June 2013

The creation of the Industrial Heritage Trail provided a link between and coherence of the various constituents of the Ruhr territory. The trail is an integral part of the region’s founding identity, on which its conception was based. While intended as a tourist trail, it is also a trail that reflects the virtuous exchange between culture and economic and social development.

So, why do the works of the Mobile Lives Forum give so much importance to artistic expression? Is it simply for the purposes of illustration, or to argue the much more fundamental role of art?

It is above all an intellectual attitude and new practice that calls on art when we expect it to provide fruitful contributions from a societal perspective. If the challenge lies in understanding a deeper reality, in imagining new ways of approaching problems and solving them through innovative proposals, then there is everything to gain from learning to be a poet (in other words, breaking the boundaries between disciplines, making novel comparisons, questioning established ideas and changing our analytical standpoint); in short, by adopting the open, irreverent thought-laboratory which is that of the artist. This is what Arthur Rimbaud asks us to do when he speaks of breaking the shackles that limit our thinking and freeing ourselves from ourselves to attain “objective poetry” that liberates the real to reveal the invisible networks therein. The author of Bateau Ivre (Drunken Boat) - in the aftermath of the Paris Commune - examined the living and working conditions and political upheavals of his era in great depth, giving the modern poet the social role of “director of humanity” and urging him/her to become “a multiplier of progress!” [1]

Such an approach can be applied to any type of project, from the most micro to the most macro. The following example provides a practical illustration in the field of regional development – an example that is all the more interesting as the creation of a cultural tourist “trail” (that is really much more) lies at the heart of the project.

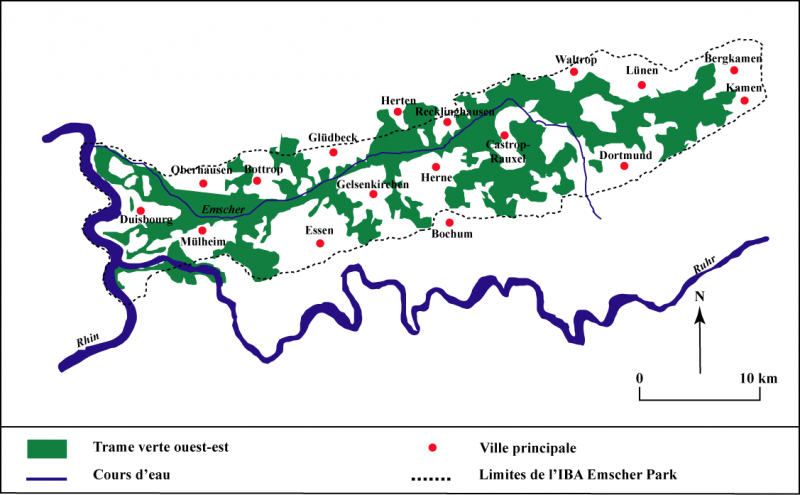

We’re talking about the IBA [2] Emscher Park program, which has become a reference. The first phase took place over ten years (1989-1999). Geographically, the project covers some 800 km² in the Ruhr region in Germany and, at the outset, involved twenty or so communities. In the 80s, this area was little more than a group of fragmented, rundown territories with obsolete and incoherent channels of communication. The goal: to reconfigure this stricken area from an economic, social and environmental standpoint.

To what extent can we learn from the attitude that led to the birth and management of IBA Emscher Park ? Can we, for instance, draw inspiration from it in thinking about mobility and how it pertains to local issues?

Let’s immediately highlight the fact that art played a major role in all of the phases of the IBA project. To begin with, it allowed the devastated region to create an identity and to reveal its hidden treasure. The designers of IBA Emscher Park , whose motto was “change without growth,” like to cite this Swedish proverb “Dig beneath your feet,” reminding us that, before looking for an outside solution, we must first look at ourselves. [3] This means a greater capacity to look and to see what others do not , thus behaving like an artist, poet [4] or “clairvoyant,” to use Arthur Rimbaud’s word. Let us likewise recall Paul Klee’s famous quote: “Art does not render the invisible, but renders visible.” [5]

Nobody imagined such a destiny for the broken Ruhr territory. No work, before that of Robert Smithson and his work on wastelands, or that of Albert Renger-Patzsch and Bernd and Hilla Becher on industrial sites, or that of John Tinguely on mechanics and movement were fully integrated, allowing IBA Emscher Park designers to understand that the Ruhr’s treasure was likewise its shame and the cause of its decline: the wastelands of its industrial past. Recognizing the esthetic value of the region’s many sites and giving them a heritage status, the territories connected to create the Industrial Heritage Trail. The Trail includes a number of notable sites, many of which - in addition to their architectural importance - host cultural events and installations by contemporary artists. Each year, tens of thousands of visitors visit the Trail, which has become - through the joining of extensive landscaped parks - the backbone of the region. Business incubators, schools, recreational centers and homes (rehabilitated working-class housing developments and neighborhoods in keeping with the context) are all part of it, as though a whole innovation process has been grafted onto a cultural/artistic heart, thus affirming the virtuous circle between art, culture, inspiration and all other societal dimensions.

The preliminary work done on the Ruhr’s identity is an aspect that is too frequently overlooked, as is the contribution of the "poetic" thinking that was involved. It is an approach that becomes richer with the many voices, perspectives and languages that add to it.

Thus functions the artistic creation that eludes established rules, preconceived ideas and clichés through a "seed of chaos," as Gilles Deleuze suggests for the painting of Francis Bacon [6] — a sort of Rimbaud-like "disturbance of all the senses" (sensitive senses and meanings).

Such an approach should be as open as possible. In terms of innovation, it could be closer to the open source model, which consists of submitting a proposed project for outside feedback (the best example being that of freeware). [7]

That is how the Ruhr’s population was invited to participate in the IBA - not only because the decisions were brought down to the local level, but because each community and its inhabitants were asked to share their archives, memorabilia and memories regarding this industrial past, which was fast becoming an emblem of the region. What better way to guarantee support for the project from the greatest number than to actively involve them? The method, while geared towards innovation, simultaneously created pride and strong rallying around the proposed changes. It is a method that seeks rather than imposing, drawing its wealth from the location’s specificities, context and population. We could see in this the model of the direct democracy that artist Joseph Beuys called for in order to reshape society [8] .

IBA Emscher Park combines the influences of architects and urban planners from different countries through its international call for tender, but also those of artists and the local population. The goal is not to create a recipe that can be applied in any circumstance, but rather to observe to what extent its process helped develop comprehensive responses to ecological issues, the housing crisis, waning economic dynamism and incoherent traffic networks.

So the relevance of fostering an active relationship with art perhaps is clearer now. The fundamental question of the purpose of art, says Joseph Beuys, "must be resolved in such a radical way that art can be seen as the starting point of any future production in all fields of work, and this concept of art must also be present in our minds if we are to succeed in reorganizing society." [9] Well beyond mere artistic intervention at a given location in a given territory, or contemplation of a given work, the goal is to develop a comprehensive artistic approach to reveal all possibilities with regard to an issue. By comprehensive we mean open, participatory poetic attitude that combines with the expertise gathered to consider the issue at hand.

Autres publications