02 February 2022

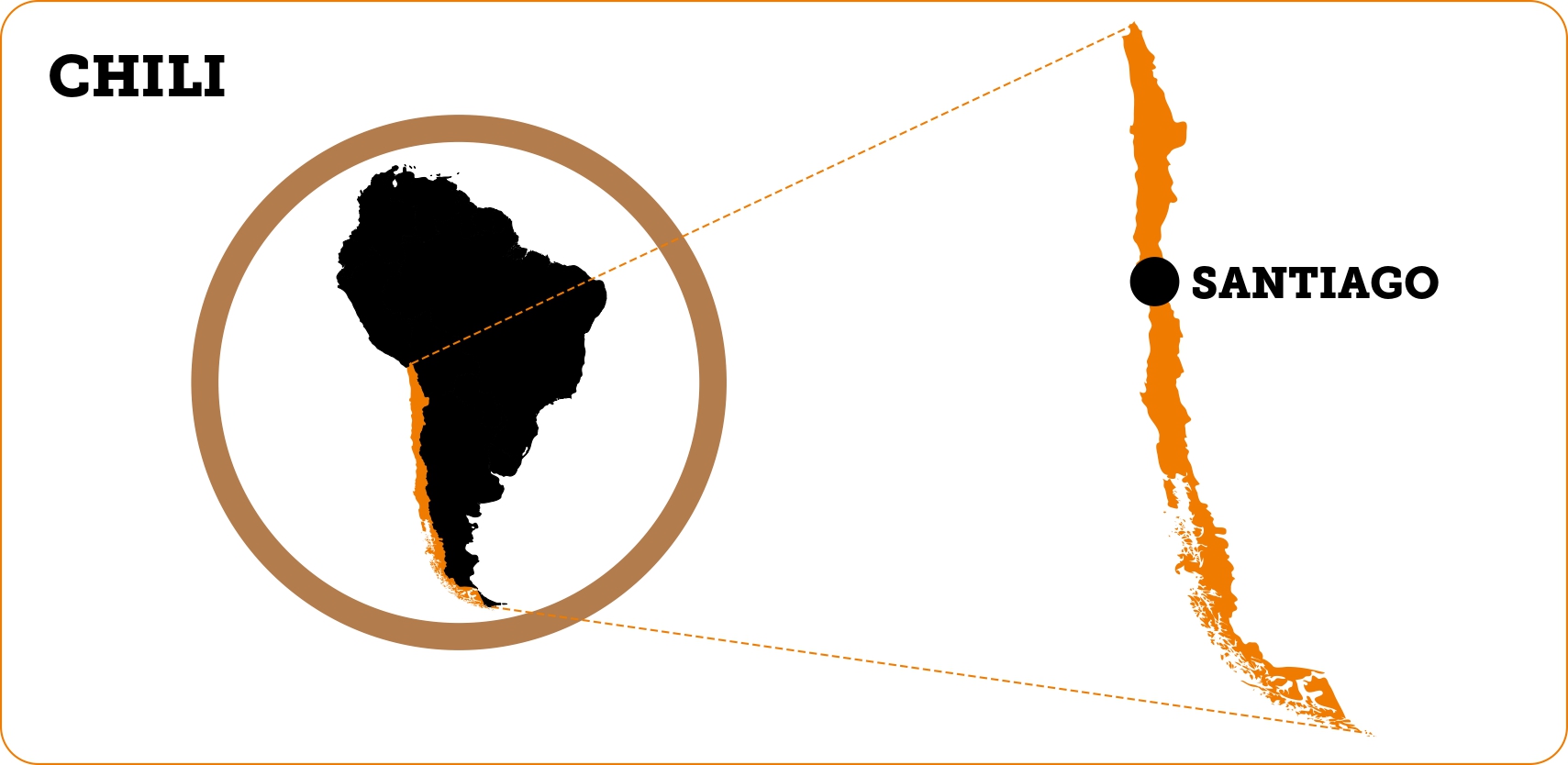

Cycling movements have multiplied in South America, particularly in Santiago de Chile, where their scope has brought together all kinds of demands: social, feminist and ecological. Matthieu Gillot and Patrick Rérat followed this "plurinational cycling revolution" which brings together several thousand people every week.

