21 February 2022

With more than 10 million inhabitants, Ho Chi Minh City is not only the economic powerhouse of Vietnam; it is also the world’s capital of scooters and other motorized two-wheelers (“motorbikes” for short). Less than ten years ago, in 2014, nearly all households (83%) owned at least one motorbike according to a large survey conducted by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Today, riding a motorbike remains the most convenient way of traveling the narrow roads and alleyways that cut through this particularly dense city. While a rising number of cars is making motorbike mobility increasingly uncomfortable, difficult, and dangerous, motorbikes might soon become a memory of the past.

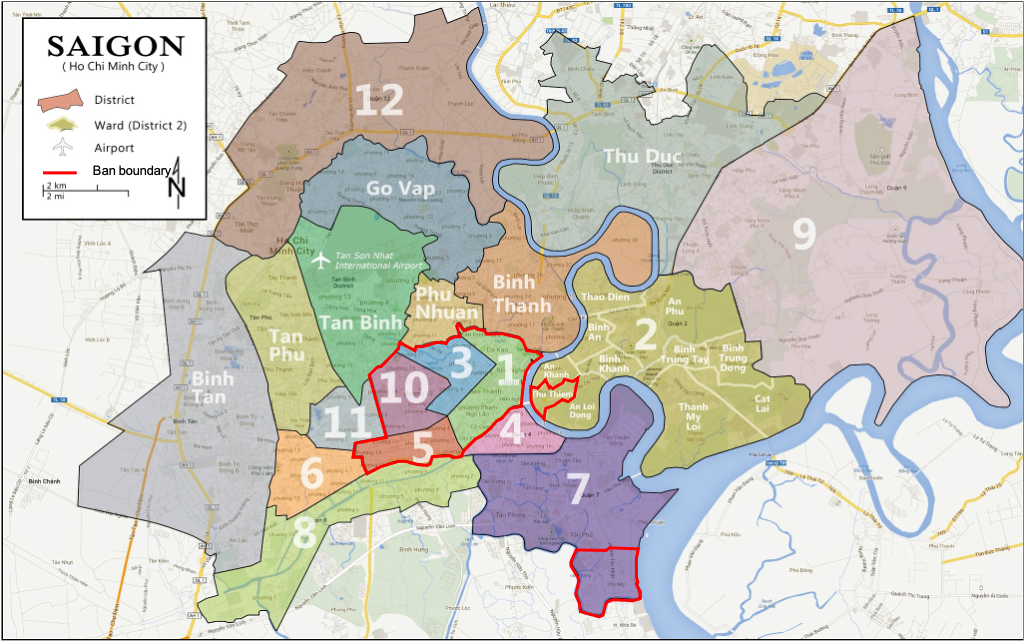

There is a ban on motorbikes on the horizon. If all goes according to plan, in less than ten years from now, by 2030, motorbikes will be denied access to four central districts (1, 3, 5, and 10) and two new urban areas of Ho Chi Minh City. What are the motivations of the decision-makers? And how do residents feel about it?

Figure 1 – Motorbike-restricted areas by 2025 (created by the author, based on map by Codie Leseman available here: https://codiemaps.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/saigon-map.jpg)

My name is Huê-Tâm Jamme. I am an Assistant Professor at the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at the Arizona State University. I worked for several years in Vietnam between 2007 and 2015. To answer these questions, I returned to Ho Chi Minh City for five months of fieldwork in 2018. I recorded more than 300 videos of traffic flows and street life and I spoke with decision-makers, transportation specialists, and 32 residents.

I cannot foresee whether the government will back up or hold strong, fail or succeed, in implementing the highly disruptive plan they have adopted. In this regard, I will simply echo one of my respondents – a wise elderly Vietnamese man speaking about his compatriots:

“Vietnamese people have surprised me before. I thought they would never accept to wear a helmet; the helmet law was enforced overnight. I thought they would never want to live in apartment buildings; they love it.”

What I can do, however, is report on the reactions of those who would be most directly impacted by this plan: the people who inhabit the city. Their voice is typically missing from mobility research in the Global South.

Note that this article is a summary of a research paper published in summer 2020 in EchoGeo, in a special issue edited by Marie Gibert-Flûtre and Clément Musil. 1

This is Ho Chi Minh today: busy streets and sidewalks crowded with motorbikes at any time of the day. According to my estimates, if one were to walk for half-a-mile on the sidewalk of an average commercial street in Ho Chi Minh City, they would zigzag among 247 parked motorbikes – and also 129 people hanging out in public space, not walking, but eating, drinking, chatting, socializing.

