New voices 30 May 2022

Residential choice has been well analyzed. But less is known about the role played by private real estate professionals – who are the main contact for households looking to buy property – and even less about their consideration of Housing and Transportation Cost, i.e. the expenses in terms of housing and daily mobility borne by households once in their new home. Maria Besselièvre approached this subject by meeting households and professionals from Grésivaudan, an attractive valley linking Grenoble and Chambéry. This work received the 2021 New Voices Award from the Mobile Lives Forum.

New Voices Awards 2021

Thesis title: Prise en compte du coût résidentiel par les professionnels privés impliqués dans les recherches immobilières des ménages. Exemple d’une vallée attractive : le Grésivaudan (38)

Country: France

University : ENTPE, École de l’aménagement durable des territoires

Date: 2019

Research supervisor: Jean-Pierre Nicolas

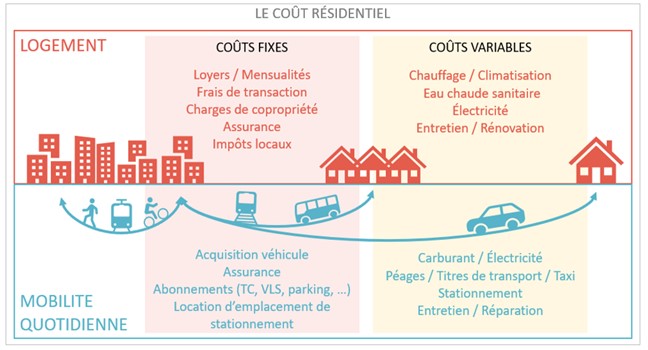

Maria Besselièvre – This work focuses on household Housing and Transportation Cost. To explain this notion, we need to outline the context. Since the beginning of the century, rising energy and housing prices, as well as increasing levels of fuel poverty, have called into question lifestyles which rely on long commutes. According to Anne Dujin and Bruno Maresca, these situations are a symptom of growing social and territorial inequalities that are reflected in the residential situation of households. The residence, spatially located, directly affects daily expenses of the household: living in a certain place involves paying rent or a mortgage, energy bills and taxes, but also daily mobility expenses to go to work, do shopping or access services. Yet, depending on the city, the supply of housing and public transport, taxation, public assistance, etc. varies. To address these inequalities, these researchers introduce a new and cross-disciplinary concept: Housing and Transportation Cost. It can be defined as all expenses incurred due to a particular choice of residence. More concretely, it consists in “adding up the cost of housing, including utilities, and the cost of mobility according to the type of town or city of residence." (Maresca et Dujin 2013:1) The key idea of this concept is that it is not a single item of expenditure that puts a strain on households, but the accumulation of multiple financial demands and necessary expenses. Treating items of expenditure separately therefore runs the risk of rendering invisible many vulnerable households, or those that are even already in a precarious situation.

Figure1: Schematic representation of Housing and Transportation Cost. Produced by Maria Besselièvre.

In my work, I focused on choosing a place to live. This can be defined as evaluating a property on the housing market and involving a trade-off between aspired quality of life, accessible resources and a territorial context. Housing choice plays an important role in determining different factors in the Housing and Transportation Cost of households and redefining routines (Meissonnier 2015; Vincent 2010). Some studies have pointed out that the costs of mobility are often underestimated (Maresca et Mercurio 2014). Choosing a property can be seen as a project involving third parties, including private professionals. Their place in this process has rarely been studied, even though they are at once advisors to households, privileged partners of public actors and profit-seeking economic actors. (Bonneval 2014) They can act both as a resource and a filter and are often at the forefront in terms of tools for calculating Housing and Transportation Costs. (Cauhopé et Grangeon 2018) One question emerged from these observations: to what extent do these private professionals assess - completely or partially - the Housing and Transportation Cost of a household looking for a property?

