November 2013

The first part of our interview with Jean-Jacques Lebel showed us how mobility helps us to build our perspective, giving us access to the freedom and autonomy necessary for individuals to manage themselves. The second part of the interview addresses wandering and drifting from the standpoint of social and political emancipation.

Guillaume Logé : This idea of journeying and the use of hallucinogenic drugs remind me of the American artists of the 1950s who you knew so well. The Beat Generation marked the emergence of a new way of living and thinking, in reaction to social conventions, policies at home and abroad, mores, certain aspects of the art market, and so on. One of the founding works of this movement was On the Road . The novel, whose manuscript was mythically presented in the form of an immense scroll, - a road, seemingly without end - is the tale of a long journey. The main character is Neal Cassady, this “artist without works” [1] who so fascinated the members of the group. William S. Burroughs said of him “[T]his impulsivity, total and pointless, could reasonably be compared to the mass migrations of the Mayans…Neal is, of course, the soul of this expedition, which is pure movement, abstract and devoid of meaning. He is a wanderer by vocation, by nature.” [2]

Is the geographical wandering of the artists of the Beat Generation, both sublime and derisory, the goal in itself, a chosen way of life, or rather a quest, an impulse to…? What are these characters moving towards? Is wandering an escape from the forbidden, from a fossilized society? Or is it a quest for place - a kind of conquest of the West ( some West) that could be the setting for another possible life?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: It was all of that at once. Wandering is the ultimate philosophical experience; you don't know where you're going, but you leave, you move, you “have to go.” Someone who is afraid of wandering is someone who is already dead, frozen– a statue. Wandering is the very nature of life, the very essence of humanity. Physical wandering and mental wandering. And when my friends Ginsberg, Corso, Burroughs, Kerouac and the others went to Mexico, Tokyo, Benares, Tangiers, Paris (and they moved their whole lives), they were trying above all to get out of themselves , to cut the umbilical cord of the Puritanism of mainstream American culture— not only the Pentagon, with its war in Vietnam, Wall Street, General Motors, etc., but daily life itself, the weight of rampant capitalism that bureaucratizes everything, that militarizes everything and attempts to control everything (like today, via drones or permanent wiretapping).

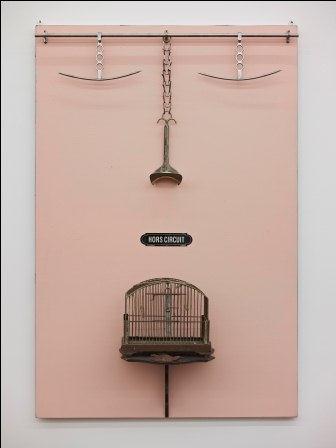

You've heard about the worldwide, large-scale telephone tapping scandal organized by the American and British secret services? Orwell predicted it. All of these things, they're attempts at Panopticon; to turn the entire world into a kind of prison, where all of our conversations and every move is controlled by a central power. Obviously, that's impossible to do, but that's what the Empire dreams of doing. It's Jeremy Bentham's fantasy on IT and digital overdrive. You just ban travel, thinking, art, revolution, you ban autonomy and keep everything under control. What's extraordinary is that Obama, Cameron, Putin and the Chinese are all trying to establish the same central power - by any means necessary. We are bombarded night and day by the “marvels of high tech,” even though what we need today more than ever is autonomy and to free ourselves from all the centralized powers that want to control and deny us - we, the people - the possibility of freedom of thought and action.

Thus are art, poetry and art-action more necessary than ever. Everything we’ve been trying to do since the 50s and 60s is even more indispensable today, because the systems of control have become much more sophisticated than they were back then. Real, concrete opportunities to travel freely and autonomously are much rarer nowadays, because if you have a cell phone and go to Cambodia or Mozambique, your whereabouts are known at any given moment. Google and the Pentagon have a common cause. Wikileaks, Bradley Manning, Julian Assange and Edward Snowden are absolutely right: in order to survive, we must resist and continue to exercise our freedom of movement, our freedom of spirit. PRISM, the global surveillance system, developed by the American government and denounced by Snowden, is a totalitarian, deadly device. We must thwart it.

Guillaume Logé: You also knew well another thinker and artist, who referred to wandering as dérive (drifting) — Guy Debord. The Bibliothèque Nationale de France recently dedicated an exhibition to him ( Guy Debord: Un art en guerre, March 27, 2013–July 13, 2013). Do you see any links between the wanderings of the artists of the Beat Generation and Debord's dérive , which ultimately is also a poetic experience, a way of combining art and existence?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: Not really links. Art and existence, yes, but it's really the fundamentals of living. I think there is a greater affinity between the Surrealists and the Situationists. It was André Breton and his friends who invented the concept of methodic dérive . They took the train, randomly got off in Blois, and set out on foot without knowing where they were going. This was the first time that had been done deliberately, with no specific goal. It's a famous story. They set out to discover. Then, the Situationists perfected the art in the city, going from bar to bar, drunk on various libations, encountering different people and situations and discovering places, without having planned anything ahead of time. This was a time in the 50s and 60s when a great many Americans vagabonded. There was a card called the Europass. The SNCF advertised it to students in the United States, informing them that for 300 dollars (I don't remember exactly how much it cost), you could get an all-access permanent pass good on any railway line in Europe. These Americans got off the plane - passes in their pockets - and took off wandering, destinations unknown. They discovered Europe that way, randomly. All my Americans friends had them. That's where the European dream started—a vast polyglot territory to explore by train, stopping wherever you wanted.

Guillaume Logé: And you,did you also practice this type of drifting?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: Of course. As soon as we had ten days vacation, we took an atlas, closed our eyes, and said “There” - and that's where we went. It's a way of discovering places off the beaten track. The problem with plotting a journey out is that it cancels the notion of journey. When you arrive in Angkor Vat, it's awful. The temples are sublime. It’s metaphysical architecture of indescribable beauty. But nowadays the crowds of tourists are so dense - thousands of people inching along like snails - that it becomes impossible to see anything at all. Tour operators impose this mandatory mass cretinism. It's not about seeing, but about saying you were there and taking some photos. Everything is pre-programmed. In Angkor Vat, there's a place where you have to have your picture taken. You don't even look at the temple. What counts is bringing back a photo. A perfect example of the tremendous alienation created by the cultural industry. Pseudo-travelers have to go there— like robots. But looking at a work of art or visiting an exhibition is like reading a book, and requires a considerable intellectual effort: you have to step outside of yourself to enter into the work. But tourists aren't there to work; they're there to make small talk: “Oh, it was an amazing exhibition…” It's a non-experience. Zero degree of mental experience. We have to completely revolutionize the idea of exhibition. It's better to go off on foot to discover some part of Paris, London, Nairobi or Santiago you don't know and to really do it - discover the people, have discussions and unnerving experiences - than to go to the other side of the Earth, see nothing and take away nothing that changes you as a human being. Alas, if you travel a lot - which is the case for me - you see that people move a lot physically , but remain mentally static. We must revisit the notion of “journey” with greater frankness and philosophical interest. Is not the word an exaggeration most of the time? I'm not talking about going from point A to point B. I'm talking about journey in the sense of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who walked from Chambéry to Venice. In Rêveries du promeneur solitaire, he talks about the things he thought about and experienced in the mountains, and the people he met. Some of his experiences were quite exciting. Read Montaigne's Voyage en Italie ; it's sublime. It's a high quality philosophical work. Every moment of his journey is a cognitive experience. I also love the travels of painters. Take Turner's trip to the Alps, for instance. It's a physical voyage but is above all a mental journey - the discovery (or rediscovery) of the self and of otherness. I like the works of Lafcadio Hearn, who traveled across Japan. They're lively tales with real philosophical intent. It's not simply moving to move, but moving to think , and thus deserves to be called a “journey.”

Guillaume Logé: You utilize technology and computers for certain works, like Les Avatars de Vénus . You just spoke of modes of traveling from a literary and artistic past, as part of the Grand Tour [3] or things like it. What are your thoughts on the means of travel currently offered by technology?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: The worst now are the CIA and Pentagon drones. It's a real disaster from a human point of view: soldiers kill people ten, fifteen thousand miles away— so-called enemies. But 90% of the time they miss and kill civilians. The order-givers are in Colorado, and the victims are somewhere in the mountains of Pakistan. It's monstrous. To kill one Taliban member they massacre twenty innocent villagers. The civilian populations are held hostage. That’s the logic of occupation by armies. Whether it's classic occupation (like during the Nazi occupation or during the war in Vietnam) or with high-tech drones, the result is the same: decimate the people by terrorizing them. And yet, one could imagine them being used to invent new ways of traveling mentally (as long as they're not armed drones), but more like the bathyscaphe, which was used to explore the ocean and examine things we never could never have imagined – except perhaps Jules Verne, who already imagined that there were 100,000 leagues under the sea. Then the bathyscaphe came along and, a century later, the drone. The drone is something of the same ilk, that could take us around the world in 80 hours, 80 days, 80 minutes or 80 seconds, I don't know, but not in a warlike, totalitarian way. Drones, like Google, photograph streets, houses, etc., with the intention to control, spy, and, alas, kill! Yet, there are extraordinary possibilities there - something to unearth, something along the lines of a psycho-geographical painting. We could produce works of art that would redefine the very notion of space-time. Basically, instead of being instruments of control, murder and imperialist domination, drones could be used as a tool for the creation and transmission of thought. But in order for that to happen, we must first do away with Empires.

Autres publications