Survey) to 18% in April 2020 and 10% in December, according to data from the Secretaría de Movilidad; while in Lima, it went from 1% according to perception surveys conducted between 2010 and 2019, to 3% in 2020, according to a survey conducted by the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima. See Lucas, M., “La pratique quotidienne du vélo à Bogotá. Le rôle des représentations et l'évolution des profils de cyclistes” [The daily practice of cycling in Bogotá. The role of representations and the evolution of cyclist profiles], 3rd Francophone Meeting on Transport and Mobility, June 3, 2021.

32 See article and video in El Tiempo, 03/09/2020, Carros vs. Bicicletas: un nuevo pulso in Bogotá, https://www.eltiempo.com/bogota/bogota-criticas-por-ciclorruta-de-la-carrera-septima-que-quito-espacio-a-los-carros-535597

33 El Comercio, 17/05/2021, Papeletas para los ciclistas: las claves sobre las multas que empiezan a aplicarse desde el 3 de junio, https://elcomercio.pe/lima/transporte/papeletas-para-ciclistas-las-claves-sobre-las-multas-que-empiezan-a-aplicarse-desde-el-3-de-junio-bicicletas-mtc-reglamento-de-transito-noticia/?ref=ecr

34 Vincent Kaufmann (2021), "Lockdown", Mobile Lives Forum. URL: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/lockdown-13664

35 Vincent Kaufmann (2021), "Lockdown", Mobile Lives Forum. URL: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/lockdown-13664

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xThe lockdown measures implemented throughout 2020 in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, while varying from one country to the next, implied a major restriction on people’s freedom of movement for a given period. Presented as a solution to the spread of the virus, the lockdown impacted local, interregional and international travel. By transforming the spatial and temporal dimensions of people’s lifestyles, the lockdown accelerated a whole series of pre-existing trends, such as the rise of teleworking and teleshopping and the increase in walking and cycling, while also interrupting of long-distance mobility. The ambivalent experiences of the lockdown pave the way for a possible transformation of lifestyles in the future.

En savoir plus xThe remote performance of a salaried activity outside of the company’s premises, at home or in a third place during normal working hours and requiring access to telecommunication tools.

En savoir plus xActive mobility refers to all forms of travel that require human energy (i.e. non-motor) and the physical effort of the person moving. Active mobility occurs via modes themselves referred to as “active,” namely walking and cycling.

En savoir plus xPolicies

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications