New voices 25 October 2021

How do Norwegian environmentalists negotiate their own air travel? Rather than focusing on whether or not flying is justifiable, this thesis regards air travel as a social practice and places the emphasis on what aeromobility means for consumers, why they continue to fly, and how aeromobilities change and become (un)sustainable. The research shows that air-travel is not only a practice in its own right, but part of other practices. The implication of this is that achieving more sustainable mobilities requires attention to both the modes of transport in question and the wider social practices of which different mobilities are part.

New Voices Awards 2021

Thesis title : Flying Through a Perfect Moral Storm. How do Norwegian environmentalists negotiate their aeromobility practices?

Country : Norway

University : University of Oslo

Year : 2019

Research supervisor : Arve Hansen

Until the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted global aviation, we saw a rapid and deeply unsustainable growth in global air-travel. Norwegians have been among the most aeromobile populations in Europe, yet the Norwegian Air Travel Survey (2017) 1 indicated that even environmentally conscious Norwegians are reluctant to reduce their air-travel.

Why? That’s the question I set out to answer in my master’s thesis, entitled Flying Through a Perfect Moral Storm: How do Norwegian environmentalists negotiate their aeromobility practices? Based on in-depth interviews with Norwegian environmentalists, the thesis offers a qualitative investigation into how environmentally-conscious consumers frame and negotiate their air-travel.

Previous research has established that even environmentalists can be – and often are – frequent flyers. Before I started working on the thesis, few of my peers seemed to discuss this kind of environmental dilemma – or, as some would label it, hypocrisy. By the time I finished, however, the environmental consequences of ‘frequent flying’ had already moved from the margins toward the centre of environmental discourse.

Yet this disconnect between what is preached and what is practised is not well understood. Psychological accounts of cognitive dissonance and ‘flying addiction’ take us only halfway there. Attention is often geared towards the motivations of the individual flyer, while the many social, cultural, and material structures that facilitate some mobilities and not others tend to be glossed over.

Looking to move past this impasse, the thesis focuses on how air-travel is socially and structurally embedded into broader activities, as aeromobility. I frame air-travel as a practice in its own right, and aeromobility as part of many broader practices. This approach makes evident the limitations of overly emphasizing the role of individuals in addressing the climate impact of aviation.

The study required a sample of environmentally-conscious consumers. The empirical material consists of in-depth interviews with 13 Norwegian individuals actively engaged in an environmental organization, conceptualized in the thesis as environmentalists. Rather than relying on self-reported ‘green’ consumers, the participants’ work situation was used as a proxy for environmental consciousness: Given their occupations and interest in environmental issues, they were able to consciously reflect on barriers to change in their own air-travel practices. Interviews were carried out before the Covid-19 pandemic.

The reasons for the environmentalists’ aeromobility were many and layered, often boiling down to maintaining social relations with distant friends, relatives, and peers in daily life where time and money were limited resources.

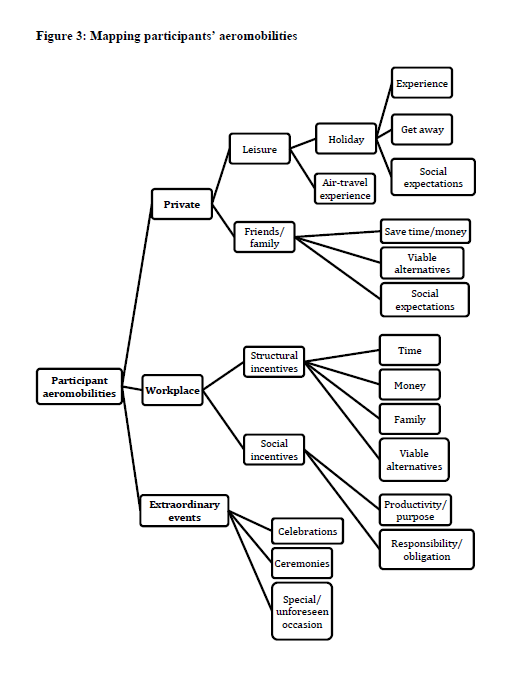

The participants’ air-travel fell into three main categories: private, workplace, and extraordinary travels. These are mapped in the figure below:

In their private lives, participants flew as part of leisure and holidaying practices, as well as for visiting friends and family.

Views on holidays were wide-ranging. For some, flying was thought of as necessary to reach warmer climates or go on adventurous holidays. But others stressed that holidaying did not require aeromobility:

“If I’m going on summer holiday…with some girlfriends, but they wanna go to Thailand and I don’t, then we can’t go together, it sucks, but…then I have to be better at coming up with suggestions, before they do, and then instead of saying no thanks…I say, do you wanna come over to my cabin that weekend?”