Figure 2 – A typical boulevard of Ho Chi Minh City (photo credit: author, 2018)

And “this is not what the modern city looks like,” according to a transportation planning professor who regularly consults for the local government. For him, the “modern city” is Singapore, Seoul, Moscow, Tokyo – cities he visited to learn from their “best practices,” where motorbike mobility is virtually non-existent and street life much more regulated.

Against the backdrop of rapid urbanization, Ho Chi Minh City is being modeled by its leaders on other Asian cities, Singapore in particular, considered more advanced economically, more “modern” in terms of esthetics and infrastructure, and better integrated into the global economy. As such, Ho Chi Minh City is the prototype of a “worlding city,” a term coined by urban scholars Ananya Roy and Aihwa Ong. 2 I argue that urban transportation policies, including the ban on motorbikes, qualify as “worlding practices,” that is, urban interventions that attempt to establish new standards inspired by cities that are economically more advanced but culturally not as foreign as Western Europe or North America.

Figure 3 – Motorbikes in the interstices of urban life (photo credit: author, 2018)

In official discourses, the ban on motorbikes is a policy response to issues of congestion, pollution, and traffic-related fatalities, which have grown exponentially along with the demand for private motorized mobility since the economic reforms of the early 1990s. The skyrocketing number of cars since the mid-2010s has further aggravated these issues, which take a toll on economic growth (congestion alone is considered to be responsible for a 2-3% GDP reduction). In 2014, cars represented 1% of all trips in Ho Chi Minh City, according to the JICA survey. My traffic counts showed that cars accounted for 10% of all moving entities on the streets I surveyed in 2018, and they occupied more than 20% of the road space in certain areas.

First raised by the Prime Minister in 2013, the idea of banning motorbikes coincided with the lessening of restrictions on cars. Until then, severe import taxes on foreign cars aimed to limit access to car ownership precisely because of the lack of infrastructure to support car mobility. But nowadays, a “car-dependent transport system” is under development in Vietnam. Four constituents of such a system, as defined by Giulio Mattioli and his co-authors, 3 have emerged:

Mass transit is presented as the ultimate alternative to motorbike mobility in the future. Nevertheless, only one line is currently under construction. After years of delays, it is due to open at the end of this year (further delays notwithstanding) but it is expected to meet only 2-3% of the demand for urban mobility by 2025.

Surprisingly, most of the residents I interviewed were supportive of the ban on motorbikes, including those whose mobility entirely depends on the ability to ride one.

One of them is Minh, 5 for example, a 52-year-old key repairer who claimed, among other reasons for “liking” his current travel mode: “My motorbike is my freedom.” Minh lives in a central district targeted by the ban. He works more than 20 km (12 miles) away, in Binh Chanh District, which will not be connected by rail transit anytime soon. He makes a meager VND 6 million per month (USD 260). Neither the car nor the metro can possibly become a viable mode of transport for him in the near future. Of course, he worries about the consequences of a ban on motorbikes – “What are we going to do?” he asks, rhetorically – however, he is not against it.

Figure 4 – A busy street at peak hour between jammed cars, buses, trucks, and motorbikes (photo credit: author, 2018)

Generally supportive, reactions to the ban can be classified into three categories depending on people’s adaptability.

First, there are The Resigned, who seem willing to make the necessary sacrifices – “It’s gonna be very hard to live without motorbikes. But we have to do it” said a middle-class educated 32-year-old woman. The Resigned trust their resilience.

Second, there are The Resolute who demand the ban. They feel prepared. They have the necessary cultural and financial capital to adapt, as exemplified by this other young female white-collar worker who said:

“First thing I do once they ban motorbikes: I buy a car.”

Third, there are the Fatalists, like Minh, or this 35-year-old waiter who foresees that: “It will happen. I don’t know when, but it will happen.” The Fatalists are unsure about how to cope with the ban. They can only hope that hardships related to implementation will buy them some time.

To explain the surprising reactions of support to the ban, I advanced the proactive role of “worlding individuals” eager to take part in the implementation of “worlding practices.” The reasons for supporting the ban are not practical but symbolic. Those who have purchased a car enjoy the comfort and safety it provides but they admit that it is not convenient in Ho Chi Minh City today. They complain that “it is very slow;” “there is nowhere to park;” “we get stuck in traffic.” Most respondents cannot really picture how they will integrate transit into their habits.

Nevertheless, people aspire to these new forms of mobility for what they represent: a modern lifestyle in a modernized urban environment. About mass transit, one respondent sees it as “a sign of modernity;” another observed that “all developed countries have it; we have to imitate.” As for the representations attached to shifting away from motorbikes, one participant argued that “restricting the number of cars rather than that of motorbikes would be going backward. Banning motorbikes, that is going forward.”

In sum, it seems like most people would rather make the necessary sacrifices induced by a ban on motorbikes than be left behind in the race towards progress, development, and modernity.

Only one of the participants reacted strongly against the ban on motorbikes. Her name is Phương. She sees in this policy a serious problem of social inequalities:

“The poor, they can’t afford to buy a car! So, they depend on their motorbike. The rich, they will be able to use their car. But when are we gonna have a car? Who doesn’t dream to have a car? But we can’t afford it! We’ll have to take the bus. I have nothing against the bus, nothing against the metro either, but we won’t be able to go wherever we want like we do now. […] I really think this idea is unacceptable. […] I’m totally against it.”

Phương expresses the injustice felt by those left behind. She raises the important question of the socioeconomic tensions that ensue.

Figure 5 – Back from school on the back of a motorbike (photo credit: author, 2018)

The process indeed works to the advantage of the upper-middle classes, and at the expense of the quality of life of the others. Each car that is added to the traffic of Ho Chi Minh City impedes a little more the mobility of the majority, that is motorbike riders. The increased comfort and safety enjoyed by a minority of car users comes at the expense of the road safety of the majority. Ngọc, a wealthy entrepreneur who only travels by car (with a driver), is aware of this inequality. As she puts it: “In an accident involving a car and a motorbike, most of the time someone dies; and it rarely is the person in the car."

Furthermore, the car will remain unaffordable for the majority for many years. As for the metro, designed like the Bangkok SkyTrain as a commuter rail system rather than a means of intra-urban travel, it will primarily serve the middle and upper classes who work in the center but live in the “suburbs.” Such a way of life, which can be qualified as “modernized”, with clear demarcations between places and times dedicated to work, rest, and leisure, contrasts with the existing urbanism of Ho Chi Minh City, characterized by its blurred boundaries – spatial and temporal – between the different uses of the city. 6

The work featured in this article explored the politics of a “mobility transition” that goes in the opposite direction to those typically studied by mobilities scholars: not away from but towards automobile dependence. In Ho Chi Minh City, the priority given to cars over motorbikes is highly political. It stems from broader trends of structural change and it has far-reaching consequences for social and spatial justice.

Although people seem in favor of shifting away from the motorbike, it remains the government's responsibility to limit the sacrifices involved. The plan to ban motorbikes will hit the most disadvantaged especially hard. Public transportation remains the most equitable path towards the modernization of mobility. However, modern mobility is not limited to the car and the metro. Modern mobility needs to be reinvented, planned, coded, and implemented.

Electrifying, rather than removing the motorbike fleet should be considered. Not as popular in Vietnam, electric two-wheelers have been described as quite a successful innovation in China, (albeit disruptive for the emerging system of automobility). 7 Walking and biking, still stigmatized as the modes of the poor, and of the past, could be brought back to the fore as the modes of the future. Biking, for example, has remained a popular mode for recreational purposes, especially among men of all socioeconomic backgrounds. 8 Why not build on this popularity to promote it as a healthier, more sustainable way of getting around? Instead, biking remains nearly absent from Ho Chi Minh City’s transportation plans.

These existing mobilities, coupled with new mobilities – micro-, on-demand, shared mobilities, and the like – could be integrated into transportation planning and policies. Like other motorbike cities of the Global South, Ho Chi Minh may even be in a position to take the lead in the race towards modern mobility, where modernity would mean contextually appropriate, multimodal, just, and sustainable mobility; and not "auto-mobility".

1 For the full-length article, see: Jamme, Huê-Tâm. "Transition mobilitaire et disparition des motos à Ho Chi Minh Ville: le rôle de l’individu dans la réalisation de pratiques globalisantes." EchoGéo 52 (2020). https://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/19647

2 Roy, A., & Ong, A. (2011). Worlding cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global. John Wiley & Sons.

3 Mattioli, G., Roberts, C., Steinberger, J. K., & Brown, A. (2020). The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach. In Energy Research and Social Science (Vol. 66, p. 101486). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486

4 See Hansen, A. (2016). Driving development? The problems and promises of the car in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 46(4), 551-569 and https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/mobilithese/2018/09/17/hanoi-metamorphosis-bicycles-motorbikes-12657

5 Pseudonyms are used throughout this article

6 Sidewalks and narrow residential alleyways have often been described as the extension of people’s private quarters, their homes and businesses. Alternatively at different times of the day, or simultaneously, the same space can be used for motorbike parking, displaying merchandise, washing dishes, setting up tables and chairs, eating, drinking, playing, etc., or just hanging out.

7 See https://en.forumviesmobiles.org/video/2014/10/07/china-time-green-revolution-2580

8 A very recent article suggests that this popularity has grown after the onset of the pandemic. See Nguyen, M. H., & Pojani, D. (2022). The emergence of recreational cycling in Hanoi during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Transport & Health, 24, 101332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101332

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xLifestyles

Policies

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.