April 2013

The exhibition “Adrian Paci: Vies en transit,” (Paris, February 26-May 12, 2013, organized by Jeu de Paume) offers original perspectives on many aspects of mobility.

For the first time, a retrospective of Albanian artist Adrian Paci’s work has been organized in France. The title of this exhibition of videos, paintings, sculptures, photographs and mosaics is Vies en transit (lives in transit). I would like to put the reading of this exhibition in the perspective of the “Mobility as capital” debate published on the Mobile Lives Forum website.

It is quite justly that the curators of the exhibition, and the authors of the interesting catalogue that accompanies it, use the idea of transit and transition to bring together the diverse explorations of Adrian Paci. Mirroring the course of his own exiled existence (Paci left Albania with his family in 1997 to settle in Italy), the artist decrypts moments of bonding and disconnect in individuals’ lives. Intimacy and identity are linked to geographical, social and family displacement (think in terms of the societal, economic, political and sociological determinism that weigh on man today).

Before offering any analysis, I would like to stress the esthetics and poetry of these works, which one could choose to address from solely a sensitive point of view. The videos demonstrate stunning mastery of framing, editing, slows, blurs and tones of shadows and color, wherein one recognizes the hand of the painter Adrian Paci at the beginning of his career (and continues to be in works that show great sensitive strength, borrowing from the cinema a narrative approach and polytypic arrangements reminiscent of storyboards. The use of mosaic sometimes breaks free of the rigidity of the medium, spilling over into videos like The Last Gestures (2009), whose composition and somewhat pixilated images recall both the appearance and the religious symbolism of this medium.

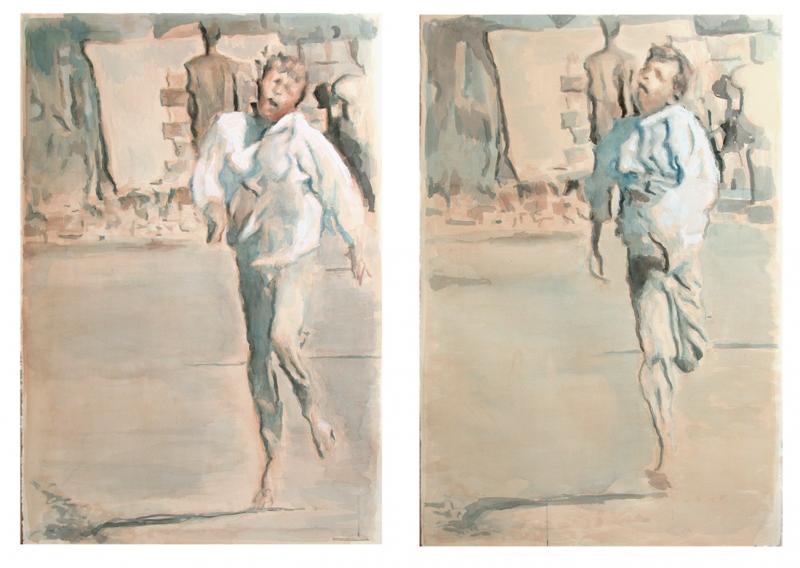

In 2001, Adrian Paci earned a strong reputation in the art world with his work Home to Go , whose plaster figure carries an upside down roof on his back. To what place do we belong? Where is our home and what does it look like (our “being there” [1])? And what if man were doomed to perpetual wandering?

To cite the artist, “Home, as I said, is not only a house, a roof, and a family; it is also a state of stability, connection, affection, and identification with something. For me, coming home does not address the question of emigration, but rather the larger question of the quest for stability lost. In a context of substantive transformation and change, we must create strategies of survival and continuity, and the idea of coming home is part of that” [2]. This means developing survival strategies to cope with new forms of imposed mobility that break up the home and cause humans to lose their inner stability.

This question of a mobility that challenges individuals’ very existence is present in many works. Centro di Permanenza Temporanea [provisional detention center] (2007) shows us a procession of passengers on an airport tarmac moving towards a gangway, crowding on a platform and stairs, and, in the absence of an aircraft, continuing to wait, frozen in interrupted mobility that rejects them and at the same time makes them prisoners. They certainly do not belong to the “kinetic elite” described by Tim Cresswell [3].Their procession makes us think more of candidates for emigration who have been brought back to a border that, in this case, has closed behind them, rendering them statelessness inhabitants of non-places [4]. And the airport becomes a non-place – the same non-place for these prisoners of the planet’s political and economic upheavals as for the hyper-mobile taking off and landing from their gangway prison.

The video opens with highly-composed, wide shots that show the empty tarmac, and then the arrival of the strange file of visitors. It continues with wide shots that linger on facial expressions, constantly moving back and forth between the individual and the universal and the impact of accelerated globalization on the former (a crosscutting theme in Paci’s work). In his way, the artist carries out Walter Benjamin’s desire for a cinema stripped of all airs, one that succeeds in showing the inner workings of the domination that weighs on individuals [5] (in this case, the domination of political and capitalist systems that generates phenomena of exclusion, relegating these individuals to non-places by the incessant flows in which they are doomed to remain strangers to themselves and to the world, as Home to Go seems to tell us. The authors of the catalog cite Zygmunt Bauman’s essay “Liquid Modernity” in which he says, “the sedentary majority is governed by a nomadic, extraterritorial elite…[t]he people who move and act faster, those who come closest to the instantaneity of the moment today, are those who lead. And those who cannot move as fast and in a visible way…those who cannot change places at will, are led…[t]he contemporary struggle for power has been waged between forces equipped respectively with arms of acceleration and those of procrastination” [6].

All of these ideas can be found in the superb video The Column (2013), filmed on the occasion of the exhibition. The work shows the journey of a block of marble from its extraction from a quarry in China to its shipping, during which sculptors transform it into a Roman column. The block of marble is loaded on board a kind of factory-ship, a cargo whose open hold serves as a workshop for the sculptors. Capitalist logic perfectly carried out; in order to maximize shipping time, the work is completed during the journey. Shipping - once economically unproductive – has become a productive power. Could this be a (desirable) solution to Thomas Birtchnell’s analysis that “cargo is becoming less and less profitable”?

If one accepts the idea that these workers are in fact hyper-mobile, it is surely not in the sense described by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello (and cited by Vincent Kaufmann and Hanja Maksim). In this case, capitalism does not require employees to be mobile in order to bounce from one opportunity to another. They are not being asked to be flexible and adaptable. On the contrary, if we adhere to the authors’ analytical framework, one can even go so far as to question their very mobility. How great is their ability to move in different mental worlds? Or geographically? Here, mobility is not a factor in career advancement. It does not result in any potential for change in their social position. These men have no particular mobility skills, or - t o use Vincent Kaufmann and Hanja Maksim’s term - no motility capital. They have the same skills as any other stonemason; the only difference is the decision to make them work in a floating workshop rather than a stationary one somewhere in China. They are not consultants going abroad for an expert mission. They are workers working on a block of marble that weighs several tons. The movement that we witness is that of the least mobile work imaginable, and the mobility is not that of the sculptors, but rather that of their tool of production (thus not human mobility but mobility of the material to which man is attached). These workers belong to a class of mobile-immobiles (or sedentary mobiles), who are exploited by the mobile leaders of modern capitalism.

Although they are in motion , it is questionable whether these sculptors really move. Do they not seem more like prisoners, thrown into the hold, surrounded by walls that obscure the landscape, their only view that of the implacable blue sky above them? In fact, they are cut off from all geography; they could be anywhere and it wouldn’t change anything. The factory-ship that makes the journey “productive” is like a floating prison. And what of the individuals caught in this system? Their faces, whitened by marble dust, like so many masks questioning the fate of identity, with no dialogue to give us a clue. The only voice is that of the constant hum of the machines.

This video of this boat trip presents us with a paradox. Instead of true mobility, what these workers have accepted is isolation and confinement. Their capital is not mobility capital, but confinement capital (anti-mobility capital?).

The workers in this film seem to give credence to the ideas of Simon Borja, Guillaume Courty and Thierry Ramadier: “By being mobile, people do not capitalize, they simply comply with orders and - the great paradox - in most cases remain in the social, economic, and spatial place that was theirs to begin with.”

Mobility is seen here as a form of capitalist domination. We are told that in the development of our societies as it is taking place, one needs substantial mobility capital to be accepted by the system and to get a job. Talk about mobility capital as regards this particular work, one must replace this term with “confinement capital” or “imbalance and uprooting capital.” These individuals are not so much asked to move as to be able to live in non-places (i.e. the boat) in which their very inner self are challenged.

[1] See Heidegger’s Dasein which comments on poetic dwelling of the world of Hölderlin. HEIDEGGER Martin, Approche de Hölderlin , Gallimard, 1962

[2] Text by Adrian Paci, in Adrian Paci, Transit , catalog for the Vies en transit exhibition, Jeu de Paume, 2013. Coedited by Jeu de Paume, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Mousse Publishing, Milan, p.34

[3] CRESSWELL Tim, On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World , London, Routledge, 2006

[4] See AUGÉ Marc, Non-lieux: introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité , Paris, Seuil, 1992

[5] See BENJAMIN Walter, A Short History of Photography and The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

[6] BAUMAN Zygmunt, Liquid Modernity , Cambridge Polity Press, 2000, p.119

Les recherches sur la transition s'intéressent aux processus de modification radicale et structurelle, engagés sur le long terme, qui aboutissent à une plus grande durabilité de la production et de la consommation. Ces recherches impliquent différentes approches conceptuelles et de nombreux participants issus d'une grande variété de disciplines.

En savoir plus xLes mesures de confinement instaurées en 2020 dans le cadre de la crise du Covid-19, variables selon les pays, prennent la forme d’une restriction majeure de la liberté de se déplacer durant un temps donné. Présenté comme une solution à l’expansion de la pandémie, le confinement touche tant les déplacements locaux qu’interrégionaux et internationaux. En transformant la spatio-temporalité des modes de vie, il a d’une part accéléré toute une série de tendances d’évolutions préexistantes, comme la croissance du télétravail et des téléachats ou la croissance de la marche et de l’utilisation du vélo, et d’autre part provoqué une rupture nette dans les mobilités de longue distance. L’expérience ambivalente du confinement ouvre sur une transformation possible des modes de vie pour le futur.

En savoir plus xAutres publications