While most were willing to forego flights for leisure, being able to access friends and family was important, even if it required flying. Many of the participants had friends and family in Northern Norway, and some in other corners of the world:

“…it’s important to our lives…we have family in India…now there’s a wedding and stuff which makes us feel the need to go there…it’s kind of these things I feel that we…well, if not must do…really really want to do, while cutting out the beach travels in summer…that’s much easier for me…an alternative is maybe to see the family less often, and we’re maybe not willing to do that…we wish to see the family in [Northern Norway as well]…and there are no…viable alternatives [to flying].”

When travelling for work, flying was sometimes understood as the only viable option. Workplace travel was normatively organised in a different way than private travels, where price mattered less, and time mattered more. Through travel, work and leisure were intertwined as longer, lower-carbon journeys could more easily expand working hours and interfere with leisure activities or family duties, creating a ‘time squeeze’.

A female participant admitted that she had opted for plane over train for work travel to free up family time:

“Before I had a family…it was a lot easier – you’re the master of your own time; you do exactly what you want and no-one’s nagging you to do something else, and you can have a good day working on the train, it’s all great, right; when you get a family [there’s] time pressure…in a different way.”

Finally, the participants described a wide range of extraordinary events which required flying. Examples included conferences, concerts, celebrations, and ceremonies where one’s presence was expected in one way or another. Such events – which could range from impromptu weekend trips with friends, to funerals or family situations – were characterized by a sense of relative immediacy, and a lack of thorough planning.

As one participant explained, on the prospect of attending a faraway funeral:

“I think…[sometimes you’re in a] situation where you feel you have to go there, that you can’t think like that, it’s like in the films where the man has a stroke and the wife takes a cab, even though [she] never takes a cab, right; you’re a little, like, in the moment…and then you think, I could’ve taken the train, but I just didn’t want to spend the extra time on the train, I wanted to sit one hour on the plane, and you don’t save a lot of time, but you save a little, and right at that point, it was worth it for me.”

In addition to these, the participants also described specific moments – aptly termed “fuck it” moments by some – in which they abandoned their environmental values and booked flights, for instance to take part in a weekend trip with friends.

These examples illustrate the ways in which aeromobility becomes woven into different practices over which the environmentalists experienced various degrees of control. If we consider the broader social and material context of people’s activities, environmental responsibilities might lose ground to other forms of responsibilities guiding consumers’ mobility practices.

Participants employed different strategies to mitigate emissions from air-travel – including combining travels, adjusting the duration of their stay, flying one way but not the other, or being particularly conscious about consumption choices in the wake of a flight.

Inspired by the commitment to lead a greener lifestyle, actively avoiding flying was nonetheless experienced as a sacrifice requiring perseverance and determination. This encouraged alternative mobility practices and yielded some level of personal gratification, but also frustration – as this quote illustrates:

“…it would actually be fucking wonderful not to care…but unfortunately I, like, care too much…would be nice not to think about it…if flying wasn’t bad for the environment.”

Participants also described the ways in which bypassing aeromobility limited their ability to participate in different practices:

“Not having the opportunity to go [home] very often weighs me down, I don’t have enough free days and [flexible work hours] to justify sitting on the train, to get something out of the weekend.”

The role of aeromobility in participation is well captured in this quote from one participant:

“In theory I wish to fly as little as possible, but I’ve also taken flights I didn’t need to take, like holiday trips, so…it’s a “weighing” between how much pollution I’ve got the conscience to contribute to, and not falling completely outside my society…my friends and family; being able to participate a little.”

In sum, air-travel allows for cheaper, longer, safer, more frequent, and more efficient travels compared to other transport modes. Therefore, it opens up new opportunities for carbon demanding lifestyles and practices, and these in turn fortify aeromobility dependence.

The thesis underscores a notion which has long been influential to mobilities research, namely that mobility is no longer describing merely the process of transport, but an underlying ‘condition’ for modernity. Aeromobility becomes part of the fabric of many people’s lives through aeromobile practices. Therefore, not flying can be challenging – even for environmentalists.

That said, the thesis also provides some hope for alternative mobilities. My findings indicate that train travel has the potential to replace air-travel if and when it fits in with different practices. From a structural perspective, this could be achieved by reducing costs or improving speeds of trains. From a consumer perspective, practices associated with mobility can also be adapted to allow for more time spent travelling. This was evident in the fact that some participants – notably those with flexible schedules and lacking family duties – considered travel to be integral to the holiday practice itself (rather than something which enabled a particular holiday) or by using travel as an opportunity to socialize with friends or colleagues.

As one participant said, alluding to the train journey she had taken from Oslo to Tromsø together with colleagues before Christmas, “You can do it together and make it a social thing”.