In Santiago de Chile, a city with 8 million inhabitants, a social crisis erupted in October 2019, prompted by an increase in the price of metro tickets. Students began a fare dodging campaign with the slogan "Evadir, no pagar, otra forma de luchar" ("Evade, don't pay, a different way to fight!"). The ensuing protests more generally called into question several decades of neo-liberal policies and the privatisation of institutions such as education, health or pensions. Cycling collectives joined this protest, calling themselves the "Plurinational Cycling Revolution." Their first rally attracted 35,000 people on October 27, 2019. Since then, except during a period of lockdown, several thousand cyclists have gathered every Sunday (for a total of 88 gatherings at the beginning of December 2021), converging on the city centre.

Figure 1: Cycling Revolution no. 29 of November 15, 2020 in front of the Presidential Palace (source: Cristián Cuevas Barazarte)

A mobilisation can be defined as “the action by which individuals are called to mobilise and gather in the public space in order to achieve a concerted goal" (Landriève et al. 2017). 1 The most well-known cycling mobilisations on an international scale are the Critical Masses (Furness 2010) during which cyclists travelled in large numbers with the slogan "We don’t block the traffic, we are the traffic" (White 1999). Born in San Francisco in 1992, this movement has spread throughout the world. In Santiago, the Movimiento furiosos ciclistas ("Furious Cyclist Movement") launched the "Cicletada de primer martes” in 1995, based on this model.

The Plurinational Cycling Revolution takes the principles of the Critical Masses, but distinguishes itself through demands that go beyond the realm of cycling and into different political arenas. Our premise is that this convergence of demands is an emblematic expression of the concept of mobility justice, developed by sociologist Mimi Sheller.

For Mimi Sheller, 2 the right to mobility is a freedom that must be won. Many restrictions in this area generate significant disparities and inequalities and, without mobility, there are no relational processes. The notion of mobility justice allows us to think of a triple crisis operating at several scales (from the body to the street, the city, the nation, and to the whole planet) and that refers to different forms of mobility. More specifically, these are: (1) the urban crisis (inequalities in access to transport and amenities), (2) the environmental or climate crisis (CO2 emissions, etc.) and (3) the migration crisis (population movements to escape, among other things, the effects of climate change). This notion should allow us to build bridges between different approaches and debates about the different spatial mobilities and to bring them together into an overarching discussion on how to rethink lifestyles and the transition to low-carbon mobility.

We analysed the Plurinational Cycling Revolution of Santiago from October 2019 (beginning of the social crisis) to October 2020 (referendum on the constitution proposed by the government). In the first months, through participant observation during demonstrations and meetings, as well as through interviews (with the RPC’s spokesperson on social networks, the director of a pro-cycling organization, an activist member of several cycling NGOs and a feminist cycling activist), we were able to collect information on the various messages and slogans. During the pandemic, we followed the mobilisations via social networks. We compiled and analysed an inventory of the materials used (flyers, slogans, etc.) by visual methods (Rose 2016). This article gives an overview of the main cycling, political, environmental and feminist demands.

Just like the Critical Masses, a first series of demands concerned the place of cyclists and their right to the city. The Plurinational Cycling Revolution appeared in a context where cycling is growing, particularly in connection with the social crisis and the metro’s shutdown. Bikes are an alternative to the automobile in a congested city where cars remain a symbol of social success. The cyclists’ demands are directed at the scale of their bodies (safety, integrity) but also at the scale of the city of Santiago (accessibility), referring to the need for adequate infrastructure for utility cycling (beyond "recreational bike paths") and its legitimacy as a means of transport. The health crisis favours the practice of cycling because of the need to respect social distancing. This is reflected in some slogans like "More bike lanes, less contagion." However, informal workers (1/3 of the working population) living on the outskirts can’t access the new cycle paths and have to contend in particular with a lack of secure parking near public transport stations (Jirón 2020). During this period, cycling collectives organised repair workshops, brought essential goods and organised "ollas comunes" (soup kitchens) in poor neighbourhoods.

In September 2020, during the lockdown, numerous fatal accidents involving cyclists were caused by speeding motorists and bus drivers in a less-congested city. After a break from March to September 2020, cyclists took to the streets again with the slogan “No + cyclistas muertxs” ("No more dead cyclists") (Figure 2). The movement's demands, however, went beyond cycling activism, as shown by the other two slogans of the flyer: "I approve"(Apruebo; in reference to the referendum on the Constitution) and "Dignity, the planet, your future."

Figure 2: Flyer of the Cycling Revolution of October 11, 2020

The initial slogan of high school students ("Evade, don't pay, a different way to fight!") was adapted by the cycling collectives into: Evade, pedal, a different way to fight! During their rallies, cyclist collectives also voiced the political demands of demonstrations taking place throughout Chile: demands for a new Constitution, calls for the resignation of government officials, and in general, a rejection of the privatisation of essential institutions (education, health, pensions). The Mapuche flag, representing the country's indigenous population that isn’t recognised in the Constitution, was present during demonstrations (Figure 3). The term "plurinational," which was already included in the new Bolivian Constitution of 2009 backed by Evo Morales (the country’s first Indian president), was added to the movement’s name during its 4th event to recognise the country’s multiculturality. The routes of the cycling revolutions connected the symbolic places of power (the presidential palace) and of protest (the starting point being Plaza Italia, located between poor and rich neighbourhoods, and renamed Dignity Square).

Figure 3: Mapuche flag during the Cycling Revolution of February 28, 2021 (source: Alfonso Atavales Gallardo)

Environmental claims (Figure 4) referred to several levels of action, as shown by the slogan "Our dignity, our planet, your future". According to the director of a pro-cycling organisation, "cycling in Santiago has stopped being merely a form of transport to become the expression of an eco-friendly awareness [...] and the climate crisis represents a unique opportunity to achieve this transformation." The environmental claims are directed both at the global level (climate change, finite resources, recycling, etc.) and the city-level, considering that Santiago is among the most polluted cities in the world, with significant sections of the population suffering from pollution. The cycling movement supports the right to live in a healthy environment and advocates for environmental justice. Some gatherings specifically pursued such goals, like Biciforestation (reforestation by bike) or the promotion of the Mapocho Ciclo Parque, a bike path through Santiago along the Mapocho River.

Figure 4: Cycling Revolution Flyer for World Recycling Day on March 18, 2020

The Cycling Revolution is also a platform for a number of feminist demands to express themselves in what remains a largely patriarchal culture. Many protesters wear a green headscarf, a symbol of Latin American feminist movements created in 2003 by Argentine feminists in their fight for abortion rights. There are large-scale rallies such as the "Women's Plurinational Cycling Revolution" that gather thousands of people, mainly on March 8 (International Women's Day) and November 25 (International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women). Other smaller events such as the "Girls' Bike Ride" bring together tens or hundreds of participants at monthly events. Created in Chile, this mobilisation is now active in several other countries such as Peru, Ecuador and Mexico.

Figure 5: Girls' Bike Ride, March 7, 2020

The "Girls' Bike Ride" flyer (Figure 5) expresses both a call for greater cycling safety within the city (including with children) and more specific demands with the feminist logo and the LGBT+ rainbow flag. During these cycling events, participants feel safer and less vulnerable (with regards to men and cars) thanks to a group effect (or "mass" effect, to use the name of traditional cycling mobilisations). Finally, other arguments focus on the potential benefits of becoming a regular cyclist: increased confidence in oneself and in one's physical and cognitive abilities, greater autonomy in one's movements, participating in social and economic life through access to more job opportunities and other places of daily life and, ultimately, enjoying a sense of belonging to a city (Mundler et Rérat 2018). These demands are expressed at the level of the body and the street (integrity) and at the level of the city (accessibility).

The Plurinational Cycling Revolution of Santiago takes up the principles of the Critical Masses. It brings together cyclists who travel the city in large numbers and who call for cycling to be better recognised (through infrastructure and reconsidering the place of car traffic). However, it differs from traditional cycling mobilisations by also serving as a platform for political, environmental and feminist demands. It is therefore part of the wider protest movements that have been occurring in Chile since October 2019.

By using the lens of mobility justice (Sheller 2018), the analysis shows that these claims refer to mobility crises. They highlight inequalities in people’s ability to travel safely according to social class, gender, sexual orientation or mode of transport, and criticise the structures that perpetuate them (political system, neoliberal economy, patriarchy, automobile system). They also illustrate how mobility crises occur at different scales: the body (relying on physical strength to get around, safety and integrity concerns), the city (access to urban amenities), the country (political system), and the whole planet (environmental impacts).

While our study didn’t focus on its effects, the RCP did strengthen the visibility and legitimacy of cycling in Santiago and its different neighbourhoods. It also attracted people who did not belong to the cycling collectives but who took part in the general protests. In conjunction with the Sunday demonstrations, measures have been taken to ensure the safety and protection of cyclists (such as amending the road safety rules regarding sanctions for drivers involved in collisions with cyclists). Some temporary cycle paths proposed by the RPC during the pandemic have also become permanent.

Cycling appears to be a resilient (Héran 2020) mode of transport in the political, economic, social and health crises experienced by Chile and its capital. As a focal point for multiple demands, it is also used as a symbol of "transformation" (Salazar 2019) and as a vector of a struggle for systemic change in Chilean society.

This article is from the project "Collective cycling mobilisations in South America: Right to the city and mobility justice" (CRSK-1_190831) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Furness, Zack. 2010. One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility. Temple University Press.

Héran, Frédéric. 2020. "Le Vélo, Ce Mode de Déplacement Super Résilient” [Cycling, This Super Resilient Mode of Travel] The Conversation. May 11, 2020. http://theconversation.com/le-velo-ce-mode-de-deplacement-super-resilient-138039

Jirón, Paola. 2020. “Desafíos de la ciudad post pandemia” [Challenges of the post-pandemic city]. Núcleo Milenio Movilidades y Territorios (blog). May 29, 2020. https://www.movyt.cl/index.php/prensa/noticias-movyt/portada/foro-desafios-de-la-ciudad-post-pandemia/ . https://www.movyt.cl/index.php/prensa/noticias-movyt/portada/foro-desafios-de-la-ciudad-post-pandemia/

Landriève, Sylvie, Villeneuve Dominic, Kaufmann Vincent and Christophe Gay (2017), "Mobilization", Mobile Lives Forum. Accessed May 12, 2021, URL: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/marks/mobilization-3612

Mundler, Marie, and Patrick Rérat. 2018. "Le vélo comme outil d’empowerment. Les impacts des cours de vélo pour adultes sur les pratiques socio-spatiales” [Cycling as an empowerment tool. The impacts of adult cycling lessons on socio-spatial practices.] Cahiers scientifiques du transport, No. 73: 139‑60.

Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials.

Salazar, Myriam. 2019. “Tiempos de transformación” [Times of transformation], Revista Pedalea (blog). December 5, 2019. https://revistapedalea.com/tiempos-de-transformacion/

Sheller, Mimi. 2018. Mobility justice: the politics of movement in the age of extremes. London; Brooklyn, NY: Back.

Sheller, Mimi (2019), "From the street to the planet: can mobility justice unite our diverse struggles?“, Mobile Lives Forum. Accessed May 12, 2021, URL: https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/video/2019/11/26/street-planet-can-mobility-justice-unite-our-diverse-struggles-13111

White, Ted. 1999. WE ARE TRAFFIC!: A Movie About Critical Mass. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lpsdy24xbLY.

1 While our topic is cycling mobilisations (see also Manga Tinoco; https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/project/2021/08/25/role-bike-movements-ecological-transitions-13746), other movements were also motivated by mobility issues, such as the "smile revolution" in Algeria ( https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/2019/07/01/spatial-underpinnings-revolutionary-protests-algiers-12997) or the yellow vests in France ( https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/project/2020/07/03/yellow-vests-and-mobility-crisis-what-did-true-and-great-debates-lead-13388).

The lockdown measures implemented throughout 2020 in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, while varying from one country to the next, implied a major restriction on people’s freedom of movement for a given period. Presented as a solution to the spread of the virus, the lockdown impacted local, interregional and international travel. By transforming the spatial and temporal dimensions of people’s lifestyles, the lockdown accelerated a whole series of pre-existing trends, such as the rise of teleworking and teleshopping and the increase in walking and cycling, while also interrupting of long-distance mobility. The ambivalent experiences of the lockdown pave the way for a possible transformation of lifestyles in the future.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xFor the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMobilization is the action by which individuals are called upon to gather in the public space for a concerted effort, be it to express or defend a common cause or to participate in an event. In this respect, it is a social phenomenon appertaining to mobility. This article has been written by Sylvie Landriève, Dominic Villeneuve, Vincent Kaufmann and Christophe Gay.

En savoir plus x

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications