November 2013

Interview with Jean-Jacques Lebel, a major artist and unrivalled actor and witness of some of the most important artistic movements of the second half of the 20th century. His work has an unusual relationship with mobility, addressing it simultaneously as a learning, creative and liberating process.

As always with Lebel, it is impossible to separate his work from the social and political dimensions that connect it to its epoch. How can we use travel to escape social coercion and forge our own capacity for self-reliance? Why does wandering make perspective possible? What kind of walking can shape thought and imagination? What uses can we make of mobility? What can we expect from it? How could it enhance our lives, if we, too, were to adopt an artistic approach?

Jean-Jacques Lebel is one the most important artists of our time. He was both an actor and a witness to some of the major artistic trends that marked the second half of the 20 th century, such as the Beat Generation, happenings and Surrealism. Among the friends with whom he exchanged ideas and/or collaborated were Marcel Duchamp, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Michael McClure, William Burroughs, Man Ray, Benjamin Péret, Henri Michaux, Octavio Paz, Edouard Glissant, Guy Debord, Félix Guattari, to name only a few. With Lebel, lists are often endless. An artistic genius, he is equally at home as a painter, poet, traveler, performer, activist, anarchist, collector, exhibition curator, festival organizer and, again, the list goes on.

We arranged to meet Jean-Jacques Lebel to hear him talk about wandering, so inextricably linked to his art - from the roving of the Beat Generation artists, to the dérive invented by his surrealist friends and systematized by Guy Debord. We went to meet him so that he could talk to us about his relationship with mobility without defining the term beforehand, and thus offering free rein to his own interpretation of it.

The work of Jean-Jacques Lebel is so abundant and significant from the point of view of art history and thought that we felt it important to include in this article certain remarks that may, at times, appear somewhat unrelated to the topic of mobility, but that are nonetheless essential for a more profound understanding.

Jean-Jacques Lebel gave us an interview on June 19 th 2013, with, as background, the exhibition that Geneva’s Mamco devoted to him, entitled Soulèvements II (echoing the exhibition Soulèvements organized by the Maison Rouge in Paris in 2009), as well as his creation based on an interview with Allen Ginsberg and a vast source of visual and audio documents on the Beat Generation artists, put on in four venues simultaneously, including the Centre Pompidou Metz. [1]

Guillaume Logé: You describe the creation Beat Generation/Allen Ginsberg that you’re presenting at the moment at the Centre Pompidou Metz and three other venues as “a virtual collage in motion, a roaming multimedia environment that is not linear but labyrinthine […],” and you speak of “offering visitors the chance to walk in and through a forest of images and texts.” In the terms you employ and as an art form that you’ve practiced a great deal, we find collage - this idea of traveling. This poetic mobility, here, seems to be intellectual and sensitive… and at the same time, you ask the visitor to travel physically. In your exhibition, you haven’t fixed the collage in a definitive manner, but rather have created the possibility of a collage, or collages in the plural, inviting visitors, so to speak, like at the happenings you used to organize, to make their own contribution to the work’s production. You created the conditions so that the (physical) wandering chosen by the visitor plays a role. What can you tell us about this meeting of movements, sensitive and physical, both individual and collective? For you, is the work the result of these mobilities?

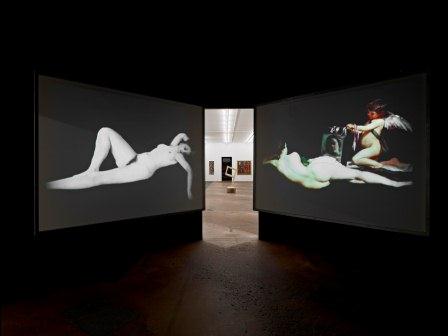

Jean-Jacques Lebel: It’s the reflection of an entire lifetime. I’ve had enough of hearing the incomplete quotation from Marcel Duchamp, “ It is the viewer that makes the painting. ” You hear it everywhere. It’s a cavalier excuse of the lazy, who plow into the void and sign it. For about forty years (and I remember having talked about it often with Duchamp himself), I have been suggesting that, rather than satisfying a consumerist, “ready-made culture,” we should be thinking about practices that invite the viewer to cooperate in the creation process. We haven’t given enough thought to what the work of looking is - the job of viewers. We shouldn’t infantilize them, ordering them to consume “ready-made” art, as happens in galleries and museums, where they are barely given the binary choice of pushing the “yes” button or the “no” button (Do you like this? Do you dislike this?). That’s not cooperation . It’s much more complex than that and involves a lot of work and effort, a kind of chiasmus. During happenings, we did a great deal of improvising, like in free jazz. These happenings took place through collective action. In my retrospective being shown at the MAMCO in Geneva at the moment- as was also the case with my exhibition at the Maison Rouge - a very large, open cube has been installed, made of four transparent screens. Onto them are projected four video segments of unequal lengths. It’s called Les Avatars de Vénus . Visitors are encouraged to step outside of themselves, and not to merely content themselves with being passive spectators, by wandering in and out o the cube. Depending on their line of vision, the view can include several screens, thus producing an infinite number of images through “multiple pileup,” or accumulation of the screens. By choosing to position themselves in one place or another and to move, viewers continue to deveelop the images. They reinvent and rearrange a work of art in perpetual motion, and take possession of it. In this way, the “author” is involved in what Guattari called a “collective arrangement of utterance” - a collectively-produced, open work.

Guillaume Logé: This work, Les Avatars de Vénus , seems to me to be crucial to your work as a whole, and allows us to approach and understand the connection between wandering (and I would add, ideally, wandering freely) and the possibility of a nascent regard. Could you tell us a bit more about the origins of this piece?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: Les Avatars de Vénus is the product of a very old dilemma - probably as old as painting itself - which has preoccupied me my entire life: with an image, whatever it may be, what is the image that came before and what is the image that will come after? What intellectual movement is this image part of? There are a few painters of genius who manage to suggest what came before and what will come next. I’m thinking of some of Titian’s or Giorgione’s Venuses, or certain works by Poussin. But it’s still a static picture, and I’ve always wanted to “kineticize” the static image and set it in motion. It was computer technology that ultimately allowed me to carry out this project. To begin - and for about forty years - during each of my travels, I started collecting (from stands, museums, the street, flea markets, libraries, everywhere), picking up and putting in big cardboard boxes images of what seemed to possess venustas , or rather one of the many forms of venustas . “ Vénusté ” is a word used by my friend Klossowski, but it’s from Ovid: what constitutes the venustas (charm or beauty) of Venus? What are the attributes that make her the goddess of love and beauty? There are as many interpretations as there are human beings, depending on culture, country, sex, age and so on. No two people will ever agree on what constitutes venustas , beauty or love. So I accumulated literally thousands of images, and then one day I organized them into thirty or so sequences. For example, there’s the prehistoric Venus of Willendorf; around her are natural, rounded stones that resemble her, gathered by people like André Breton and Roger Caillois, then, Jean Arp’s sculptures, then there’s the “Origins of the World” sequence, the Bettie Page sequence, etc. Once I’d organized these sequences, I asked two IT specialists, who worked for 7 years, to make the images of each sequence follow on from each another by constantly morphing into one another. We take two images, set up geometrical links between them, and create an anamorphosis through the connective combination of the two. The first image gradually becomes the second image, which becomes the next one, etc. You thus establish a movement which travels though and animates the images. The sculptures move, paintings and drawings move… The interesting thing, it seems to me, is that I have put an end to any kind of hierarchy between low and high art, styles, techniques and periods. It was the affinities that were important to me. If a Roman Venus were in a certain position and I found a drawing by Rodin or Otto Dix whose subject had the same posture, I created a connection, a continuity, a flow. All of it jumps across time and space. The important thing is not the timescale, but composing a sequence. And so you get Les Avatars de Vénus, where everything starts to move. You can wander inside and outside. You have a double point of entry – the meditative, immobile position, and the work of the viewer who, depending on their viewing perspective and the path they choose, sees different screens and therefore captures an accumulation of images that has not been pre-programmed. This was my first experience using computing as a tool to reinvent and energize the intellectual movement. For me, art should come as close as possible to how thought actually functions, thus to the subconscious, which is anything but static; hence the idea of transportation, not only amorous but artistic, musical or otherwise. The dictatorship of universal digitalization is trying to immobilize us, to nail us to the ground, and so we have to subvert it, overthrow it and sabotage it. As Nietzsche said, “You must have chaos within you to give birth to a dancing star.” And that’s my policy.

Guillaume Logé: The wandering that you encourage in viewers is part of the work of art itself. The spectator’s movement crosses with that of the work, whose images constantly appear in groups and simultaneities that are never identical. Wandering is a means of creating one’s own perspective and developing one’s thought.

Jean-Jacques Lebel: This comes from studying Nietzsche and his writing criticizing “a sedentary life.” [2] He writes that philosophers should walk, wander and move in order to think clearly. This is why he spent so much time walking in the mountains in Sils-Maria and around Genoa, for example. Ideas came to him as he walked in the mountains, in Caspar David Friedrich-type landscapes or along the Mediterranean coast. I’ve always followed Nietzsche’s advice to the letter. I’ve also thought a lot about people very different from Nietzsche, like Henry Miller, for instance, who talks about how he wrote his two very beautiful novels about Paris [3] while walking the streets of the capital. He used to set off in the mornings with a little notepad, and as he wandered he would invent, weaving together various events and eventually, by doing so, he constructed his tale. This practice is not, of course, exclusively Nietzsche's or Miller's; it belongs to a great many other artists as well. I believe that the intellectual work of someone who wants to be a “spectator” has to take place either walking or dancing. Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Young were great walkers. Thinking occurs whilst moving. There are also those who think as they drive - Kerouac and Guattari wrote while “on the road” [4] .

Guillaume Logé: You yourself have traveled a lot, living in the United States and organizing events in France and abroad. What’s your rapport with this wandering that you talk about? Do you share the same hunger for a poetic journey/experience? Has this influenced your own work, your way of creating, writing, compiling and collecting?

Jean-Jacques Lebel: Of course. Walking - whether it’s in the city, the countryside, on the beach or in the mountains - is something absolutely essential. Around 1953, when I was still a boarder at my high school in Meaux, we had a club with Raymond Hains, François Dufrène, Jean-Philippe Talbot and one or two others. Every Sunday, we would meet up at François’ house and had to invent something that in some way involved wandering, something that would surprise the others. Raymond Hains was fascinated by the big Swiss pocketknives in knife-makers’ shop windows - those giant red demonstration knives, with all the blades automatically opening and then, all of a sudden, closing again. He loved it! We’d cross Paris on foot and stop at different knife-makers’ shops. My contribution was to imagine an exhibition of odors. I'd take my friends and we’d go to Bercy, for example, where scrap-dealers would be welding with ozone: the smell of ozone – fantastic! Then we’d walk a few miles to get to Rue Vieille du Temple, to a shop that sold tea and roasted coffee beans. You could breathe in all sorts of teas and coffees, it was very refined. Each of us suggested a sensory experience to the four others. There was a lot of wandering. And what’s more, we got to explore Paris and all its nooks and crannies.

Wandering, once again, is what triggers it all. And random collage. Random collage in motion. It’s the notion of travel, but which tends to produce the conditions of the intellectual journey of a schize. I’m from the generation that experimented with mescaline and LSD, which ignorant people foolishly called trips, as in journeys. In 1965, a French journalist - a bit of a moron – who was interviewing Ginsberg and Corso asked Corso “Do you take drugs?” Corso replied, “Yes, but only Châteauneuf du Pape!” Our goal was “to get out of our minds.” In short, a Rimbaud-inspired “disruption of all the senses” as an experiment of absolute otherness and the “loss of the unity of the ego” that, in reality, is nothing but a monotheist fiction. How can we stimulate these journeys without ingesting hallucinogenic substances? Through works of art that encourage viewers’ cooperation and self-management, and by busing fantasies full of images that we provide them in such a way that they can make what they like of them and use them. To come back to my original point, “ It is the viewer that makes the painting ” or film, or music, or journey -but that implies a real effort on their part, a real intellectual and sensory contribution. Without that, nothing happens - they remain at a standstill.

[1] From May 31 st to January 5 th 2014 at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, from June 7 th to July 21 st 2013 at the Fresnoy – Studio National, Tourcoing, from June 15 th to September 1 st 2013 at the ZKM, Karlsruhe (Germany), and from May 31 st to September 1 st 2013 at the Champs Libres, Rennes

[2] For example, in Ecce Homo : “Remain seated as little as possible, put no trust in any thought that is not born in the open, to the accompaniment of free bodily motion – nor in one in which even the muscles do not celebrate a feast. All prejudices take their origin in the intestines. A sedentary life, as I have already said elsewhere, is the real sin against the Holy Spirit.” or in The Gay Science : “We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors — walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains.”

[3] Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn

[4] A reference to Kerouac’s celebrated novel On the Road

Autres publications