The thesis demonstrates that air-travel is not only a means of consumer transport; it is in many ways essential for the experience of mobility in a globalised world where the temporal and spatial dimensions of practices are increasingly expanded. To borrow terminology from geographer Doreen Massey, practices are “speeding up” and “spreading out”.

Keeping up with such changes in lifestyles calls for both faster, longer, and more frequent mobilities, which are facilitated through astoundingly cheap and, until the Covid-19 pandemic, increasingly accessible air-travel.

In terms of theory, the thesis contributes to contemporary understandings of mobility by addressing the embeddedness of mobility in consumers’ lives, and to social practice theory by offering a geographical reading of practices and their dynamic and evolving spatial and temporal boundaries. In the thesis, I have also sought to theorize social practices in a way that acknowledges the practitioner’s capacity to reflect on personal consumption patterns.

Framing aeromobility through the lens of social practice allows us to gain a better understanding of the systemic dimensions of air-travel. Aeromobility does not refer only to the practice of air-travel but also to the broader structures which reproduce this practice, as well as the socio-cultural setting in which flying becomes normalized and expected.

Societal expectations of mobility, the institutionalized rhythms of workweeks and holidays, the dispersal of social ties across geographies, and normative understandings of time-space relations – these are all part of what I term the ‘system’ of aeromobility in the thesis (inspired by John Urry’s influential ‘system of automobility’ 2). Therefore, while air-travel can be thought of as a practice in its own right, the analyses of this thesis have emphasised that it is, perhaps more importantly, part of many other practices with wider social and environmental implications.

Policy wise, the thesis offers some pointers rather than any silver bullet solutions.

Reducing emissions from consumer air-travel requires attention to aviation infrastructure as well as social and cultural understandings of travel and mobility. Attention must therefore be put on these broader practices that may require aeromobility and how they could be performed with less resource-intensive mobility. Crucially, infrastructure should not only guide consumers to engage in sustainable mobility, but also make it easy for those who wish to reduce their environmental footprint from mobility to do so.

Policies should focus on implementing structural changes to mobility systems so that alternative mobilities can more readily be implemented in stubborn consumer practices tied to holidaying and maintaining social relations. In the workplace, promoting and compensating for alternative mobilities – as well as lowering mobility requirements and making use of digital solutions in general – may reduce aeromobility dependency.

The thesis suggests that environmentalism can help sway consumers’ mobility practices – but primarily in a context where this does not involve great personal sacrifice. While downplaying the responsibility of the individual, the thesis does underscore the importance of facilitating broad behavioural change. Though limited in their transformatory potential alone, individuals’ attitudes, awareness, values, and knowledge, are important factors in determining individual responses to potential structural changes or regulations affecting mobility practices.

2021 has been labelled the ‘European Year of Rail’ 3 as new high-speed rails and overnight trains are currently being built across the continent. While these have not reached Norway yet, such commitments to alternative mobility may help guide consumers towards changes in culture and practice.

The thesis has pointed to the ‘double nature’ of aeromobility as both an environmental hazard and an enabler of globalised lifestyles and associated personal and societal benefits. Hopefully, future research can imagine how the benefits of hypermobility and globalised practices can be maintained with lower environmental footprints and altered mobilities.

Ongoing debates on flyer’s shame – in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic – indicate that consumers are increasingly aware of the environmental footprint of air-travel. The question is how social practices tied to work, leisure, and extraordinary events can be shifted to accommodate this concern. Both material interventions in mobility infrastructures and broader socio-cultural changes in values and expectations can affect the normative performance of practices.

The thesis might also inform inquiries into how the Covid-19 pandemic can be a window of opportunity for transitioning towards sustainable mobility. Submitted only months before the pandemic shook global aviation, the thesis presents a timely contribution to the Mobilities scholarship on the social and environmental implications of global consumer mobility, which is now being re-imagined as the aviation landscape is changing.

It becomes clearer than ever that when our broader practices change, our mobilities change with them. Future research will have to address pitfalls and opportunities for more sustainable consumer (aero)mobility as societies normalise in the ‘post-pandemic’ world.

Johannes Volden & Arve Hansen (2022), Practical aeromobilities:making sense of environmentalist air-travel, Mobilities, 17:3, 349-365, DOI: 10.1080/17450101.2021.1985381Practical aeromobilities: making sense of environmentalist air-travel

1 https://www.toi.no/getfile.php?mmfileid=48774

2 John Urry, The ‘System’ of Automobility, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 21, no 4-5, 2004 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0263276404046059

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xPolicies

To cite this publication :

Johannes Volden (25 October 2021), « Flying Through a Perfect Moral Storm: How do Norwegian environmentalists negotiate their aeromobility practices? », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 10 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/new-voices/13819/flying-through-perfect-moral-storm-how-do-norwegian-environmentalists-negotiate-their-aeromobility