Maria Besselièvre – My study was limited to the Grésivaudan valley (Isère department), a mountainous peri-urban area under strong land pressure, and under the influence of both the Grenoble metropolis and the Chambéry agglomeration. I took a qualitative approach, performing semi-structured interviews (almost unstructured) with:

Maria Besselièvre – A review of the literature shows the limits of isolating individual approaches when addressing three contemporary issues related to residential choice: urban sprawl, energy poverty, and climate change. These limits call for more trans-disciplinarity, particularly in the affordability indicators, used to describe a household’s ability to acquire / rent a property with regards to its availability, its cost (direct and/or associated), and its suitability for the household (Lipman 2006; Mattingly et Morrissey 2014). The notion of Housing and Transportation Cost can cover different interacting temporalities and dimensions – objective and subjective, individual and structural – which is an essential condition for comparing residential choice and resulting lifestyle (Thomas 2014). The transdisciplinary and multidimensional nature of Housing and Transportation Cost (as defined in this way) requires, for its operational aspect, the coordination of public and private actors, from in different sectors (housing, land, mobility, energy, banking, social action, etc.) and working at distinct scales, both spatial (municipality, intercity, department, etc.) and temporal (short-term, mandate period, long-term, etc.).

When looking for the reasons why inhabitants want to live in Grésivaudan, we find that their decision-making process occurs at the crossroads of a macrostructure made up of social, economic and historical dynamics, and a microstructure that differentiates each property by how it represents the territory and its ideal way of life. This complex structure must be applied in a territorial context which does not offer solutions where both the housing and associated mobility are adapted, affordable, healthy and sustainable. Residential choice appears to be based not on a cost-benefit calculation, but on compromises involving adjustment variables (moving away, renovating, building or self-building, or even giving up on residential mobility). This leads to difficult situations for households that did not anticipate certain associated costs incurred as a result of moving — for example, costs related having to travel longer distances or more frequently for work.

Anna, one example among others

After having lived in Reunion, Anna was transferred to Pontcharra. Her husband, who works in construction, found a job in Grenoble. They wanted to settle down between the two locations with their three children. Seeing the high rental prices in Grésivaudan, they decided to buy in order to build up capital. However, properties were expensive and her husband noticed that a lot of renovation work was required at each one...

“I don't really like agencies, I can’t explain it. Every time we went through them, it was bad. We visited some places, and given the price, there was too much work to do. [...] My husband works in this field, so we spot all the issues. There are things... a lot of people would be fooled! Often people do the renovations themselves and don’t know how to do it properly, and they tell you: "[...] You can just move straight in!" [...] First there is the price, plus the notary fees which for old properties are much higher, and then there is cost of renovating everything. So in fact, for us, it was much cheaper to do it ourselves.”

After finding a plot of land in Villard-Bonnot, they decided to build. However, hiring a builder was again too expensive. So they did it themselves. Although they would have preferred it, they were unable to use healthy and environmentally friendly materials - too expensive. At first, her husband commuted by train to Grenoble, but he was asked to travel with a company truck. "This made his schedule crazy!" So, he started his own business and had to invest in a van. Running a business, a large family and building the house was not viable for very long. "That’s it, no more." Anna's husband decided to devote himself entirely to the construction of their house. Nevertheless, with one salary, the budget was tight.

“In August, we have to be in it. So we have to speed things up. Because with the rent, plus the mortgage, it’s going to sting. So we have to move in, we have no choice.”

This is Anna's situation, but I could have told you about Sophie, a nursing assistant at the hospital who left Pontcharra to buy in Drumettaz after her husband was transferred to a bank in Annecy. Spending 20 € per day for tolls and petrol was no longer feasible! Because they are not very good at manual labor, they managed to find a house in good condition. "A stroke of luck!" But now she cannot go to work by train and has to drive the car too.

There is also Malika who accompanies her neighbor to the Secours Populaire, a non-profit organization fighting poverty. Even though she has a car, her neighbor cannot afford to put gas in it. She would like to move, as she is tired of having to use several means of transport to get to work nearly 40 km away. But moving is expensive. .

Not to mention François and his wife, both doctors, who bought a house in “pretty good condition” further away than expected. Afterwards, they came to realize how the distance was a burden when on-call, and the extent of the renovations needed. Because it was too expensive to hire professionals, they did it themselves but ended up regretting it as they did not fully insulate it.

We could also have mentioned Leon and Marion, and all the other people we did not meet.

It seems wise therefore for experts to help households in choosing a property and assessing Housing and Transportation Cost. Yet no actor involved in the process of choosing and buying a property really considers these factors, even those taking an economic risk such as the banker. While real estate agents could be be relevant actors here, despite their economic interests, they mainly hold a paradoxical position between advisor and salesperson, and must comply with the standardized process of the real estate transaction. The factors taken into account depend above all on the regulations that govern real estate sales. Mobility often seems to be relegated to the bottom of the list while the energy cost of housing is increasingly looked at since the implementation of the Energy Performance Diagnosis (commonly called DPE in France).

The study of the changes in how professions consider Housing and Transportation Costs is mixed. Some actors, especially optional ones (for example real estate agents), diversify their areas of expertise, while others, often the unavoidable ones (for example bankers) tend to specialize. As a result, optional actors seem more likely to have a systemic view of the real estate transaction. It would be easier for them to quickly integrate the notion of Housing and Transportation Cost into their approaches, in particular via continuing education. Secondly, the growing importance of IT has the effect of physically distancing professionals from their customers while intensifying the flow of information. The information is more accessible, but not necessarily relevant or required. Properties are more visible, but also sorted according to particular criteria. The Internet may support tools to facilitate rentals or calculate Housing and Transportation Costs, but this doesn’t guarantee that these tools are known about, perceived as being useful or used. Finally, the study of how relations between actors have evolved has shown that beyond the development of devices that increase the understanding and interconnection between intermediaries and clients, it seems possible and relevant to establish links between the world of real estate and the world of mobility.

Recent work on the development of tools for calculating Housing and Transportation Cost is worth pursuing (Cauhopé et Grangeon 2018). It would also be useful to strengthen the relationship between public authorities and private professionals and make it more transparent, by building a common understanding of the issues around shared data, agreeing on regulation and coordinating their actions.

Maria Besselièvre – Although the notion of Housing and Transportation Cost is not new (Maresca et Mercurio 2014; ONPE 2014), and the discussions related to it even less so, few works address it in these terms. However, in a context where the situation for lower income households is worsening, where commuting distances keep growing, and where the energy transition and climate emergency are major priorities, the apprehension of Housing and Transportation Costs reflects current social, territorial and environmental issues. Since the study was carried out, several crises have both renewed the importance of this subject and made it more complex. This work was done during the Yellow Vests movement. These protests expressed the desperation of the “little-middles” (in French, “petits-moyens”), people whose lifestyle, highly dependent on motorized vehicles, had become even less sustainable through repressive environmental policies (Cartier et al. 2008; Fourquet 2020). Their protests were interrupted in 2020 by the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns that enhanced social inequalities between precarious households, whose mobility is constrained and housing inadequate, and wealthy households, who have a greater freedom when choosing where to live, owing to their ability to perform teleactivities (Albouy et Legleye 2020; Forum Vies Mobiles 2020). Covid-19 remains active now but the Russian war in Ukraine is also raging, causing the price of energy and other everyday products to surge.

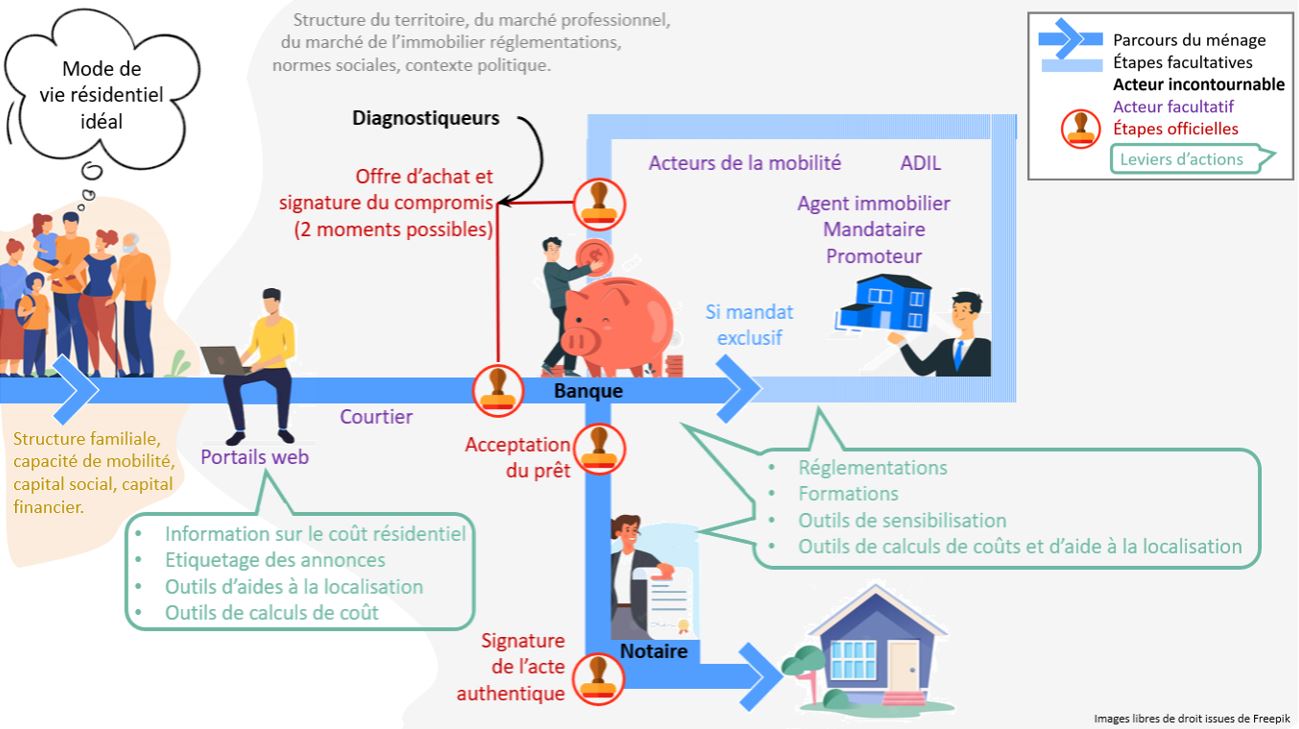

Far from covering this vast subject in its entirety, this thesis invites us to think about it beyond merely producing tools to help educate households, as recommended in the Clean Mobility Development Strategy (MEEM 2016, Développement de la Mobilité Propre). In it, residential choice appears as a complex decision that is not entirely free. It is a process in which public actors rarely intervene, which benefits private professionals who have their own interests and are yet poorly equipped to discuss Housing and Transportation Cost with households. Discussing levers of action to better integrate the assessment of Housing and Transportation Costs in the process of residential choice allows us to better consider how this key process can be the subject of public policies. This work has identified the first levers of action to integrate the assessment of Housing and Transportation Cost when planning to move house.

Figure2 : Housing access scheme, integrating levers of action to better integrate the assessment of residential cost. (Other actors could be added if necessary: Housing programs such as Action Logement, Social landlords, etc.). Produced by Maria Besselièvre.

Maria Besselièvre – The interviews for this thesis were carried out over a short period of time and were limited in number. In order to reinforce the findings, it would be interesting to broaden this approach, drawing on other territorial contexts. Furthermore, it was decided to survey only the professionals that the individuals studied had encountered. In order to highlight other levers of action, we could further explore the professionals who are rendered invisible by this methodology. I am thinking, for instance, of the Departmental Housing Information Agency (ADIL, Agence Départementale d'Information sur le Logement) or the Energy Info Spaces (Espaces Info Énergie).

This study focuses on the process of choosing a place to live. Nevertheless, the notion of Housing and Transportation Cost could be integrated into more structural discussions held by territorial actors: land use planning, building affordable housing, developing public transport, etc. For this, it seems necessary to know much more about household Housing and Transportation Cost and its determining factors at the territorial level. In this sense, the COUT-RES 1 research project offers a methodological quantification of household Housing and Transportation Cost in the regions of Grenoble and Clermont-Ferrand, via the implementation of a specific module within their respective household travel survey (EMC², for enquête ménage-déplacement). In this context and following this study, I am currently writing a doctoral thesis aimed at questioning the capacity of EMC² as both a technical and political instrument to support the transdisciplinary notion of Housing and Transportation Cost.

Finally, we have so far only talked about private Housing and Transportation Cost, i.e., borne by households. But a better knowledge of public Housing and Transportation Cost, i.e., borne by public authorities (costs of deploying networks and infrastructure, for example), would allow us to better understand the advantages or obstacles for public authorities to take up this issue.

Albouy, Valérie, et Stéphane Legleye. 2020. Conditions de vie pendant le confinement : des écarts selon le niveau de vie et la catégorie socioprofessionnelle. 197. INSEE.

Bonneval, Loïc. 2014. « Les tiers dans le choix du logement : comment les agents immobiliers contribuent à l’élaboration des projets résidentiels ». Espaces et sociétés n° 156-157(1), p. 145‑159.

Cartier, Marie, Isabelle Coutant, Olivier Masclet, et Yasmine Siblot. 2008. La France des « petits-moyens ». Enquêtes sur la banlieue pavillonnaire. Paris : La Découverte.

Cauhopé, Marion, et Damien Grangeon. 2018. Outils de sensibilisation à l’impact des choix résidentiels : état des lieux et perspectives. Note de synthèse. CEREMA.

Mobile Lives Forum. 2020. Survey on the impacts of the lockdown on French people’s mobility and lifestyles. L’Obosco pour Forum Vies Mobiles.

Fourquet, Jérôme. 2020. « La crise des Gilets jaunes : Somewhere contre Anywhere ». Constructif 1(55), p. 11‑14.

Lipman, Barbara. 2006. A Heavy Load: The Combined Housing and Transportation Burdens of Working Families. Washington DC: Center for Housing Policy.

Maresca, Bruno, et Anne Dujin. 2013. « La précarité énergétique pose la question du coût du logement en France ». Consommation et modes de vie (258):4.

Maresca, Bruno, et Gabriela Mercurio. 2014. Le coût résidentiel. Coût privé, coût public de l’étalement urbain. 321. CREDOC. Mattingly, K., et J. Morrissey. 2014. « Housing and Transport Expenditure: Socio-Spatial Indicators of Affordability in Auckland ». Cities 38, p. 69‑83.

MEEM. 2016. Stratégie développement mobilité propre. Annexe de la programmation pluriannuelle de l’énergie. Ministère de l’Environnement, de l’Énergie et de la Mer.

Meissonnier, Joël. 2015. « L’accession à la propriété vient-elle rompre l’inertie des routines de mobilité quotidienne et permettre de s’engager sur la voie d’une mobilité durable ? Décryptage d’un paradoxe. » in Helga Jane Scarwell, Divya Leducq, Annette Groux (dir.), Transition énergétique, quelle dynamique de changement. Paris : L’Harmattan, p. 123‑132.

ONPE. 2014. Premier rapport de l’ONPE. Observatoire National de la Précarité Energétique.

Thomas, Marie-Paule. 2014. « Les choix résidentiels : une approche par les modes de vie », in Mobilités résidentielles, territoires et politiques publiques, Le regard sociologique. Villeneuve d’Ascq : Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

Vincent, Stéphanie. 2010. « Être ou ne pas être altermobile ? L’appropriation individuelle de pratiques alternatives à la voiture ». in L’action publique face à la mobilité, Logiques sociales. Paris : L’Harmattan.

1 For more information, see: https://www.cara.eu/fr/le-projet-cout-res/.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xBroadly speaking, residential mobility refers to a household’s change of residence within a life basin.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Maria Besselièvre (31 May 2022), « Accounting for Housing and Transportation Cost when private professionals are searching for a domestic property », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 05 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/new-voices/15596/accounting-housing-and-transportation-cost-when-private-professionals-are-searching-domestic