Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava explore the link between the development of a system linking megacities and rural villages and the railroad line, built 20 years ago, which connects the territory from Mumbai to the coastal region of Konkan. They analyze the age-old mobility of millions of Indian workers between the village and the metropolis, two places that are often distant and yet experienced as a single territory thanks to the physical but also family, community and religious ties that hold them together.

Images of hundreds and thousands of urban dwellers in Indian cities walking enormous stretches back to their villages – sometimes more than a thousand kilometers away - were flashed in the media all over the world during the pandemic in 2020. This happened for various reasons, but either way – they were relying on a phenomenon that was deep rooted and intrinsic to their lives – persistent circulatory movements between villages and cities

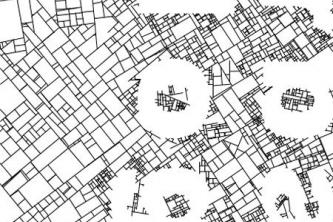

Millions of Indians live away from their ancestral regions and villages, while maintaining active links back home. The mass exodus from rural India does not end in hyper-dense centers but loops back to villages, which are transforming as rapidly as cities. There is a vast expanse of interconnected habitats that make up the sub-continent, in which primordial identities like community and family fuse with modern technologies like the railways to produce forms of urbanization that don’t conform to standard expectations.

This research project challenges the dominant model of urban development based on the growth of large cities fed by definitive rural emigration. It points out that railway lines in India have helped to create a circulatory model of urbanism which links villages, towns, and cities in a dense, reversible exchange network of people, goods, services and imaginaries. Trains remain highly affordable to the working classes who rely on them to make mobility a strong agent of transformation in their lives.

The aim of the research is to show the contours of such double-sided rural – urban movements facilitated mainly by the railways. This is important to assist in formulating policies that move beyond the city-country dichotomy and factor in rail mobility within the broader narrative of urban development in countries such as India.

This study followed earlier investigations on the theme, “Circulatory Urbanism: The Konkan Railways and Mumbai’s Urban System”, submitted to the Forum for Mobile Lives in 2013. It took these circulatory lives as its starting point to go into a detailed investigation of four families and one religious sect. They are all based in Mumbai with ancestral roots in the district of Ratnagiri on the Konkan coast, approximately 350 kilometres south of the city.

Building on the data base of the previous study, (involving 600 respondents on the Mumbai-Konkan beat), and re-confirming the widespread prevalence of double sided mobility and movement through secondary sources (studies on circular migration in India) it was evident that families and community organizations were the primary social infrastructure through which these movements took place. In the case of Ratnagiri – the movements took place over a century even without the presence of a railway network – which became fully operational only in the 90s. The railways have intensified the process and consolidated the relationship between the village and city even further.

The study employed ethnography as its primary methodology to produce accounts of four families and a religious sect – all of which had double connections with villages in the district of Ratnagiri and the city of Mumbai. This allowed our accounts to have a comparative framework between the older and younger members of the families as well which was crucial to our analysis.

Two families came from socio-economically marginal communities, called the Neo-Buddhist Dalits, who lived in a colonial mass housing project in the city keeping strong ancestral connections with their village in Ratnagiri. The other two families came from communities said to be ritually higher than the Dalits, but still marginal, and officially classified as “Other backward Classes”. They live in an officially notified slum in Bhandup, Mumbai and maintained active connections with their ancestral villages in Ratnagiri district as well.

The religious sect had followers from mixed-castes and had establishments in Mumbai as well as Ratnagiri.

The study was based on interviews with and visual documentation of different members of the family and sects at both places involving participatory techniques of data collection that involved collective travel to and fro and staying with families in the villages. The study produced detailed family histories as well as socio-economic profiles.

Our findings suggest that many families and social groups in the Konkan have structured their lives and livelihoods along the circular movements of their members. These movements create ‘fields’ or ‘territories’ that are at once rooted in specific locations and are floating above them - connected as they are to media, cultural, political and financial institutions and infrastructures. Transportation infrastructures and digital networks do not cause the movements – as historical analysis shows that they existed prior to modern systems – but they enable and accelerate them in tune with technologies of contemporary times. Users inhabit them and anticipate them in unexpected ways. Paying attention to their movements can help urbanists, policy-makers and industrialists in making strategic decisions.

The four families we followed all had life plans that expanded over a rural-urban spatial field, as well as an intergenerational temporal field. The older members, irrespective of the fact that they were born in their ancestral village or Mumbai, inevitably invested in their ancestral land, consolidating or rebuilding their houses. Some of them purchased additional land in the village, where they could build a new house that corresponded to their urban aspirations (impossible to achieve in Mumbai due to their financial status).

When making these choices, they always had their families in mind. No one in any of the families we followed pursued a purely individualistic project. Moving to the city meant getting closer to opportunities that would increase the welfare of their family, rather than the fulfilment of individualistic pursuits. Moving back to the village meant helping their parents or letting their children grow in a better environment. The younger generation were typically looking for live partners who belonged to the same community as them and who shared similar dual connections. The partners could be from the village or the city but had to belong to the same community.

The families’ investment in their ancestral villages contributed greatly to the overall development of the villages. Many villages shifted from building houses in mud, hay and bamboo to building in bricks and concrete. With the rise of ecological conscious- ness, we also observed that some people were going back to traditional materials, while innovating on the design.

No matter how long the families lived in Mumbai, the village remained a very active space encompassing several dimensions: it was an actual, physical place where one returned; a social network and safety net one could always rely upon; a cultural and spiritual field to which one belonged and provided a clear sense of identity; and it was a repository of memory that bound family members together. The village exists simultaneously in physical, virtual and mental states. These different states of the village are visited in different ways – by train or car; through screens and devices; and in thoughts and words. It remains present in the everyday life of the families we followed in more ways than one, existing beyond occasional visits. We could perhaps say that the village is a field rather than just a place, one that extends all the way to the city, and even merges with the city experientially, emotionally, socially and culturally.

Space is a dimension or grid in which things are located while place refers to a unique territorial location. Space can be more abstract and absorb the idea of relationships and bonds that can be expressed across geography through social imaginaries while places are particular points, locations, that are unique. In this sense, a home can be a socio-spatial dimension: spatial (for example, incorporating both city and village) and social (conjoined with a family or a community following the movements of the individual or group members, for which both places are homes). A place refers more precisely to the exact address of the house in the village or urban settlement.

Most of the respondents in the study spoke clearly of a sense of belonging that was attached to a family and community, connected to the identity of the ancestral village, but which spread across two places – the house in the village and the one in the city.

The circulatory regime between Ratnagiri and Mumbai emerged in every individual or familial journey and was located on two specific places, which were the two addresses, where people lived in – within the district or the metropolis.

While many of them spoke about the ancestral village as their “real” home, this was not borne out by the objective criteria of amount of time spent in both places – which was often fairly divided.

What was undeniable in nearly all the cases –was the socio-spatial convergence in terms of the family, the community, the relations ship networks and the way in which both places were seamlessly part of one world – in which the journey – whether annual or more often – always had an intensity that reinforced the bonds – of the people as well as to the locations.

India had conflicted rural-urban loyalties till the late 1980s. It refused both capitalism and conventional urbanization in the first half of its post-independence years and talked of primarily rural development even though cities continued to grow. Then it embraced twentieth century megacity urbanization from the latter half of the 1990s and is now attempting to transform, in one way or the other, the statistical 70% rural India into predominantly statistical urban population.

In reality, in many parts of the urban world, especially among nations from the African continent, South Asia and China, rural to urban migration does not spontaneously translate into a total relinquishing of village ties. Double-rootedness is very much a reality with families dividing themselves between the village or town of origin, and the big city.

Often considered an unstable arrangement, the phenomenon is commonly perceived to be transi-tory, merely a strategy for survival in an insecure urban context where investment in rural homes is seen as little more than self-financed old age social security. It is explained away as an inevitable but passing phenomenon that is part and parcel of traditional, rural nations transitioning towards development.

The findings of our study encourage urban planners and policymakers to imagine a city of arrival that is not an end point on a migratory path, but an edge from which the journey takes a new turn.

Policies and plans based on the notion that migratory flows are unidirectional, tend to freeze otherwise mobile populations. Understanding migration as a loop, rather than as a one-way street, may help us design cities and policies that could benefit the native place, the host city and the migrants them- selves.

a) We must look beyond city boundaries – and try creating inter-municipal and interstate mobility strategies to evolve administrative units that do not distinguish rural and urban sectors so sharply.

b) Consider the village as i) a neighbourhood in an interconnected national polity, and ii) as a valid habitat within a city.

c) Favour affordability over speed for public transportation systems, especially the railways in India.

d) Enhance connectivity between train stations and villages.

e) Recognize the multi-local nature of family’s income strategies.

g) Allow employees to follow seasonal rhythms and go back to the village for agricultural work during monsoons and harvesting.

h) Learn from informal labour arrangements: formalize “relay” labour arrangements, where people from the same family and village become part of the labour supply on a seasonal basis.

i) Rather than only focus on owning or renting homes, give importance to needs of accommodation as well that range from short term to long term strategies.

j) Encourage home-based economic activities and homegrown development both in villages and urban neighbourhoods. This encourages a large fabric of multi-sectoral activities across habitats.

k) Reduce the pressure on commuting with- in cities by encouraging more work-live conditions at every level. At the same time facilitate movement from city to the countryside.

l) Encourage cross-sector mobility (across primary, secondary and tertiary sectors).

m) Encourage personal investments in villages (for home and collective infrastructure).

n) Recognize the role of family, clan and community as facilitators for mobility, and motors of economic development.

Dowload the full report of this research

Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava, "Mumbay's Circulatory Urbanism", in Marc Angélil and Rainer Hehl, Empower! - Essays on the Political Economy + Political Ecology of Urban Form, vol. 3, 2014, Ruby Press, pp. 82 - 113

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xLifestyles

Policies

Theories

To cite this publication :

Rahul Srivastava et Matias Echanove (10 June 2013), « In the City and in the Village: The Circulatory Lives of Indians », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 10 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org./en/project/880/city-and-village-circulatory-lives-indians

Projects by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications