June 2013

The study of the wanderings of children with autism carried out by Fernand Deligny’s network over the course of a decade opens up thinking about the determinants of travel, our ability to express our own mobility identity and the invisible at play in our relationship to space and to others. More broadly, it is mobility as an ontological expression that we are called upon to conceive.

I must begin by saying a few words about the life of Fernand Deligny (1913-1996) before plunging into the testing ground that his work opened up. The author of Vagabonds efficaces (among other works) devoted his life to children kept outside of our language – children with autism –, initially in institutions, and later as part of the support “network” he set up in the heart of the Cevennes. Educator, therapist, writer, essayist, artist, mentor, communist…while labels are reluctant to stick to Deligny, we nonetheless cite some of his different “roles,” only to better cast them off. Indeed, finding the words to define a man who was compelled to spend his entire life blazing new trails beyond and outside of language is a difficult feat. This is where he lived. This is where we intend to find him today — on the trails he left behind for us to do with as we so please.

For a number of years, the works of Fernand Deligny fell into relative obscurity due to numerous works going out of print, although exhibitions continued to expose certain works and films from his “network.” Such was the case for the inaugural exhibition of the Lam in Villeneuve d’Ascq in 2010, entitled Habiter poetiquement (living poetically), which devoted an entire room to the presentation of wander lines ( lignes d’erre )and the projection of the film Ce gamin, là . In 2007, Editions Arachnéen ( http://www.editions-arachneen.fr) began remedying this situation by publishing a 1845-page collection entitled Fernand Deligny, Œuvres , which assembles a large number of texts, analyses and documents. Two more exciting books have been added this year: Cartes et lignes d’erres, Traces du réseau de Fernand Deligny, 1969 – 1979 ( Maps and Wander Lines ) and Journal de Janmari .

Connecting through the mapping of movement

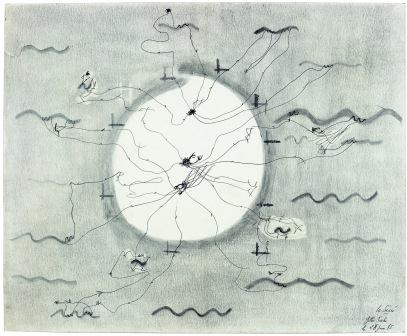

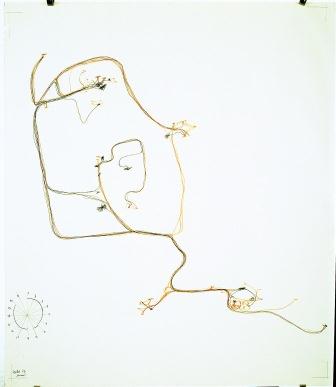

Our focus here is based on the surprising production of the drawn maps and “routes” used by the monitors of the Deligny network. Does how we label these documents really matter? In her introduction, Sandra Alvarez de Toledo says “[d]espite their visual appeal, these transcriptions resist the label of ‘works of art’ – brut or conceptual.” [1] It is not certain that Dubuffet, on the other hand, would have been so reluctant to liken them a form of art brut. These wander lines – made by “the common man” [2] – seem the perfect illustration of Nicolas Bourriaud’s definition of art: “Art is an activity that consists of producing relationships to the world using signs, shapes, gestures and objects.” [3] From both an esthetic point of view and their ability to “render visible” (in the words of Paul Klee [4] ), to create emotions and thoughts, to show what others do not see, their place in The History of Art seems obvious, and likewise explains their inclusion in the Cartes et figures de la terre exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 1980 and the Habiter poétiquement exhibition at the Lam in 2010.

These wander lineswere largely drawn over a decade, starting in the mid-60s up and until the mid-70s. Jacques Lin, a “ présence proche” (close presence) and fellow traveler who worked with the children, one day expressed his frustration at seeing the latter banging their heads against rocks and his chagrin at not being able to connect with them through language. Ferdinand Deligny advised him to draw lines, to initiate an approach not through language - which these children did not have - but through their patterns of movement.

Deligny proposes to stop “looking with words,” as we constantly do with respect to our “kind,” waiting for them at the crossroads of our interpretations and our linguistic intentions, to instead “follow them with lines,” to follow their trails, discover where their world is, which is in(visibly) not ours…Hence this surprising undertaking of building a unique country (the exact opposite of a utopia) in which, gradually, as in a slow dance, it becomes a question of superimposing without ever confusing these two territories, these two worlds of paths, ours made of words, theirs made of existence, and whose maps - the plotting of wander lines - are testimony. Not to bring them where we want them to be (to educate them or heal them) but rather to go to where they are in order to seek a shared experience, in the full sense of the word “shared.” [5]

The expression of existence is manifested through wanderings and the plotting of these wanderings. And so the intense task of producing background maps (topographies of the areas of residence called “ aires de séjour ”) and the layers to superimpose on them (plotting the children’s wander lines) began, and was subsequently carried out by each présence proche . Regular meetings gave rise to discussions and allowed Deligny to share his thoughts.

Wander: the word came to me. It says a bit about everything, like all words. It ranges ‘a way of moving forward, of walking,’ says the dictionary, to ‘the acquired speed of a ship whose motor has been cut,’ and also the ‘tracks of an animal.’ A very rich word, as we can see, that speaks of walking, the sea and animals and likewise has other echoes: ‘to wander: to deviate from the truth; to go from one side to the other, randomly, on an adventure.’ Jean-Jacques Rousseau says ‘to travel for travel’s sake is to wander, to be a vagabond.’ It is also ‘to occur here and there fleetingly, on various objects, with a smile.’ [6]

Movement as lines : a revelation

Wander. Deligny needed a term with broad meaning, with an echo of séjour, orsojourn. The movement takes place around a given aire de séjour , with its landmarks linked to everyday activities, its rituals repeated day after day. Sometimes a more fundamental change of place, as the result of a ‘transhumance’(gathering, on foot, at another of the network’s aire de séjour , often in the company of a herd of animals), enables the expression of new behaviors as regards movement.

“Twenty miles that day, from the old place to the new one, through the weathered waves of the Hercynian chain…The children can’t believe it, [and are] puzzled by this journey today that does not end at or return to the typical place.” [7]

… now we just have to see what comes out in this completely new place, to give rise to new initiatives again…This is what we called the search for N. The capital [N] doesn’t mean “North.” It is Nous [Us] , but not us in person: it isn’t a guy, or a woman for that matter. It’s something else, [this] N. As there is a geography of the body, there will be an identifiable geography of the human space.” [8]

The series of drawings bear witness to the “thousand and one paths taken and retaken” [9] in this “identifiable geography of human space.” The trajectories of the adults combine with those of the children. The “intention” behind the adults’ movements seems clear: getting water, wood, etc. A purpose that is immediately accessible and understandable for us is associated with their lines, while those of the children are meandering and spin around.

“ That child

spins around NOTHING

on nothing

desperately

lost

so was he looking for it, this self

that he was seeking? ” [10]

What is contained in this “NOTHING” that nonetheless dictates movement? We mustn’t exclude the nothingness. Deligny contemplated it, but did not stop there. Language stumbles once more. Via these tracks, we follow trails within a space of non-language. Only strokes. Lines. The beginning. The movement expressed. It expresses for expression’s sake. The journey foreseen as a mode of communication – a voice – albeit hermetic.

“…communication, in addition to establishing relationships, is also what we communicate, the medium and the message; and also the passage from one place to another; the door and road are communication; to no longer be able to distinguish end and means; if communication is the road, then it is journeys; if it is voice, it’s language…Which means that meanderings of action are merely detours of speech. ” [11]

An eternal return to the question of language via these wanderings. This is not to say that these children want to communicate, explains Deligny, but that their movement communicates. Wander lines explore the link between Action (walking and the gestures that accompany it) and speech — existential speech reminiscent of that of the poet, founding speech, the speech examined by Heidegger that creates being there in the world ( Dasein ).

Language is not a free tool; quite the contrary, it is this coming into view (Ereignis) that itself has the ultimate power of determining a man’s being. ” [12]

In his own words, Deligny writes:

“Drawing [wander lines] is a trace of being, if we understand that this ‘being there’ is not that; it is being and not the being, and charting thus represents nothing.” [13]

What governs individuals’ mobility ?

The markings on the maps challenge our sense of movement and our rational approach, as though there were some kind of gratuitousness in the swervings of these children which clashes with the purposeful prevalence of movement in moderns societies. Are we not accustomed to movement based on economic efficiency: saving time/not wasting it/maximizing it — as we manage money? The law of financial return applied to mobility. Movement for movement’s sake is rare, even in the sphere of vacations and leisure, where performance and time management still often come into play.

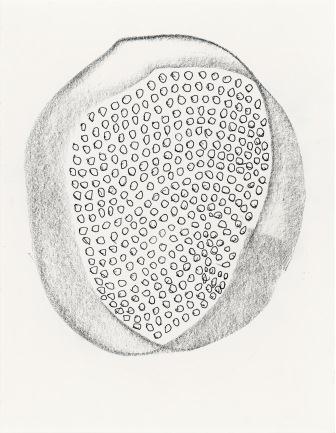

But can we speak confidently of freedom when talking about wander lines and their meanderings? Maybe. Unless it’s not so simple. Or should we say that these children simply move according to who they are, based on an intimate relationship (intimacy - sui generis – that is unique to each person) with space? Their wanderings reflect a relationship — a relationship with this invisible that Deligny does not name (in any case, is it possible? or necessary?). Some suggest the effects of emotions, or the influence of energies (Deligny notes how the children are attracted to water. Janmari even discovered hidden springs). Let us keep in mind this image of the diviner. It is interesting in this regard to relate what Deligny said about Australian Aboriginal painting in his essay “L’Arachnéen” to the drawings that Janmari, one of the children, made in his journal.

[on the gestures of Aboriginal painters]: “… with a movement of the hand that reiterates the journeys, that go back and forth where the hand must go; this hand is not his own: it is a hand he uses like he uses the little stick that has been chewed at one end as a paintbrush: it is the human that is at work. [14]

We may extrapolate on a simple identity of form, but the small circles Janmari amasses page after page bear a striking resemblance to the water holes depicted by Aboriginal artists, who are also enthusiasts of pattern repetition. Remember that Aboriginal painting is principally a topographical representation—that of the mythical Dream Time. The drawing of places - in lines and points - all show the movement of the ancestors who modeled the continent’s land, and who continue to dictate its organization via the artists connected with them.

Should we see evidence of the ability to divine in this relationship with water? This would mean adding to the drawings on the background maps, in addition to visible representations of the environment, all in relief.

“The world in which we live is a living world, where each thing and each creature evolves in an infinite, uninterrupted flow of energy. ” [15]

In any case, that would be one way of trying to get a little closer to these movements that, indeed, defy language, the latter being at this point confined either to substance or abstraction, which hardly accounts for the full depth of the reality. We especially sense this depth at places where several wander lines intersect. Deligny calls these points “intersections.”

“Of intersections one could say that it is the cause of what escapes us that escapes us. For example, the attraction to water is very common in autistic children. Similarly, the fact that they stop and rock at a fork in the road is a common fact of wander lines. The term trimmer therefore simply means the fact that there is something that attracts a number of wander lines. [16]

Something that attracts. The parallel with the image of the diviner, whose movement is dictated by the presence of water, at the meeting of springs, is astounding. Is it intuition of an invisible of this kind that Deligny’s argument points to? Or should we instead consider it in terms of a much more abstract reality, or as a purely psychological phenomenon that eludes us?

Drawing that lets us see… the person who does it – draws - still needs to be prepared to willingly see something more than what his eyes show him. [17]

What we can say is that wander lines reveal something above and beyond the gaze. The patterns of movement are an expression of a beyond that is in no way mystical; on the contrary, it’s a beyond grounded in reality (under the first layer of reality) that we speak of. Journeying expresses something beyond words, beyond the gaze. Journeying thus expresses beyond the senses.

Once again, the analysis joins the ontology. Could Deligny’s approach be compared to that of Nietzsche, who relied on poetry after finding it impossible to make philosophy using words (thus followed the composition of Thus Spoke Zarathrustra) ? For Deligny, this impossibility was true for both language and action. “Modes of journeying” would be a useful term for approaching a new philosophy.

by dint of drawing

wander lines

from each child there

we get to see a little of that which does not concern us

I mean that our blind regard of speech

has trouble seeing

us

it pushed him like a body

drawn in gray

almost as black as the water

by dint of being there no doubt

and going and coming [18]

From determinants of mobility to the development of an emancipatory mobility identity

Deligny’s lifework questions our ability to develop our own way of moving, to move based on ourselves - what we are, what we feel, our relationship to space - and not on how we have learned to move, obeying outside rules that we have gradually integrated. In her preface, Sandra Alvarez de Toledo talks about the relationship of the maps in Deligny’s network as an “experiment in deprogramming.” [19]

How much freedom and how much of ourselves decide our mobility? The contemplation of wander lines invites us to reflect on the laws that organize our modes of travel, to reflect on their origin, on what is mandated by a form of social and economic organization. Regaining control over how we move around is to create a link to what we are — a stronger link between what makes us and reality. It is to open up our senses, to make room for an elaborate web of intuitions and sensibilities that we are quite unused to allowing to take over. We are called to become diviners (to continue with the parallel between Janmari and water); in other words, to expand our perception, abilities and specificities of our being: to develop our own mobility identity. In the Cahiers de l’immuable , Deligny writes:

Diviner, this social innovator? Why not? Diviner, anybody who is, who practices perceiving the vibrations that tickle the soles of their feet and their spines and reaching the hands – or words? – while whatever he could be thinking (about it) remains on hold. [20]

The art of plotting, developed by Deligny, has a double movement, both towards the other and towards the self. Wandering is, for me, the expression of the other’s being — a point of contact with the existence of the other, the place of birth and of propagation of my being’s essence.

“What is to transcribe, it is [our essence] as much as possible.” [21]

Approaching Deligny requires accepting a radical reexamination. Only through such an effort can horizons open.

That’s what I mean about maps and their history. Born of Jacques’ anxiety over responding to the kids’ parents, they were subverted: an instrument of neither observation nor interpretation. Subverted toward the disconcerting. It’s your attention to the disconcerting, being available to that which breaks routines and discipline, that is the very definition of the network’s libertarian stance. [22]

In short, Deligny does away with the usual, comfortable analytical tools (i.e. observation and interpretation) and instead proposes we disconcert ourselves. Wander lines are first an invitation to “break” the analytical frameworks, ready-made conceptions and blanket terms. The fluidity of wander lines is the affirmation of a seizure of power by a man freed from all societal determinism. Wanderings – obeying only the individual in his/her essence and his/her relationship to the environment, and nothing else – mark a kind of fullness of being, where the complete reappropriation of movement by the individual is the first requirement for him or her to question and challenge the entire linguistic edification and the logic structures that organize our thinking, representations and social organization. Wander lines, movement, are birth and empowerment.

Wander lines? Are they paths? With carefully traced paths, we will come back. Right now, they are life rafts, [23] three maps escorting an event: the transhumance of the herd…When the wander line manages to DO, it would seem, thanks to use, to its handling, to the handling of drift, the ink line wants to brush up against it. Thus, wander lines are not – when maps are rafts – transcribed journeys, traces. They are ways of being in the search for that which, coming from us, allows. [24]

Autres publications